I know that there is always music to be found in Jerez de la Frontera. Usually it’s of the flamenco variety, but I have, in the past, happened across 13th century song cycles, jazz, classical, modern tribute bands (hearing ‘Radio Gaga’ resounding from the walls of the ancient Alcazar some years ago was quite something) and world music. This summer is no exception with a range of concerts, sometimes free, sometimes charged for, in some spectacular locations. July saw ‘Baile’ a series of flamenco dance performances in the 13th century Claustros de Santo Domingo and ‘Mima’ or Musicas Improvisadas En El Museo Arquelogico in the eponymous museum. I caught the wonderful jazz trio Nocturno on a sultry Wednesday night playing their own compositions, inspired by the night and Frankenstein. The music was stupendous. I wondered what Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley would have made

I know that there is always music to be found in Jerez de la Frontera. Usually it’s of the flamenco variety, but I have, in the past, happened across 13th century song cycles, jazz, classical, modern tribute bands (hearing ‘Radio Gaga’ resounding from the walls of the ancient Alcazar some years ago was quite something) and world music. This summer is no exception with a range of concerts, sometimes free, sometimes charged for, in some spectacular locations. July saw ‘Baile’ a series of flamenco dance performances in the 13th century Claustros de Santo Domingo and ‘Mima’ or Musicas Improvisadas En El Museo Arquelogico in the eponymous museum. I caught the wonderful jazz trio Nocturno on a sultry Wednesday night playing their own compositions, inspired by the night and Frankenstein. The music was stupendous. I wondered what Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley would have made of it, I’d like to think that, free thinker as she was, she would have enjoyed it as much as the audience did. Afterwards, given the temperature, musicians and audience spent the next hour or so in the Plaza Mercado (the old Moorish market place, which features in my novel Reconquista ) drinking excellent wine.

of it, I’d like to think that, free thinker as she was, she would have enjoyed it as much as the audience did. Afterwards, given the temperature, musicians and audience spent the next hour or so in the Plaza Mercado (the old Moorish market place, which features in my novel Reconquista ) drinking excellent wine.

Two other series continue into August – ‘Viernes Flamenco’, with some tremendous musicians, David Carpio and Manuel Valencia to name but two, again in the Claustros and ‘Noches de Bohemia’, likewise. I was annoyed to have missed the sublime-voiced David Lagos in the latter, but I did catch the Raul Rodriguez Trio with special guest kora player, Sirifo Kouyate. On Saturday evening the set included music  part-flamenco-part-arabian (you could say the first comes from the second anyway), modern rock-style electric guitar and the wonderfully fluid arpeggios of the kora. These concerts run into the 55th Fiesta de la Buleria de Jerez, a stunning series of gala concerts with the cream of flamenco performers – Manuel Lignan, Gema Moneo, David Carpio, Antonio El Pipa, Manuela Carrasco and more. The buleria was invented in Jerez, it is very rapid and complex, with demanding changes in rhythm for all performers. Guitarists consider it possibly the most virtuosic of the soleas. Lively and intense, it is also great fun, often performed at parties and as a dance at the end of a show, when all the performers (not just the dancers) join in. With origins in the nineteenth century it was popularised outside of Jerez and other corners of Andalucia in the twentieth century by ‘cross-over’ artists like the guitarist Paco de Lucia and singer Camaron. Still going strong, it is celebrated annually in Jerez, just before the beginning of the vendimia, the wine harvest. This, and the other series of concerts have been augmented by free concerts and dance performances in Plaza Ascuncion, in front of the 13th century church of San Dionysio and the neo-classical town hall.

part-flamenco-part-arabian (you could say the first comes from the second anyway), modern rock-style electric guitar and the wonderfully fluid arpeggios of the kora. These concerts run into the 55th Fiesta de la Buleria de Jerez, a stunning series of gala concerts with the cream of flamenco performers – Manuel Lignan, Gema Moneo, David Carpio, Antonio El Pipa, Manuela Carrasco and more. The buleria was invented in Jerez, it is very rapid and complex, with demanding changes in rhythm for all performers. Guitarists consider it possibly the most virtuosic of the soleas. Lively and intense, it is also great fun, often performed at parties and as a dance at the end of a show, when all the performers (not just the dancers) join in. With origins in the nineteenth century it was popularised outside of Jerez and other corners of Andalucia in the twentieth century by ‘cross-over’ artists like the guitarist Paco de Lucia and singer Camaron. Still going strong, it is celebrated annually in Jerez, just before the beginning of the vendimia, the wine harvest. This, and the other series of concerts have been augmented by free concerts and dance performances in Plaza Ascuncion, in front of the 13th century church of San Dionysio and the neo-classical town hall.

Then, of course, from September there is the Autumn programme at the Teatro Villamarta. No matter what time of year song, dance and melodies are always to be found in Jerez, city of music. Here is a snatch of a buleria played by a master… watch those fingers.

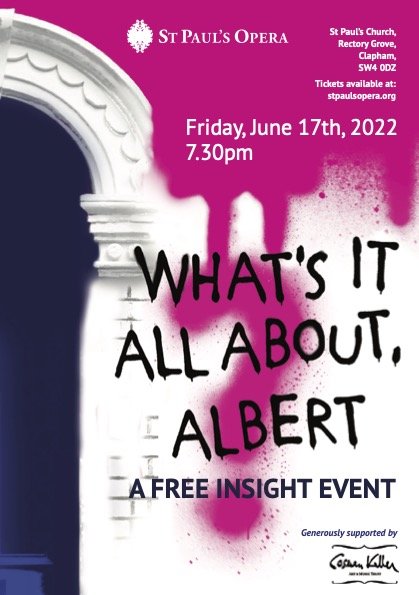

the May Queen. But there’s not a virtuous maid to be found. Shock, horror! Too many have erred ( being seen ‘out after dusk’, or ‘wearing short skirts’ ). So a King of the May is preferred, the virtuous (and virginal) Albert Herring.

the May Queen. But there’s not a virtuous maid to be found. Shock, horror! Too many have erred ( being seen ‘out after dusk’, or ‘wearing short skirts’ ). So a King of the May is preferred, the virtuous (and virginal) Albert Herring. We filed inside, carrying cushions ( those pews can be unforgiving to the rear end ) to find the colour scheme continued. The musical director and conductor, Panaretos Kyriadzidis took up his position, with pianist Francesca Lauri and the story began. Florence Pike (mezzo, Natasha Elliott), housekeeper to Lady Billows (soprano, Charlotte Brosnan) was preparing milady’s parlour for the meeting of the May Day committee – Miss Wordsworth (soprano, Anna Marmion), mayor Mr Gedge (baritone, Adam Brown), vicar Upfold (tenor, Peder Holterman) and Superintendent Budd (bass, Masimba Ushe) to choose the May Queen.

We filed inside, carrying cushions ( those pews can be unforgiving to the rear end ) to find the colour scheme continued. The musical director and conductor, Panaretos Kyriadzidis took up his position, with pianist Francesca Lauri and the story began. Florence Pike (mezzo, Natasha Elliott), housekeeper to Lady Billows (soprano, Charlotte Brosnan) was preparing milady’s parlour for the meeting of the May Day committee – Miss Wordsworth (soprano, Anna Marmion), mayor Mr Gedge (baritone, Adam Brown), vicar Upfold (tenor, Peder Holterman) and Superintendent Budd (bass, Masimba Ushe) to choose the May Queen. sensible, if ponderous and all defer to milady, who is ‘overbearingly enthusiastic’ (as described by Britten and his librettist, Eric Crozier). Yet Albert (tenor, Hugh Benson) is decided not upper class, being the greengrocer’s son and neither are his friends, Sid, the butcher’s boy (baritone, Alfred Mitchell) and Nancy, his girlfriend (mezzo, Megan Baker). One of the delights of this opera is the demotic, everyday language which Britten insisted upon. It is used well and wittily – after his night of debauchery which the May King prize money affords him, Albert thanks the shocked villagers ‘And I’d like to thank you all, for giving me the wherewithal.’

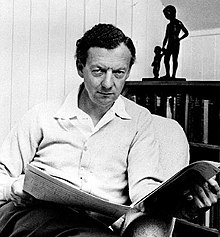

sensible, if ponderous and all defer to milady, who is ‘overbearingly enthusiastic’ (as described by Britten and his librettist, Eric Crozier). Yet Albert (tenor, Hugh Benson) is decided not upper class, being the greengrocer’s son and neither are his friends, Sid, the butcher’s boy (baritone, Alfred Mitchell) and Nancy, his girlfriend (mezzo, Megan Baker). One of the delights of this opera is the demotic, everyday language which Britten insisted upon. It is used well and wittily – after his night of debauchery which the May King prize money affords him, Albert thanks the shocked villagers ‘And I’d like to thank you all, for giving me the wherewithal.’ The opera is funny and this production is full of energy, verve and wit. The audience become participants, urged, at specific moments to rise for Lady Billows (as if in church) or to applaud. There are ‘Missing Person’ handbills circulated and beach balls thrown. Throughout, however, the music is spikily superb. Another great success for St Paul’s Opera and a triumphant excursion outside their usual repertoire. The auditorium was almost full last night and the next two night’s are sold out completely.

The opera is funny and this production is full of energy, verve and wit. The audience become participants, urged, at specific moments to rise for Lady Billows (as if in church) or to applaud. There are ‘Missing Person’ handbills circulated and beach balls thrown. Throughout, however, the music is spikily superb. Another great success for St Paul’s Opera and a triumphant excursion outside their usual repertoire. The auditorium was almost full last night and the next two night’s are sold out completely. Britain’s Summer exhibition on Walter Sickert (1860 -1942). A pupil of James Macneill Whistler, friend of Edgar Degas and member of the New English Art Club as well as founding member of the Camden Town Group, Sickert seems to have been the most connected of painters. Forster was twenty years younger (1879 – 1970 ) and, similarly, a member of groups, in his case, the Apostles and then the Bloomsbury Group. Forster went on to pre-eminence, rather more than Sickert did, although the visual artist’s influence is felt, as the exhibition demonstrates, on generations of later painters, especially in England.

Britain’s Summer exhibition on Walter Sickert (1860 -1942). A pupil of James Macneill Whistler, friend of Edgar Degas and member of the New English Art Club as well as founding member of the Camden Town Group, Sickert seems to have been the most connected of painters. Forster was twenty years younger (1879 – 1970 ) and, similarly, a member of groups, in his case, the Apostles and then the Bloomsbury Group. Forster went on to pre-eminence, rather more than Sickert did, although the visual artist’s influence is felt, as the exhibition demonstrates, on generations of later painters, especially in England. The exhibition is also good in showing the young Sickert’s obvious admiration for both his teacher and for Degas. He attempts drawing in Whistler’s style and paints seascapes and urban landscapes and, later in life, attempts the unusual compositional style of Degas. The latter is most evident in the perspectives in pictures, like Trapeze ( so very close to Degas’ Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando

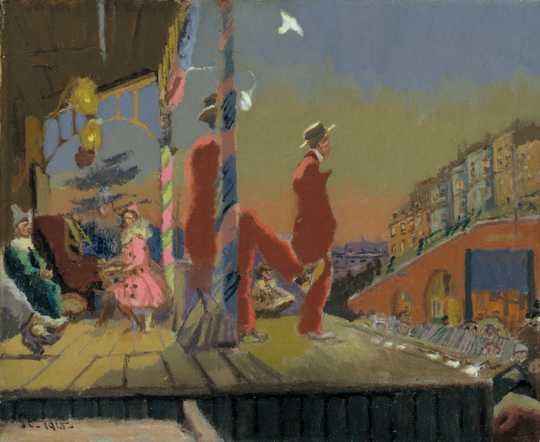

The exhibition is also good in showing the young Sickert’s obvious admiration for both his teacher and for Degas. He attempts drawing in Whistler’s style and paints seascapes and urban landscapes and, later in life, attempts the unusual compositional style of Degas. The latter is most evident in the perspectives in pictures, like Trapeze ( so very close to Degas’ Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando ) and the subject matter – the circus, the music hall and the demi-monde of Paris and London. When considering the paintings, comparisons favour the Frenchman ( and, indeed, the American ) in my view. That said, Sickert produced some wonderful art, very much in his own style. I especially liked his music hall paintings, where the effects of light and the gilded, glistening interiors of the theatres are captured so well. I also enjoyed his urban landscapes.

) and the subject matter – the circus, the music hall and the demi-monde of Paris and London. When considering the paintings, comparisons favour the Frenchman ( and, indeed, the American ) in my view. That said, Sickert produced some wonderful art, very much in his own style. I especially liked his music hall paintings, where the effects of light and the gilded, glistening interiors of the theatres are captured so well. I also enjoyed his urban landscapes. He chose to paint the music hall, rather than the more prestigious venues and concentrated on ordinary urban life, purchasing studios in the 1890s and early 1900s in working class areas the better to draw and paint everyday existence. I also like his way with a single light source, in evidence in the ‘music hall’ pictures but also in little gems like The Acting Manager, a small sketch for a larger painting, found near the beginning of the exhibition.

He chose to paint the music hall, rather than the more prestigious venues and concentrated on ordinary urban life, purchasing studios in the 1890s and early 1900s in working class areas the better to draw and paint everyday existence. I also like his way with a single light source, in evidence in the ‘music hall’ pictures but also in little gems like The Acting Manager, a small sketch for a larger painting, found near the beginning of the exhibition. I liked the solo nudes of ordinary women, often middle-aged and recumbent in non-classical poses, which, clearly, were influential upon later artists, most notably Lucien Freud. Sickert’s heavy impasto style is a forerunner of Bomberg, Auerbach and Gerhardt Richter. I also enjoyed his later paintings with more use of colour, like Brighton Pierrots and his interest in using photographs and photography in his art. In the twenties Sickert mentored and championed the artists in the East London Group; often untutored, working class individuals with little formal education. He encouraged and showed alongside them.

I liked the solo nudes of ordinary women, often middle-aged and recumbent in non-classical poses, which, clearly, were influential upon later artists, most notably Lucien Freud. Sickert’s heavy impasto style is a forerunner of Bomberg, Auerbach and Gerhardt Richter. I also enjoyed his later paintings with more use of colour, like Brighton Pierrots and his interest in using photographs and photography in his art. In the twenties Sickert mentored and championed the artists in the East London Group; often untutored, working class individuals with little formal education. He encouraged and showed alongside them. when researching this article that I discovered the generous patron, the committed supporter of the working class and documentary realism, the teacher ( at Westminster, where David Bomberg was one of his pupils ) and, ultimately, the establishment man – he was President of the Royal Society of British Artists and a Royal Academician, though, typically, he resigned his RA status on a point of principle. I had thought of Sickert as a flamboyant, self-publicising former actor, now I think of him as a guiding force, a helping hand to modern British painting. I don’t know why the exhibition didn’t bring that out more. Perhaps there was a reluctance to focus on the man – in the past much has been made of Sickert’s own interest in Jack the Ripper and Patricia Cornwell’s claim that he was the infamous Jack. Perhaps the curators wanted to concentrate instead on the paintings – entirely understandable.

when researching this article that I discovered the generous patron, the committed supporter of the working class and documentary realism, the teacher ( at Westminster, where David Bomberg was one of his pupils ) and, ultimately, the establishment man – he was President of the Royal Society of British Artists and a Royal Academician, though, typically, he resigned his RA status on a point of principle. I had thought of Sickert as a flamboyant, self-publicising former actor, now I think of him as a guiding force, a helping hand to modern British painting. I don’t know why the exhibition didn’t bring that out more. Perhaps there was a reluctance to focus on the man – in the past much has been made of Sickert’s own interest in Jack the Ripper and Patricia Cornwell’s claim that he was the infamous Jack. Perhaps the curators wanted to concentrate instead on the paintings – entirely understandable. … but rather Albert Herring, by Benjamin Britten. This year’s Summer Opera from St Paul’s Opera Company, Clapham. Last night was the ‘Insight’ evening, designed to introduce the opera to those who may not know it and to stimulate discussion among those who did. I learned a lot.

… but rather Albert Herring, by Benjamin Britten. This year’s Summer Opera from St Paul’s Opera Company, Clapham. Last night was the ‘Insight’ evening, designed to introduce the opera to those who may not know it and to stimulate discussion among those who did. I learned a lot. serious piece The Rape of Lucretia. Albert Herring a chamber opera in three acts, was the result.

serious piece The Rape of Lucretia. Albert Herring a chamber opera in three acts, was the result. The following morning, with Albert missing, the villagers discover his May crown in the well and everyone is thrown into mourning. In its midst Albert turns up, rather the worse for wear and thanks the village committee for funding his night of pleasure. All are, needless to say, outraged, but Albert carries it off, standing up to his mother in the process. The opera was an immediate success, receiving performances in the U.S., Copenhagen, Oslo and Moscow. It has since been performed all over the world.

The following morning, with Albert missing, the villagers discover his May crown in the well and everyone is thrown into mourning. In its midst Albert turns up, rather the worse for wear and thanks the village committee for funding his night of pleasure. All are, needless to say, outraged, but Albert carries it off, standing up to his mother in the process. The opera was an immediate success, receiving performances in the U.S., Copenhagen, Oslo and Moscow. It has since been performed all over the world. Wintle, Panaretos Kyriatzidis (musical director of St Paul’s Opera) and Annemiek van Elst (Director of Albert Herring) facilitated by Jonathan Boardman. The evening closed with questions from the audience (which could have gone on for far longer ). Sadly, dusk had well and truly fallen and the evening drew to a close.

Wintle, Panaretos Kyriatzidis (musical director of St Paul’s Opera) and Annemiek van Elst (Director of Albert Herring) facilitated by Jonathan Boardman. The evening closed with questions from the audience (which could have gone on for far longer ). Sadly, dusk had well and truly fallen and the evening drew to a close. The

The  south London – Clapham in my case, where Cassandra Fortune lives, Dulwich, home of Hannah Weybridge in Anne’s series and Dulwich, Herne Hill and Belsize Park, among others, for Beth Haldane in Alice’s. The tales range across the capital, taking in Westminster, Theatreland, Fleet Street and the yummy mummy nappy valleys of south London as well as rather less salubrious locations, like King’s Cross and Elephant and Castle.

south London – Clapham in my case, where Cassandra Fortune lives, Dulwich, home of Hannah Weybridge in Anne’s series and Dulwich, Herne Hill and Belsize Park, among others, for Beth Haldane in Alice’s. The tales range across the capital, taking in Westminster, Theatreland, Fleet Street and the yummy mummy nappy valleys of south London as well as rather less salubrious locations, like King’s Cross and Elephant and Castle. First stop on the ‘Sister Sleuths’ tour is at

First stop on the ‘Sister Sleuths’ tour is at  is already five books long and Alice’s Beth Haldane (and her on-off boyfriend DI Harry York) has appeared in even more, beginning with Death in Dulwich. I am lagging behind with only two, though that will be increased in the Autumn when Opera, the third Cassandra Fortune is published.

is already five books long and Alice’s Beth Haldane (and her on-off boyfriend DI Harry York) has appeared in even more, beginning with Death in Dulwich. I am lagging behind with only two, though that will be increased in the Autumn when Opera, the third Cassandra Fortune is published. Today’s news media is full of stories about the casual misogyny and sexually predatory culture of the Palace of Westminster ( not just the Commons, though that features more often than the Lords ). This isn’t new. When I was writing Plague (Claret Press, 2020) I was taken to task by one of the readers of an early manuscript. She commented on my depiction of a male dominated, testosterone fuelled, hard drinking place, in which women MPs were treated as decorative, or routinely verbally abused and female civil servants and Parliamentary researchers ‘fair game’, saying it was incorrect to such a degree that no one would believe it in the twenty-first century. I begged to differ.

Today’s news media is full of stories about the casual misogyny and sexually predatory culture of the Palace of Westminster ( not just the Commons, though that features more often than the Lords ). This isn’t new. When I was writing Plague (Claret Press, 2020) I was taken to task by one of the readers of an early manuscript. She commented on my depiction of a male dominated, testosterone fuelled, hard drinking place, in which women MPs were treated as decorative, or routinely verbally abused and female civil servants and Parliamentary researchers ‘fair game’, saying it was incorrect to such a degree that no one would believe it in the twenty-first century. I begged to differ. significant minority who do, as recently confirmed by the current, female, Attorney General, and witness the recent resignation of Neil Parish. The Palace is an unique and strange workplace, with MPs often far from home and under tremendous pressure, from their peers as well as the Whips. There is many an decent, family man (and they do tend to be men, but this isn’t exclusively male) in his constituency who lives a rather different life in Westminster. The ready availability of alcohol (or the stimulant of your choice) doesn’t help either. Catherine Bennett’s article in today’s Observer newspaper lists some examples from the Tory benches (see

significant minority who do, as recently confirmed by the current, female, Attorney General, and witness the recent resignation of Neil Parish. The Palace is an unique and strange workplace, with MPs often far from home and under tremendous pressure, from their peers as well as the Whips. There is many an decent, family man (and they do tend to be men, but this isn’t exclusively male) in his constituency who lives a rather different life in Westminster. The ready availability of alcohol (or the stimulant of your choice) doesn’t help either. Catherine Bennett’s article in today’s Observer newspaper lists some examples from the Tory benches (see  But back to Plague. We have been here before, when the media, or those parts of it more interested in fact than propaganda, reported on the scandals around PPE (and other) contracts handed, without competition, to cronies and the special ‘VIP lane’ of government procurement. There have been successful court cases branding the behaviour of the government unlawful.

But back to Plague. We have been here before, when the media, or those parts of it more interested in fact than propaganda, reported on the scandals around PPE (and other) contracts handed, without competition, to cronies and the special ‘VIP lane’ of government procurement. There have been successful court cases branding the behaviour of the government unlawful. connected with it.

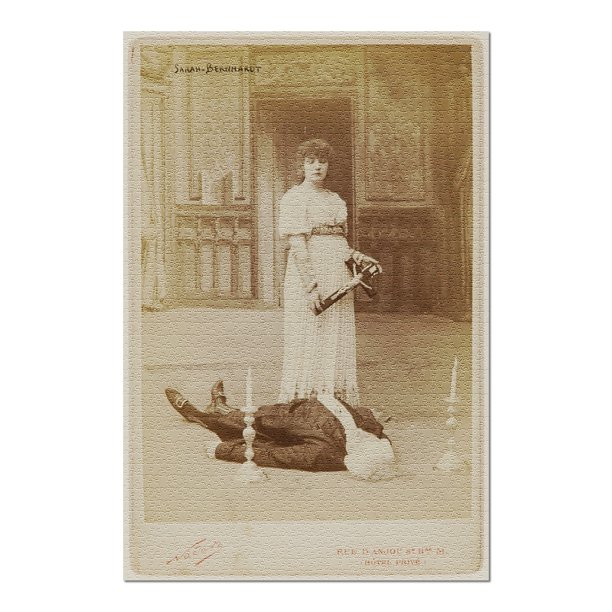

connected with it. Puccini’s opera was based. The first performance of the opera was in 1900 in Rome and the poster was by Adolfo Hohenstein who also designed the stage sets. It is very much in the Art Noveau style of Mucha and features the same scene as the Bernhardt postcard, a scene which was to feature again and again in images of the opera. The pious Tosca sets candles at the head of the Baron, whom she has just killed ( in self-defence, as he has just tried to rape her ) and places a crucifix on his chest.

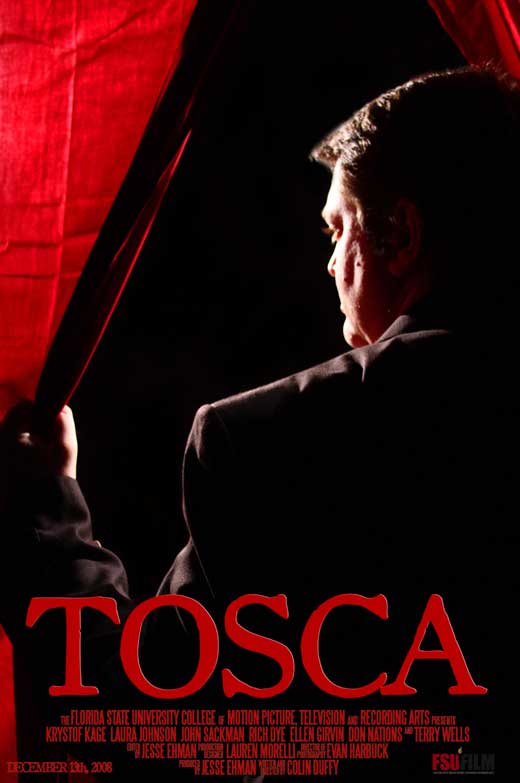

Puccini’s opera was based. The first performance of the opera was in 1900 in Rome and the poster was by Adolfo Hohenstein who also designed the stage sets. It is very much in the Art Noveau style of Mucha and features the same scene as the Bernhardt postcard, a scene which was to feature again and again in images of the opera. The pious Tosca sets candles at the head of the Baron, whom she has just killed ( in self-defence, as he has just tried to rape her ) and places a crucifix on his chest. Many of the more modern images are explicit about the subject matter and the link the opera makes between sex and death (see left). The dagger is a recurring motif, as is blood – red is the most popular colour. The Castel Sant’Angelo appears too. Tosca herself, as in Bernhardt’s time, is often the the central image, although other posters prefer to concentrate on Scarpia, like that for Florida State Opera (right). Only a few depict Cavaradossi, the hero. Ordinarily one might say that this is an example of

Many of the more modern images are explicit about the subject matter and the link the opera makes between sex and death (see left). The dagger is a recurring motif, as is blood – red is the most popular colour. The Castel Sant’Angelo appears too. Tosca herself, as in Bernhardt’s time, is often the the central image, although other posters prefer to concentrate on Scarpia, like that for Florida State Opera (right). Only a few depict Cavaradossi, the hero. Ordinarily one might say that this is an example of  ‘the devil has all the best tunes’, except that in the opera itself, it is the tenor arias, belonging to Cavaradossi, which are most memorable.

‘the devil has all the best tunes’, except that in the opera itself, it is the tenor arias, belonging to Cavaradossi, which are most memorable. A metal box, that’s all it is. Not precious metal either, probably brass, at least that’s how it looks when polished, though bits are silver in colour, so it could possibly be tin or another alloy. Approximately 130 centimetres across, 85 from front edge to back and 30cm/1 inch deep, it would fit in a uniform pocket.

A metal box, that’s all it is. Not precious metal either, probably brass, at least that’s how it looks when polished, though bits are silver in colour, so it could possibly be tin or another alloy. Approximately 130 centimetres across, 85 from front edge to back and 30cm/1 inch deep, it would fit in a uniform pocket. £152, 691 was raised and manufacturing of the boxes began. Although originally meant for ‘every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front’ on Christmas Day 1914, this was widened to include anyone serving, wearing the King’s uniform on Christmas Day. About 400,000 were distributed before or at Christmas, though the tally eventually reached 2.5 million, although many of those weren’t distributed until 1920, after the war was over. ‘Serving’ is appropriate, as I remember, as a child, a ‘christmas box’ was something given to tradespeople, postmen, anyone who had served you well during the year preceding.

£152, 691 was raised and manufacturing of the boxes began. Although originally meant for ‘every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front’ on Christmas Day 1914, this was widened to include anyone serving, wearing the King’s uniform on Christmas Day. About 400,000 were distributed before or at Christmas, though the tally eventually reached 2.5 million, although many of those weren’t distributed until 1920, after the war was over. ‘Serving’ is appropriate, as I remember, as a child, a ‘christmas box’ was something given to tradespeople, postmen, anyone who had served you well during the year preceding. ‘Imperium Britannicus’ and below her a lozenge bearing the inscription ‘Christmas 1914’.

‘Imperium Britannicus’ and below her a lozenge bearing the inscription ‘Christmas 1914’. First at the famed

First at the famed  fabulous side room wall-papered with posters of previous performers. It’s terrifically nostalgic and much time was spent spotting bands we recognised or knew from more youthful days. Zelda Rhiando, herself a published writer and the organiser of the Jam, was there to calm our nerves and point out the beers in the little fridge and the bottles of wine. I swore not to touch a drop before I went on.

fabulous side room wall-papered with posters of previous performers. It’s terrifically nostalgic and much time was spent spotting bands we recognised or knew from more youthful days. Zelda Rhiando, herself a published writer and the organiser of the Jam, was there to calm our nerves and point out the beers in the little fridge and the bottles of wine. I swore not to touch a drop before I went on. Brixton Book Jam was not my only interesting night on the town. Only three days later I attended the first meeting of the London chapter of the

Brixton Book Jam was not my only interesting night on the town. Only three days later I attended the first meeting of the London chapter of the  out of the prison down to the prison hulks moored on the Thames. They would then be removed to the transportation ships bound for Australia. The pub was, Anthony informed us, one of the most haunted in London. But the writers’ imaginations were already hard at work and one of us was already speculating aloud about a crime plot using the tunnels. This is, I guess, the sort of thing that happens when a group of Crime Writers gets together. I’ll be looking forward to the next meeting.

out of the prison down to the prison hulks moored on the Thames. They would then be removed to the transportation ships bound for Australia. The pub was, Anthony informed us, one of the most haunted in London. But the writers’ imaginations were already hard at work and one of us was already speculating aloud about a crime plot using the tunnels. This is, I guess, the sort of thing that happens when a group of Crime Writers gets together. I’ll be looking forward to the next meeting. I hadn’t appreciated the level of sophistication of the dwellers in this land from about 6,000 to 4,000 years ago. The world-view of the earliest, revolving around nature and the seasons, like many hunter-gatherer people, was shared across northern Europe. Of course, until about 6500 BCE and the rising of post Ice Age sea levels, the UK was part of the landmass of that continent. Although subsequently an island archipelago, the peoples who lived here had regular contact with their counterparts on the mainland. This can be seen in their art and craftwork, but also measured by their DNA. One of the most striking examples of this was of the Amesbury Archer. Bones belonging to this man, buried with his bow, were DNA tested. He was originally from the southern Alpine region, though he had lived in southern England for most of his life. Near his grave is that of another, younger man who shares the first’s DNA and is likely to have been his grandson. This man was born and lived most of his life in the Alps, but he was clearly in Amesbury when he met his end. A family visit? Or did the grandson come to live with his grandparents?

I hadn’t appreciated the level of sophistication of the dwellers in this land from about 6,000 to 4,000 years ago. The world-view of the earliest, revolving around nature and the seasons, like many hunter-gatherer people, was shared across northern Europe. Of course, until about 6500 BCE and the rising of post Ice Age sea levels, the UK was part of the landmass of that continent. Although subsequently an island archipelago, the peoples who lived here had regular contact with their counterparts on the mainland. This can be seen in their art and craftwork, but also measured by their DNA. One of the most striking examples of this was of the Amesbury Archer. Bones belonging to this man, buried with his bow, were DNA tested. He was originally from the southern Alpine region, though he had lived in southern England for most of his life. Near his grave is that of another, younger man who shares the first’s DNA and is likely to have been his grandson. This man was born and lived most of his life in the Alps, but he was clearly in Amesbury when he met his end. A family visit? Or did the grandson come to live with his grandparents? beautiful. Perfectly carved and turned stones, with elaborate patterning, these weren’t to be used for everyday, but were ceremonial and included in burials. I was fascinated by one aspect of that early culture, that ‘art’ lay in the act of creation, not, or not only, in the item produced by it. Thus, things did not have the same value as the ability to create them, which seems an eminently sensible value system to me. There is also a wonderful, finely wrought golden collar from this era. Gold was used, not because it had any intrinsic value, but because it was the colour of and reflected the light from, the sun.

beautiful. Perfectly carved and turned stones, with elaborate patterning, these weren’t to be used for everyday, but were ceremonial and included in burials. I was fascinated by one aspect of that early culture, that ‘art’ lay in the act of creation, not, or not only, in the item produced by it. Thus, things did not have the same value as the ability to create them, which seems an eminently sensible value system to me. There is also a wonderful, finely wrought golden collar from this era. Gold was used, not because it had any intrinsic value, but because it was the colour of and reflected the light from, the sun. The exhibition explains, through artefacts, how that culture changed, with the introduction of farming and a concentration on animals and other aspects of nature as a commodity. Art was still relatively fluid, in that stone carvings were made outside and weren’t ‘finished’ objects, but people added to them all the time. This is also true of Stonehenge itself. The landscape in which it was built was already crossed by ceremonial ditches and banks and, after the great sarsen stones were raised, carved on mortice and tenon principles ( see photograph, left) it was added to years later with blue stones brought from Wales, over 220 miles away.

The exhibition explains, through artefacts, how that culture changed, with the introduction of farming and a concentration on animals and other aspects of nature as a commodity. Art was still relatively fluid, in that stone carvings were made outside and weren’t ‘finished’ objects, but people added to them all the time. This is also true of Stonehenge itself. The landscape in which it was built was already crossed by ceremonial ditches and banks and, after the great sarsen stones were raised, carved on mortice and tenon principles ( see photograph, left) it was added to years later with blue stones brought from Wales, over 220 miles away. on Troy. This exhibition places the British pieces in that cross-cultural context, with a collection of armour, roughly contemporaneous to the Illiad and not dissimilar to that worn in ancient Greece (though the helmets look more like Janissaries). There were also exquisite golden drinking bowls and fine copper horsehead artefacts (the horse featured strongly as did the snake, the bird and the sun and moon ). This was a culture close to nature, even when that nature was largely tamed.

on Troy. This exhibition places the British pieces in that cross-cultural context, with a collection of armour, roughly contemporaneous to the Illiad and not dissimilar to that worn in ancient Greece (though the helmets look more like Janissaries). There were also exquisite golden drinking bowls and fine copper horsehead artefacts (the horse featured strongly as did the snake, the bird and the sun and moon ). This was a culture close to nature, even when that nature was largely tamed. the time of the lunar month. This shows a level of sophistication in understanding of the movement of the stars and planets which is reinforced when one sees how many barrows and henges were aligned with sun and, or, moon. The exhibition ranges across many of these, from Denmark, Ireland, the islands of Scotland as well as Wales, Spain, France and elsewhere in England. It also shows how the sea began to play a greater and greater role in the culture of the people living here, as trading took place and the sea itself became a place to worship. There is a recreation of the remarkable Seahenge discovered in the saltmarsh of the Norfolk coast and which, incidentally, features in the crime fiction of Elly Griffiths’ Ruth Galloway books.

the time of the lunar month. This shows a level of sophistication in understanding of the movement of the stars and planets which is reinforced when one sees how many barrows and henges were aligned with sun and, or, moon. The exhibition ranges across many of these, from Denmark, Ireland, the islands of Scotland as well as Wales, Spain, France and elsewhere in England. It also shows how the sea began to play a greater and greater role in the culture of the people living here, as trading took place and the sea itself became a place to worship. There is a recreation of the remarkable Seahenge discovered in the saltmarsh of the Norfolk coast and which, incidentally, features in the crime fiction of Elly Griffiths’ Ruth Galloway books.