Or the sound of the sea. There is nothing quite like that ever repeating, calming background pulse of water falling upon sand. Or indeed the fierce cacophony of wind whipped breakers on rocks or cliffs. Last week I was enjoying the former.

Or the sound of the sea. There is nothing quite like that ever repeating, calming background pulse of water falling upon sand. Or indeed the fierce cacophony of wind whipped breakers on rocks or cliffs. Last week I was enjoying the former.

Twenty minutes drive from Jerez de la Frontera is the sherry town of El Puerto de Santa Maria. It sits at the mouth of the Rio Guadalete, although it would be more accurate to say that it sits upon the river delta, because there is as much sea and marsh as land. Nonetheless the river is in part enclosed here as it runs into the Bay of Cadiz. The town is an old one, it was from here and from Sanlucar de Barrameda that Columbus set sail in the seventeenth century and El Puerto was already old then.

It has its medieval castle and ramparts and many familiar bodega-style buildings, although these are largely symbolic today. It also has a smart central shopping area and a grand Plaza de Toro ( the people of El Puerto are keen on the traditions of old Andalucia and old Spain ). There are plush modern suburbs, like Vista Hermosa, full of large villas built in the traditional style each surrounded by private gardens, often rented out to officers from the American Naval Base at Rota. There are also holiday apartments, in Las Redes and at El Manantial, owned in part by locals, but favoured too by visitors from Madrid and Sevilla.

smart central shopping area and a grand Plaza de Toro ( the people of El Puerto are keen on the traditions of old Andalucia and old Spain ). There are plush modern suburbs, like Vista Hermosa, full of large villas built in the traditional style each surrounded by private gardens, often rented out to officers from the American Naval Base at Rota. There are also holiday apartments, in Las Redes and at El Manantial, owned in part by locals, but favoured too by visitors from Madrid and Sevilla.

El Puerto is much more of a holiday destination than Jerez, with its many beaches which, like all Spanish beaches, have names (see above). There is the town beach, with children’s play areas, soft golden sand and tiled promenade with gardens, Vista Hermosa’s beach, beyond what had used to be the Club 18 -30, which has been raised and is about to be replaced with a five star hotel; and there’s a glossy marina called Puerto Sherry. The Spanish Olympic Yachting Association sails out of here and, on the day when I visited, there were some rather expensive, ocean-going yachts moored behind the lighthouse mole.

El Puerto is much more of a holiday destination than Jerez, with its many beaches which, like all Spanish beaches, have names (see above). There is the town beach, with children’s play areas, soft golden sand and tiled promenade with gardens, Vista Hermosa’s beach, beyond what had used to be the Club 18 -30, which has been raised and is about to be replaced with a five star hotel; and there’s a glossy marina called Puerto Sherry. The Spanish Olympic Yachting Association sails out of here and, on the day when I visited, there were some rather expensive, ocean-going yachts moored behind the lighthouse mole.

There were some rather expensive bars too. Sotavento is superbly positioned just where the marina meets the Bay (see photos, courtesy of Deborah Powell) with a view across to Cadiz and one pays a premium for the location. When we visited there was the bonus of a tall ship. The people frequenting the bars along here are, largely, wealthy holiday makers and yacht owners, Spanish and foreign. The locals work in them. They were, however, extremely welcoming of Thai and Goa, Deborah’s two labradors. We sat and watched the sun set and the lights of Cadiz begin to glow.

the Bay (see photos, courtesy of Deborah Powell) with a view across to Cadiz and one pays a premium for the location. When we visited there was the bonus of a tall ship. The people frequenting the bars along here are, largely, wealthy holiday makers and yacht owners, Spanish and foreign. The locals work in them. They were, however, extremely welcoming of Thai and Goa, Deborah’s two labradors. We sat and watched the sun set and the lights of Cadiz begin to glow.

Twenty four hours later I did the same at El Manantial, half a mile further north, a beach which lies up against the perimeter of the aforementioned naval base. On that occasion I was with my friend from Jerez and her three dogs. She has a beach-house there, where there were few foreigners, but plenty of Spanish folk enjoying the last of summer, once the ‘tourists’ have  gone back to the city. The beach bars are few and far between, though the clam sellers (and sellers of sweets and snacks) push their gaily coloured carts along on the hard sand, crying their wares. Much less smart. And soon they too would pack up and leave, the season having finished. The beach would become much quieter, the bailiwick of locals only.

gone back to the city. The beach bars are few and far between, though the clam sellers (and sellers of sweets and snacks) push their gaily coloured carts along on the hard sand, crying their wares. Much less smart. And soon they too would pack up and leave, the season having finished. The beach would become much quieter, the bailiwick of locals only.

Again I watched the sun set and the lights of Cadiz twinkling on the horizon, before heading back to a Jerez still celebrating the Vendimia (with a ferris wheel in Plaza Arenal!). Two beaches, both in El Puerto and so close to each other, but so different. In both there was the sound of the sea.

still finding interesting places new to me, sometimes close to home. Ten days ago I found myself in Stockwell.

still finding interesting places new to me, sometimes close to home. Ten days ago I found myself in Stockwell. Leisure Magazine. It was somewhat daunting, to be interviewing the man who had interviewed so many famous, and infamous, people and whose voice had formed part of the backdrop to my mornings for so many years. Stourton was a main presenter on Radio 4’s Today Programme for a decade – as well as The World at One and The World This Weekend, both of which he still does on occasion.

Leisure Magazine. It was somewhat daunting, to be interviewing the man who had interviewed so many famous, and infamous, people and whose voice had formed part of the backdrop to my mornings for so many years. Stourton was a main presenter on Radio 4’s Today Programme for a decade – as well as The World at One and The World This Weekend, both of which he still does on occasion. not to be late, I was ridiculously early. So I wandered towards the address I had been given and discovered, for the first time, Stockwell Park or the Stockwell Conservation Area. It received that designation in 1973 and covers the old Stockwell Green (the 15th century manor house which formerly stood there has links with Thomas Cromwell) and the later 19th century developments of Stockwell Crescent and the roads running from it. Built primarily in the 1830s the surviving buildings are elegant early Victorian villas with gardens. They were built to different designs, which distinguishes them from the smaller, ‘pattern built’ south London Victoriana elsewhere (like some of my beloved Clapham).

not to be late, I was ridiculously early. So I wandered towards the address I had been given and discovered, for the first time, Stockwell Park or the Stockwell Conservation Area. It received that designation in 1973 and covers the old Stockwell Green (the 15th century manor house which formerly stood there has links with Thomas Cromwell) and the later 19th century developments of Stockwell Crescent and the roads running from it. Built primarily in the 1830s the surviving buildings are elegant early Victorian villas with gardens. They were built to different designs, which distinguishes them from the smaller, ‘pattern built’ south London Victoriana elsewhere (like some of my beloved Clapham). found St Michael’s Church of England church (consecrated 1841) and a blue plaque marking the home of Lillian Bayliss, Director of the Old Vic and Sadlers Wells theatres and founder of the forerunners of the English National Opera, the National Theatre and the Royal Ballet. The whole enclave was a delight and so very near to the busy Stockwell Road which runs directly into the City. I never knew it existed.

found St Michael’s Church of England church (consecrated 1841) and a blue plaque marking the home of Lillian Bayliss, Director of the Old Vic and Sadlers Wells theatres and founder of the forerunners of the English National Opera, the National Theatre and the Royal Ballet. The whole enclave was a delight and so very near to the busy Stockwell Road which runs directly into the City. I never knew it existed.

On a grey and somewhat chilly Bank Holiday Sunday English National Opera, with the full ENO orchestra and chorus and soloists David Junghoon Kim, Natalya Romaniw and Roland Wood were at Crystal Palace Park. So were we.

On a grey and somewhat chilly Bank Holiday Sunday English National Opera, with the full ENO orchestra and chorus and soloists David Junghoon Kim, Natalya Romaniw and Roland Wood were at Crystal Palace Park. So were we. couple of burger joints, a pizza place, churros and sushi – with long queues, which meant people walking back to their places bearing food after the performance had commenced. There were bars aplenty, unfortunately they sold only hugely overpriced cans – of beer, of wine and of gin & tonic. No draught beer, no bottles of wine. And no bringing your own drinks with you. We knew this, so didn’t try, but others clearly did not and had their goodies confiscated at the entrance. Given the lack of choice and the prices charged this left a sour taste in a lot of mouths.

couple of burger joints, a pizza place, churros and sushi – with long queues, which meant people walking back to their places bearing food after the performance had commenced. There were bars aplenty, unfortunately they sold only hugely overpriced cans – of beer, of wine and of gin & tonic. No draught beer, no bottles of wine. And no bringing your own drinks with you. We knew this, so didn’t try, but others clearly did not and had their goodies confiscated at the entrance. Given the lack of choice and the prices charged this left a sour taste in a lot of mouths. the back of Zone A, only a few yards from where we sat. They weren’t pleased and understandably so.

the back of Zone A, only a few yards from where we sat. They weren’t pleased and understandably so. and powerful Cavaradossi who reached those high notes with ease. Romaniw was empassioned and exquisite – even in a park and with an audience this big, you could have heard a pin drop during ‘Vissi d’arte‘. At the end, everyone was on their feet and clapping and cheering ( and booing Scarpia, who was an excellent Roland Wood ). Though there were also folk beginning to clear away their things – it was cold by this time. The group to the immediate right of us had brought duvets, they were snug.

and powerful Cavaradossi who reached those high notes with ease. Romaniw was empassioned and exquisite – even in a park and with an audience this big, you could have heard a pin drop during ‘Vissi d’arte‘. At the end, everyone was on their feet and clapping and cheering ( and booing Scarpia, who was an excellent Roland Wood ). Though there were also folk beginning to clear away their things – it was cold by this time. The group to the immediate right of us had brought duvets, they were snug. Last weekend I submitted the manuscript of Opera to Claret Press. Then I went and made some jam.

Last weekend I submitted the manuscript of Opera to Claret Press. Then I went and made some jam. what extremely hard work. It’s a business, an industry and many of those toiling within it do so for very little reward and recognition. As with any industry the larger entities, the Hachettes and Harper Collins, will have greater reach and a higher profile ( placing their books on supermarket shelves for example ) and the big corporate vendors, the Amazons and Waterstones will also skew the market towards those books which get the publicity and the coverage. As my friend and fellow Claret author, Steve Sheppard, says in the note in his latest novel Bored to Death in the Baltics, he ‘ought to have tried to become a celebrity first, as this would have made selling it (the book) so much easier’.

what extremely hard work. It’s a business, an industry and many of those toiling within it do so for very little reward and recognition. As with any industry the larger entities, the Hachettes and Harper Collins, will have greater reach and a higher profile ( placing their books on supermarket shelves for example ) and the big corporate vendors, the Amazons and Waterstones will also skew the market towards those books which get the publicity and the coverage. As my friend and fellow Claret author, Steve Sheppard, says in the note in his latest novel Bored to Death in the Baltics, he ‘ought to have tried to become a celebrity first, as this would have made selling it (the book) so much easier’.  I have come to genuinely enjoy this process, though it sometimes isn’t a comfortable one. People get passionate about a work, there are disagreements and I, like any writer, am possessive about my stories. I expect to know them better and know what’s best for them, despite evidence to the contrary. But for now I have a moment’s respite, maybe a fortnight, maybe longer. I can sit back, read other books, do the garden, catch up on all those jobs… and make more jam.

I have come to genuinely enjoy this process, though it sometimes isn’t a comfortable one. People get passionate about a work, there are disagreements and I, like any writer, am possessive about my stories. I expect to know them better and know what’s best for them, despite evidence to the contrary. But for now I have a moment’s respite, maybe a fortnight, maybe longer. I can sit back, read other books, do the garden, catch up on all those jobs… and make more jam. Yesterday to the British Museum during the last week of the exhibition Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint which ends on Sunday. It’s an interesting exhibition which follows Becket’s upbringing, fairly meteoric career ( from Cheapside immigrant merchant’s son to the Archbishopric and Lord Chancellorship of England ) to his eventual death and subsequent canonisation. I reread Murder in the Cathedral in preparation and the exhibition ends with lines from that verse play.

Yesterday to the British Museum during the last week of the exhibition Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint which ends on Sunday. It’s an interesting exhibition which follows Becket’s upbringing, fairly meteoric career ( from Cheapside immigrant merchant’s son to the Archbishopric and Lord Chancellorship of England ) to his eventual death and subsequent canonisation. I reread Murder in the Cathedral in preparation and the exhibition ends with lines from that verse play. seemed to me and my companion, also sought martyrdom as the ultimate step, a translation into immortality. Everyone knows the story, or has seen the film and recognises the famous quote ‘Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?’, although this is, without explanation, changed to ‘Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?’ in this exhibition.

seemed to me and my companion, also sought martyrdom as the ultimate step, a translation into immortality. Everyone knows the story, or has seen the film and recognises the famous quote ‘Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?’, although this is, without explanation, changed to ‘Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?’ in this exhibition.  British Museum curators shouldn’t, in my view, be saying it is because, aside from anything else, it will then become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Three young people, unknown to me, but who went round the exhibition at approximately the same time as I did, clearly took away this ‘story’ without its context. Henry might not be a popular, or even a colourful, character, by all accounts he was a choleric and sometimes harsh individual, but he also inherited a cash-strapped and exhausted land, following the war between Stephen and Matilda ( Henry’s mother ). Just because he isn’t particularly likeable doesn’t mean his role in history should be limited to his role in a martyrdom. In my humble opinion, it’s bad history ( even if it is good story telling. ) The richness and complexity of life, even life in the past, is reduced in this way. Rant over.

British Museum curators shouldn’t, in my view, be saying it is because, aside from anything else, it will then become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Three young people, unknown to me, but who went round the exhibition at approximately the same time as I did, clearly took away this ‘story’ without its context. Henry might not be a popular, or even a colourful, character, by all accounts he was a choleric and sometimes harsh individual, but he also inherited a cash-strapped and exhausted land, following the war between Stephen and Matilda ( Henry’s mother ). Just because he isn’t particularly likeable doesn’t mean his role in history should be limited to his role in a martyrdom. In my humble opinion, it’s bad history ( even if it is good story telling. ) The richness and complexity of life, even life in the past, is reduced in this way. Rant over. as the murder itself. I was intrigued to find out about the broken sword and the depiction which showed this, as well as a chunk of skull falling to the flagstones of the cathedral floor. It’s interesting that these small, if gory, details survived and thrived in later representations of the scene. I was surprised by the far-flung examples of the Becket cult – stone carving from Sweden, a reliquary from Norway, reference in a parchment from Italy. Maybe I shouldn’t have been, the Church stretched across Europe and its saints were promoted widely.

as the murder itself. I was intrigued to find out about the broken sword and the depiction which showed this, as well as a chunk of skull falling to the flagstones of the cathedral floor. It’s interesting that these small, if gory, details survived and thrived in later representations of the scene. I was surprised by the far-flung examples of the Becket cult – stone carving from Sweden, a reliquary from Norway, reference in a parchment from Italy. Maybe I shouldn’t have been, the Church stretched across Europe and its saints were promoted widely. The airport wasn’t crowded (no queues at Pret for the in-flight sandwich) though that may have had something to do with the hour – it was 5 a.m.. That’s the downside of my Ryanair flight to Jerez, the only flight available. There’s no public transport at that time in the morning either, but Pepe, my cabbie from Congo, was fun to talk to on the way. The cab from south London wasn’t cheap, but then the flight tickets were, so… My flight, on time and comfortable, was far from full.

The airport wasn’t crowded (no queues at Pret for the in-flight sandwich) though that may have had something to do with the hour – it was 5 a.m.. That’s the downside of my Ryanair flight to Jerez, the only flight available. There’s no public transport at that time in the morning either, but Pepe, my cabbie from Congo, was fun to talk to on the way. The cab from south London wasn’t cheap, but then the flight tickets were, so… My flight, on time and comfortable, was far from full.

evidence that a PCR test has been booked for one’s return. I had organised these last two before I’d left the UK and the arrangements worked well, especially the Antigen Test with Zoom, which I did when there in collaboration with a nurse who was online, somewhere else in the world. This method was considerably cheaper than any other that I’d found and entirely acceptable to the UK authorities.

evidence that a PCR test has been booked for one’s return. I had organised these last two before I’d left the UK and the arrangements worked well, especially the Antigen Test with Zoom, which I did when there in collaboration with a nurse who was online, somewhere else in the world. This method was considerably cheaper than any other that I’d found and entirely acceptable to the UK authorities.  code which successful submission generated on my phone. Rather more than a fellow traveller on the return journey had managed. He was in transit only through Stansted and hadn’t completed the Form but the Ryanair people insisted. They turned another woman away, who had failed to take a test. Her excuse was that she had planned to take one at the airport – it didn’t work, Jerez airport is very small, without any testing facilities. Other airports may offer this service, but she really should have checked.

code which successful submission generated on my phone. Rather more than a fellow traveller on the return journey had managed. He was in transit only through Stansted and hadn’t completed the Form but the Ryanair people insisted. They turned another woman away, who had failed to take a test. Her excuse was that she had planned to take one at the airport – it didn’t work, Jerez airport is very small, without any testing facilities. Other airports may offer this service, but she really should have checked. Opera noun, Italian, feminine 1 work: 2 task, job: 3 artistic creation: 4 action, deed, handiwork: opere buone goods deeds: opera lettararia literary work: opera musicale opera: opera lirica opera.

Opera noun, Italian, feminine 1 work: 2 task, job: 3 artistic creation: 4 action, deed, handiwork: opere buone goods deeds: opera lettararia literary work: opera musicale opera: opera lirica opera. the Prime Minister, but, in Oracle she learned that this wasn’t enough and she would have to address certain matters arising from her past if she wanted to escape them. Thus she sets out, at the beginning of the third book, to find out the truth of what happened at Government Communications Head Quarters (GCHQ), her former posting, when she was forced to leave it. Until now she had believed her dismissal was because of her own failings, but begins to see that there may have been other forces at work.

the Prime Minister, but, in Oracle she learned that this wasn’t enough and she would have to address certain matters arising from her past if she wanted to escape them. Thus she sets out, at the beginning of the third book, to find out the truth of what happened at Government Communications Head Quarters (GCHQ), her former posting, when she was forced to leave it. Until now she had believed her dismissal was because of her own failings, but begins to see that there may have been other forces at work. the Pythia did (though without the psychotropic gases). Cassie sought guidance from the Pythia and in Opera she seeks it from Angela. Both provide answers couched in riddles.

the Pythia did (though without the psychotropic gases). Cassie sought guidance from the Pythia and in Opera she seeks it from Angela. Both provide answers couched in riddles. …is what I’m experiencing as I edit Opera.

…is what I’m experiencing as I edit Opera. major thoroughfares and in shops, pubs and public buildings. The carol concerts at St Martins and St Johns, the pantomimes in theatreland, the ‘Christmas show’ at the National Theatre (I have seen many over the years) and at least one, often two, productions of The Nutcracker ballet. All this contributes to the backdrop against which Opera takes place.

major thoroughfares and in shops, pubs and public buildings. The carol concerts at St Martins and St Johns, the pantomimes in theatreland, the ‘Christmas show’ at the National Theatre (I have seen many over the years) and at least one, often two, productions of The Nutcracker ballet. All this contributes to the backdrop against which Opera takes place. Each book is organised on a day by day basis. Plague runs over ten days from Monday 9th September to Wednesday 18th with a final chapter on Friday20th. Oracle begins on a Monday in November with six days in Delphi and two more, a week later, in Athens. Readers say that they like this aspect of the novels, making events seem more real and immediate as well, I am told, as pacey. Opera is no exception and a lot happens in ten days, as, I hope, readers have come to expect.

Each book is organised on a day by day basis. Plague runs over ten days from Monday 9th September to Wednesday 18th with a final chapter on Friday20th. Oracle begins on a Monday in November with six days in Delphi and two more, a week later, in Athens. Readers say that they like this aspect of the novels, making events seem more real and immediate as well, I am told, as pacey. Opera is no exception and a lot happens in ten days, as, I hope, readers have come to expect. gives our main suspects an alibi – but wait, who arrived when and who was late? The Palace of Westminster becomes relatively deserted as Members head off to their homes and constituencies and it turns into the haunt of the permanent staff and the tourists, who, while the Houses aren’t sitting, get let into the Chambers. N.B. For anyone who hasn’t visited the Palace of Westminster, the Christmas recess is a good time to go, there are generally fewer tourists than in the summer months.

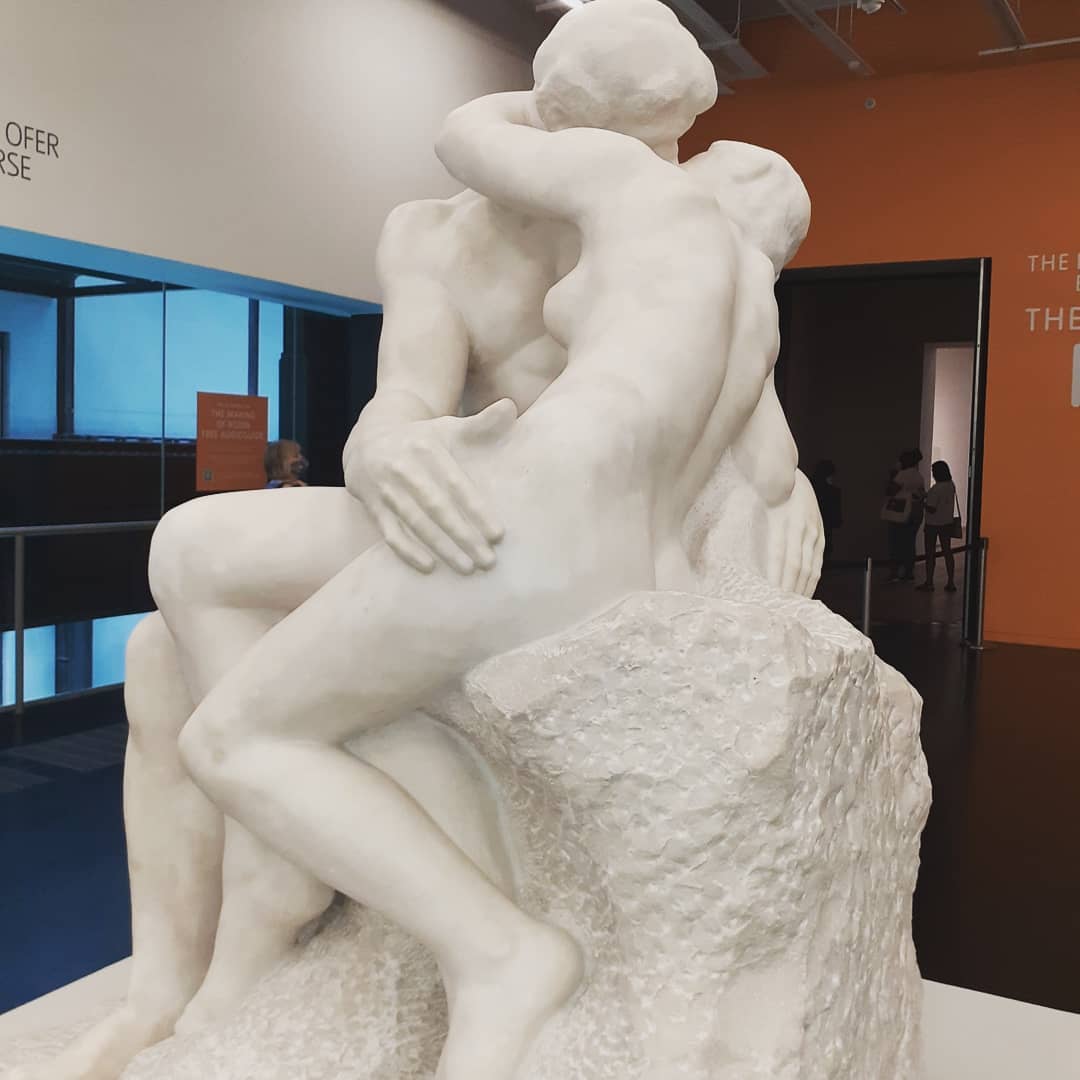

gives our main suspects an alibi – but wait, who arrived when and who was late? The Palace of Westminster becomes relatively deserted as Members head off to their homes and constituencies and it turns into the haunt of the permanent staff and the tourists, who, while the Houses aren’t sitting, get let into the Chambers. N.B. For anyone who hasn’t visited the Palace of Westminster, the Christmas recess is a good time to go, there are generally fewer tourists than in the summer months. I know nothing about sculpting, though I like looking at sculptures. So I found Tate Britain’s exhibition, The Making of Rodin, fascinating, focusing as it does on HOW Rodin went about creating his works. Outside the exhibition is a version of The Kiss, but the show itself begins with a bronze, the only bronze sculpture in the exhibition, the rest are in plaster. This is The Age of Bronze, the figure of a young Belgian soldier named Auguste Ney and it replicated real life so perfectly that Rodin was accused of making the cast direct from Ney’s body rather than modelling it. Rodin refuted the allegations of ‘cheating’ with a passion, having photographs taken of Ney to demonstrate the differences between the subject and the sculpture. Thereafter he was to move away from the conventions of classical sculpture, with its ideal of human beauty.

I know nothing about sculpting, though I like looking at sculptures. So I found Tate Britain’s exhibition, The Making of Rodin, fascinating, focusing as it does on HOW Rodin went about creating his works. Outside the exhibition is a version of The Kiss, but the show itself begins with a bronze, the only bronze sculpture in the exhibition, the rest are in plaster. This is The Age of Bronze, the figure of a young Belgian soldier named Auguste Ney and it replicated real life so perfectly that Rodin was accused of making the cast direct from Ney’s body rather than modelling it. Rodin refuted the allegations of ‘cheating’ with a passion, having photographs taken of Ney to demonstrate the differences between the subject and the sculpture. Thereafter he was to move away from the conventions of classical sculpture, with its ideal of human beauty. platre‘, which softened the sculptures, smoothing their angles and filling their craters. But a perfect finish was not what he was after and he left seams visible between joints as well as gouge and nail marks. Multiple casts of a single piece, or part of a piece were made and used in a variety of ways ( see the Giblets or abattis laid out in one vitrine, arms, legs, torsos originally to be part of The Gates of Hell, but used for many other works ). He reworked his casts, remodelling parts of them, with elements being used in any number of larger works, dismantling and reassembling existing sculptures in endless combinations. So The Head of a Slavic Woman appeared in multiple works, repositioned and rotated. The Son of Ugolino moved from prone point of death to an aerial figure.

platre‘, which softened the sculptures, smoothing their angles and filling their craters. But a perfect finish was not what he was after and he left seams visible between joints as well as gouge and nail marks. Multiple casts of a single piece, or part of a piece were made and used in a variety of ways ( see the Giblets or abattis laid out in one vitrine, arms, legs, torsos originally to be part of The Gates of Hell, but used for many other works ). He reworked his casts, remodelling parts of them, with elements being used in any number of larger works, dismantling and reassembling existing sculptures in endless combinations. So The Head of a Slavic Woman appeared in multiple works, repositioned and rotated. The Son of Ugolino moved from prone point of death to an aerial figure.  Rodin took repetition to another level when he included multiple casts of the same figure to form a sculptural group. So The Three Shades consists of a single figure, originally to represent Adam, presented in a group together (see left). He also changed the scale of pieces and the exhibition has some truly large versions of elements of other sculptures, Rodin was said to be particularly fond of the undulating surfaces created by enlargement. We see the head of one of the Burghers of Calais, but twice the size, a massive version of The Thinker and a super large plaster version of Balzac. The versions of this last sculpture are particularly illuminating, showing a nude figure in various sizes and a head in various forms, plus the dressing gown (so accurately represented it seemed that the fabric would fold in your hand), which were used to inform the final work.

Rodin took repetition to another level when he included multiple casts of the same figure to form a sculptural group. So The Three Shades consists of a single figure, originally to represent Adam, presented in a group together (see left). He also changed the scale of pieces and the exhibition has some truly large versions of elements of other sculptures, Rodin was said to be particularly fond of the undulating surfaces created by enlargement. We see the head of one of the Burghers of Calais, but twice the size, a massive version of The Thinker and a super large plaster version of Balzac. The versions of this last sculpture are particularly illuminating, showing a nude figure in various sizes and a head in various forms, plus the dressing gown (so accurately represented it seemed that the fabric would fold in your hand), which were used to inform the final work. that Rodin used drawing to study movement and the internal dynamics of the body, asking his sitters to move around the studio. The works on show are all of impersonal female nudes in graphite and watercolour and they are full of movement. I liked them a lot. As with his clay sculptures, Rodin would use the sketches again and again. The drawings on display are annotated with his notes, rotating the pages around to show the figures differently depending on aspect. The other element I admired was his use of antique artefacts – a very modern concept – though Rodin used the real thing, not copies, thus effectively negating the work of the original potter, or ceramicist (not so admirable).

that Rodin used drawing to study movement and the internal dynamics of the body, asking his sitters to move around the studio. The works on show are all of impersonal female nudes in graphite and watercolour and they are full of movement. I liked them a lot. As with his clay sculptures, Rodin would use the sketches again and again. The drawings on display are annotated with his notes, rotating the pages around to show the figures differently depending on aspect. The other element I admired was his use of antique artefacts – a very modern concept – though Rodin used the real thing, not copies, thus effectively negating the work of the original potter, or ceramicist (not so admirable). One room contains a life-size ( i.e. bigger than actual life ) plaster model of his famous Burghers of Calais, such a fabulous and powerful sculptural group, the bronze version of which stands outside the Houses of Parliament. This made me want to go and see that sculpture again, but the plain white of the plaster version somehow renders the self-sacrificing burghers even more exposed than their bronze equivalents. Other rooms are dedicated to works depicting the Japanese actor and dancer Ohta Hisa – Rodin made over fifty busts and masks of her face – and Helene von Nostitz, his aristocratic German friend.

One room contains a life-size ( i.e. bigger than actual life ) plaster model of his famous Burghers of Calais, such a fabulous and powerful sculptural group, the bronze version of which stands outside the Houses of Parliament. This made me want to go and see that sculpture again, but the plain white of the plaster version somehow renders the self-sacrificing burghers even more exposed than their bronze equivalents. Other rooms are dedicated to works depicting the Japanese actor and dancer Ohta Hisa – Rodin made over fifty busts and masks of her face – and Helene von Nostitz, his aristocratic German friend.  As readers of Plague will know London hosts many a Roman remnant, from the baths beneath the West End to the Temple of Mithras underneath the Bank of England, but on Friday last I went to see those currently on show at the British Museum in the exhibition Nero: the man behind the myth.

As readers of Plague will know London hosts many a Roman remnant, from the baths beneath the West End to the Temple of Mithras underneath the Bank of England, but on Friday last I went to see those currently on show at the British Museum in the exhibition Nero: the man behind the myth.  for nine days – but he wasn’t alone in doing so. He did commit murders, at least indirectly – first century Roman palace power plays were brutal and murderous. There is evidence, however, that he cared about the people of the city – he instigated relief efforts after the Great Fire, offering shelter in his own palaces and organising food supplies and he started a very large rebuilding programme soon after. It’s almost certain that he was innocent of initiating the fire. The plebs certainly thought better of him than their Senatorial ‘betters’, Nero’s is the imperial name most often found in positive ancient graffiti. He improved the road to Ostia, Rome’s harbour where the grain shipments arrived, so as to protect the city’s food supply and insisted that the rebuilt Rome had better standards of housing. So, not all bad then.

for nine days – but he wasn’t alone in doing so. He did commit murders, at least indirectly – first century Roman palace power plays were brutal and murderous. There is evidence, however, that he cared about the people of the city – he instigated relief efforts after the Great Fire, offering shelter in his own palaces and organising food supplies and he started a very large rebuilding programme soon after. It’s almost certain that he was innocent of initiating the fire. The plebs certainly thought better of him than their Senatorial ‘betters’, Nero’s is the imperial name most often found in positive ancient graffiti. He improved the road to Ostia, Rome’s harbour where the grain shipments arrived, so as to protect the city’s food supply and insisted that the rebuilt Rome had better standards of housing. So, not all bad then.  look at the historical sources. That Nero was ruthless and brutal – well, which Emperor could have ruled Rome for fourteen tumultuous years if he hadn’t been? That he ‘fiddled while Rome burned’ or at least played a lyre, comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio, historians writing during the age of later emperors and whose interests were served by making their masters look good in comparison. Tacitus, who was actually alive at the time of the fire, places Nero outside Rome when the fire happened. Given the title of the exhibition I was hoping there would be more exploration of how and why myths like those surrounding Nero were formed and how common ‘stories’ sometimes reveal a deeper truth, but that wasn’t where this was going.

look at the historical sources. That Nero was ruthless and brutal – well, which Emperor could have ruled Rome for fourteen tumultuous years if he hadn’t been? That he ‘fiddled while Rome burned’ or at least played a lyre, comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio, historians writing during the age of later emperors and whose interests were served by making their masters look good in comparison. Tacitus, who was actually alive at the time of the fire, places Nero outside Rome when the fire happened. Given the title of the exhibition I was hoping there would be more exploration of how and why myths like those surrounding Nero were formed and how common ‘stories’ sometimes reveal a deeper truth, but that wasn’t where this was going. One story I’ve come across, though I’m not sure how true it is, is about his meeting with the Pythia of Delphi. Nero toured Greece in CE 66/67 when he granted the Greeks their ‘freedom’ ( largely from the steep taxes Rome imposed upon client peoples ) and took part in the Isthmian Games. Like anyone who was anyone in the ancient world, he went to Delphi. The Pythia forbade his entry to the Temple of Apollo, calling him a matricide and telling him that the number 73 would mark the hour of his downfall. He had her burned alive ( or so Dio Cassius says ) but took her words to mean that he would live until a ripe old age. In fact he was deposed only a year or so later, by the general, later Emperor, Galba, who happened to be 73 years old at the time ( or so the story goes ). What to take from this, other than not to cross a pythia, I’m not at all sure, but then, all stories about the Pythia tend to show how she was right in the end. Not much consolation when you’re killed horribly. It makes the murder in Oracle look tame in comparison.

One story I’ve come across, though I’m not sure how true it is, is about his meeting with the Pythia of Delphi. Nero toured Greece in CE 66/67 when he granted the Greeks their ‘freedom’ ( largely from the steep taxes Rome imposed upon client peoples ) and took part in the Isthmian Games. Like anyone who was anyone in the ancient world, he went to Delphi. The Pythia forbade his entry to the Temple of Apollo, calling him a matricide and telling him that the number 73 would mark the hour of his downfall. He had her burned alive ( or so Dio Cassius says ) but took her words to mean that he would live until a ripe old age. In fact he was deposed only a year or so later, by the general, later Emperor, Galba, who happened to be 73 years old at the time ( or so the story goes ). What to take from this, other than not to cross a pythia, I’m not at all sure, but then, all stories about the Pythia tend to show how she was right in the end. Not much consolation when you’re killed horribly. It makes the murder in Oracle look tame in comparison. fascinating bunch, they still exert a celebrity-style, dark and seductive glamour even today, that it’s engaging. Some of the exhibits are exquisite – the jewellery, for example, or gruesome – the heavy slave chains, or the gladiator armour and the visitor forms a more rounded picture of the emperor, much more nuanced than the popular myth would have us believe. A good exhibition, worth visiting, that will make you reassess your understanding of Nero, but prepare to concentrate, there are a lot of coins.

fascinating bunch, they still exert a celebrity-style, dark and seductive glamour even today, that it’s engaging. Some of the exhibits are exquisite – the jewellery, for example, or gruesome – the heavy slave chains, or the gladiator armour and the visitor forms a more rounded picture of the emperor, much more nuanced than the popular myth would have us believe. A good exhibition, worth visiting, that will make you reassess your understanding of Nero, but prepare to concentrate, there are a lot of coins.