Given the recent 80th anniversary of VE Day, I have chosen three books with a World War Two setting. They are all standalone mysteries but are also part of a series. Settle into an armchair and immerse yourselves in a world made dangerous by bombs and Nazis, as well as criminals.

My first book is Banquet of Beggars by Chris Lloyd (Orion, £9.99). This is the third in his Occupation series, the first of which, The Unwanted Dead, won the Historical Writers Association Gold Crown Award for the best historical fiction in 2021. The next two books are just as good. Lloyd’s hero is Inspector Eddie Giral, Parisian cop. Once a First World War veteran and family man, once a nightclub bouncer and cokehead, now a laconic and cynical flic who is dangerously close to self-destruction. In 1940, Eddie, all of Paris, is under the rule of the occupying German forces.

My first book is Banquet of Beggars by Chris Lloyd (Orion, £9.99). This is the third in his Occupation series, the first of which, The Unwanted Dead, won the Historical Writers Association Gold Crown Award for the best historical fiction in 2021. The next two books are just as good. Lloyd’s hero is Inspector Eddie Giral, Parisian cop. Once a First World War veteran and family man, once a nightclub bouncer and cokehead, now a laconic and cynical flic who is dangerously close to self-destruction. In 1940, Eddie, all of Paris, is under the rule of the occupying German forces.

Lloyd conjures a bitterly cold and hungry city, where the streets are empty of all but bicycles and German transport. Parisians grow truculent and rebellious as their overlords begin to show the iron fist. While Paris starves, the Germans, and some French, enjoy the very best that the city can offer. The general population resorts to the thriving black market and it is that black market which Eddie investigates after a murder, determined to find a measure of justice, despite the criminal complicity of the occupiers – a complex and dangerous mission. The Parisian underworld is evocatively drawn, as are the minor transgressions forced upon ordinary citizens so as to survive. This is a city where there are few moral certainties.

Eddie is a multi-layered protagonist, trying to do the right thing in impossible circumstances. He is despised by both the Germans and the Parisians, who see him as a coward and collaborator. His sparring with the German who is the liaison officer with the French police, the urbane and menacing Major Hochstetter, is one of the most intriguing relationships in the book. Lloyd entangles the reader in the politics of the occupiers, their ambitions, loyalties and internecine quarrels, as the Gestapo and SS attempt to take over command of the city, but it is Eddie, imperfect but humane, who captures the reader.

My next two recommendations have British settings.

Death of an Officer by Mark Ellis (Headline, £10.99) is set in post-Blitz London in Spring 1943. His protagonist is Detective Chief Inspector Frank Merlin, incorruptible Scotland Yard policeman. Merlin doesn’t quite fit with the establishment, he’s the half Spanish son of an East End chandler and his cockney wife, yet he commands respect amongst the gangland underworld and his fellow coppers (many of whom are corrupt). There are two murders for him and his small team, depleted because of wartime conscription, to solve. First, that of a respected consultant surgeon of Indian extraction, killed in his Kensington flat and, later, the discovery of an unidentified corpse on a bombsite in Limehouse, an apparently well-to-do, young man dressed for a night out ‘up West’.

Inspector Frank Merlin, incorruptible Scotland Yard policeman. Merlin doesn’t quite fit with the establishment, he’s the half Spanish son of an East End chandler and his cockney wife, yet he commands respect amongst the gangland underworld and his fellow coppers (many of whom are corrupt). There are two murders for him and his small team, depleted because of wartime conscription, to solve. First, that of a respected consultant surgeon of Indian extraction, killed in his Kensington flat and, later, the discovery of an unidentified corpse on a bombsite in Limehouse, an apparently well-to-do, young man dressed for a night out ‘up West’.

The investigations take in the high and the low, London clubland and London gangland. The latter is in the person of Jakey Solomon, a fictional rendering of the real-life gangster Jack Cohen (who also appears, incidentally, as Zack Caplan, in my own A Death in the Afternoon). The cases touch upon the intricacies of war-time relations with the Americans and MI5, especially when an international aspect is discovered. Soon, however, Merlin is inexorably led towards the upper echelons of British society, the Army and the Navy. Ellis is very strong on the British class system, its internal gradations and marital arrangements and how these dovetail with the services during wartime.

Very evocative of the times, Death is above all an intricate whodunnit, the plot strands weave though and around each other, drawing in a colourful, well-drawn cast of characters. Never short of revelations, the pacing is, nonetheless, gradual, as both investigations progress and become intertwined. The final resolution is very satisfying. A postscript reveals how justice is eventually served, sometimes in court, sometimes by the only way out.

Finally, The Cambridge Siren by Jim Kelly (Allison & Busby, £9.99). As the title suggests this is set in war-time Cambridge, a strange city when denuded of its student population, its colleges standing empty or used for war-time research. Kelly, like Lloyd with Paris, or Ellis with London, clearly knows this cityscape like the back of his hand. His ’tec is Detective Inspector Eden Brooke, as with Eddie Giral, a survivor of World War One, albeit with permanently damaged eyesight. So, he must wear heavily tinted spectacles and prefers the hours of darkness. This different way of seeing is a metaphor for Brooke’s investigative thinking as well as requiring him to be a ‘nighthawk’ and the series is called the Nighthawk series.

Finally, The Cambridge Siren by Jim Kelly (Allison & Busby, £9.99). As the title suggests this is set in war-time Cambridge, a strange city when denuded of its student population, its colleges standing empty or used for war-time research. Kelly, like Lloyd with Paris, or Ellis with London, clearly knows this cityscape like the back of his hand. His ’tec is Detective Inspector Eden Brooke, as with Eddie Giral, a survivor of World War One, albeit with permanently damaged eyesight. So, he must wear heavily tinted spectacles and prefers the hours of darkness. This different way of seeing is a metaphor for Brooke’s investigative thinking as well as requiring him to be a ‘nighthawk’ and the series is called the Nighthawk series.

Brooke is a family man and it is his son-in-law, a serving submariner, who first identifies a crime, when he’s asked to fix an apparently faulty periscope. It has been deliberately sabotaged and the factory it was made in is in Cambridge. There is also a mysterious death to deal with, the apparent suicide of a man found in an air-raid shelter. A man with a tropical suntan and Brooke’s telephone number written upon his hand.

The crimes in Siren are distinctly war-time crimes, when greedy, venal and ambitious people seek to exploit the wartime situation to their advantage. It features a ‘funk hole’, where those who are not fighting retire to the countryside and avoid the war in relative luxury, various war-time scams and some deadly crimes, including a, real, Cambridge science project. Brooke and his trusty, if depleted band of coppers at the Borough handle them all and this gives the book a much more ‘small town’, feel when compared to my other two, capital city based, recommendations.

Three wartime books set in three, very different, locations: all gripping and immersive. Put your feet up in front of the fire while the rain pours down and enjoy.

This review first appeared in Time and Leisure Magazine. Since it was written Death of an Officer by Mark Ellis has won the inaugural Cob and Pen Award at Bloody Barnes Book Festival.

This year saw a unique collaboration for me, with St Paul’s Opera Company, on their production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore (The Elixir of Love). The Director, Eloise Lally, wanted to set her version of the opera in a hospital immediately post-World War two and Patricia Ninian, SPO founder and Director had read my books The Midnight Man and A Death in the Afternoon, which are set in the South London Hospital for Women and Children. So Tricia approached me to see if using that setting might work. I was sure it would.

This year saw a unique collaboration for me, with St Paul’s Opera Company, on their production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore (The Elixir of Love). The Director, Eloise Lally, wanted to set her version of the opera in a hospital immediately post-World War two and Patricia Ninian, SPO founder and Director had read my books The Midnight Man and A Death in the Afternoon, which are set in the South London Hospital for Women and Children. So Tricia approached me to see if using that setting might work. I was sure it would. in time when men were returning home from the war to take up the jobs and roles they had left behind, which had, in their absence, been done by women. Not all the women, especially the younger ones, wanted to return to a purely domestic sphere, but they had little choice. At the South London, however, the opposite was happening. Male medics and staff were leaving, to be replaced by women and male patients were also being excluded. This unique point of tension informed my books and would inform the opera.

in time when men were returning home from the war to take up the jobs and roles they had left behind, which had, in their absence, been done by women. Not all the women, especially the younger ones, wanted to return to a purely domestic sphere, but they had little choice. At the South London, however, the opposite was happening. Male medics and staff were leaving, to be replaced by women and male patients were also being excluded. This unique point of tension informed my books and would inform the opera. Dulcamara, the quack doctor who regularly sells his ‘elixir’ for a one-time-only, knock-down price, has also returned from the war, hoping to wheedle his way in to the SLH, but Adina sends him on his way. Belcore, the Sergeant, (sung by Ted Day, see left, in rehearsal) is a long term patient, who believes the war is ongoing and marshalls his ‘troops’ of other patients, many of them wounded servicemen.

Dulcamara, the quack doctor who regularly sells his ‘elixir’ for a one-time-only, knock-down price, has also returned from the war, hoping to wheedle his way in to the SLH, but Adina sends him on his way. Belcore, the Sergeant, (sung by Ted Day, see left, in rehearsal) is a long term patient, who believes the war is ongoing and marshalls his ‘troops’ of other patients, many of them wounded servicemen.  small exhibition about the South London, using documents and memorabilia lent to us by Dr Juliet Boyd, former anaesthetist at the hospital and its unofficial archivist. This included everything from an annual report from 1917, showing the medical officers in post (all female – the only male name is that of a chaplain) to protest badges against the closure of the hospital almost seventy years later. The banners (right, with SPO Director, Patricia Ninian) produced by the opera company would be used as information at each of the performances.

small exhibition about the South London, using documents and memorabilia lent to us by Dr Juliet Boyd, former anaesthetist at the hospital and its unofficial archivist. This included everything from an annual report from 1917, showing the medical officers in post (all female – the only male name is that of a chaplain) to protest badges against the closure of the hospital almost seventy years later. The banners (right, with SPO Director, Patricia Ninian) produced by the opera company would be used as information at each of the performances.

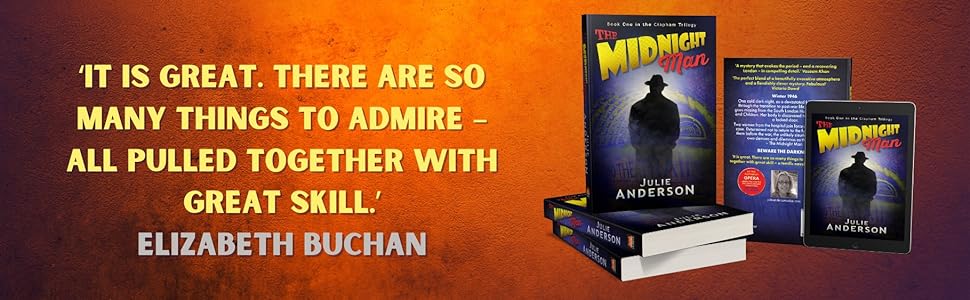

Only three weeks to go before my next book is published (by Hobeck Books) and I’ve received some very complimentary comments from fellow authors who have read proofs, like Vaseem Khan (award-winning author of the Malabar House series, set in 1950s India), Victoria Dowd (award-winning author of the Smart Woman series) and Elizabeth Buchan (multi-award winner and fellow south Londoner ). This is the enjoyable time, the pleasant anticipation, the dream of a best-seller, unsullied by one star reviews or poor sales numbers.

Only three weeks to go before my next book is published (by Hobeck Books) and I’ve received some very complimentary comments from fellow authors who have read proofs, like Vaseem Khan (award-winning author of the Malabar House series, set in 1950s India), Victoria Dowd (award-winning author of the Smart Woman series) and Elizabeth Buchan (multi-award winner and fellow south Londoner ). This is the enjoyable time, the pleasant anticipation, the dream of a best-seller, unsullied by one star reviews or poor sales numbers. so I’ll be speaking at the Clapham Society and local libraries and book clubs. Some are London wide – the London Transport Museum is carrying the book in its shop and I’ll be working with them to be part of their events calendar. Some are national – so I’ll be part of the Royal College of Nursing’s Summer exhibition and events programme, which is taking place across the country. I’m looking forward to attending its launch on 10th May (see above).

so I’ll be speaking at the Clapham Society and local libraries and book clubs. Some are London wide – the London Transport Museum is carrying the book in its shop and I’ll be working with them to be part of their events calendar. Some are national – so I’ll be part of the Royal College of Nursing’s Summer exhibition and events programme, which is taking place across the country. I’m looking forward to attending its launch on 10th May (see above). not a medic, though she worked for the RCN; a third generation involvement with nursing and medicine, albeit in a different capacity to her surgeon great grandmother. She told me lots of stories about Maud, known by the family as ‘Aunt Mary’ and sent me a photograph of her portrait, which currently hangs in Antonia’s mother’s house in London.

not a medic, though she worked for the RCN; a third generation involvement with nursing and medicine, albeit in a different capacity to her surgeon great grandmother. She told me lots of stories about Maud, known by the family as ‘Aunt Mary’ and sent me a photograph of her portrait, which currently hangs in Antonia’s mother’s house in London. I don’t know the answer to that and neither did Antonia. I hope to be able to speak with her father, who has a fund of stories about ‘Aunt Mary’ which might be enlightening. Nonetheless, I like to think that Maud, who had probably developed something of a thick skin by this time – she was denounced from the pulpit by her minister father (he said he would rather she died than became a doctor) when she was younger and had to blaze trails in other ways, decided, rather like Groucho Marx, not to join any club which would have her as a member, especially one which, in years previously, would not admit her.

I don’t know the answer to that and neither did Antonia. I hope to be able to speak with her father, who has a fund of stories about ‘Aunt Mary’ which might be enlightening. Nonetheless, I like to think that Maud, who had probably developed something of a thick skin by this time – she was denounced from the pulpit by her minister father (he said he would rather she died than became a doctor) when she was younger and had to blaze trails in other ways, decided, rather like Groucho Marx, not to join any club which would have her as a member, especially one which, in years previously, would not admit her. This is not the only remarkable coincidence attaching to this book. Early in the writing process, at first draft stage, I received an unanticipated invitation to a birthday celebration for a friend and couldn’t (for reasons too tedious to go into here) buy a birthday gift in time. So my gift was to name a character after my friend in the new book. I duly did so and, just prior to final editing, I sent her a copy of the manuscript. If she hadn’t liked ‘her’ character, or had had second thoughts about my using her name, she could withdraw and I would change the name. She and her partner, who also had a named character, were very happy, though she responded by sending me a copy of the birth certificate of her first born son. He was born at the South London Hospital in the 1970s! She had never mentioned where he was born (he now lives in Canada) so I had no idea. Thus, I found, my friend was a real patient at the real hospital as well as being a ‘character’ in the fictional version. What are the chances of that?

This is not the only remarkable coincidence attaching to this book. Early in the writing process, at first draft stage, I received an unanticipated invitation to a birthday celebration for a friend and couldn’t (for reasons too tedious to go into here) buy a birthday gift in time. So my gift was to name a character after my friend in the new book. I duly did so and, just prior to final editing, I sent her a copy of the manuscript. If she hadn’t liked ‘her’ character, or had had second thoughts about my using her name, she could withdraw and I would change the name. She and her partner, who also had a named character, were very happy, though she responded by sending me a copy of the birth certificate of her first born son. He was born at the South London Hospital in the 1970s! She had never mentioned where he was born (he now lives in Canada) so I had no idea. Thus, I found, my friend was a real patient at the real hospital as well as being a ‘character’ in the fictional version. What are the chances of that? Two happy accidents; I hope they bode well for the book. ‘The Midnight Man’ is published by Hobeck Books on 30th April. I will be posting further pieces about it as the date approaches. Available for pre-order from Mr Besos’

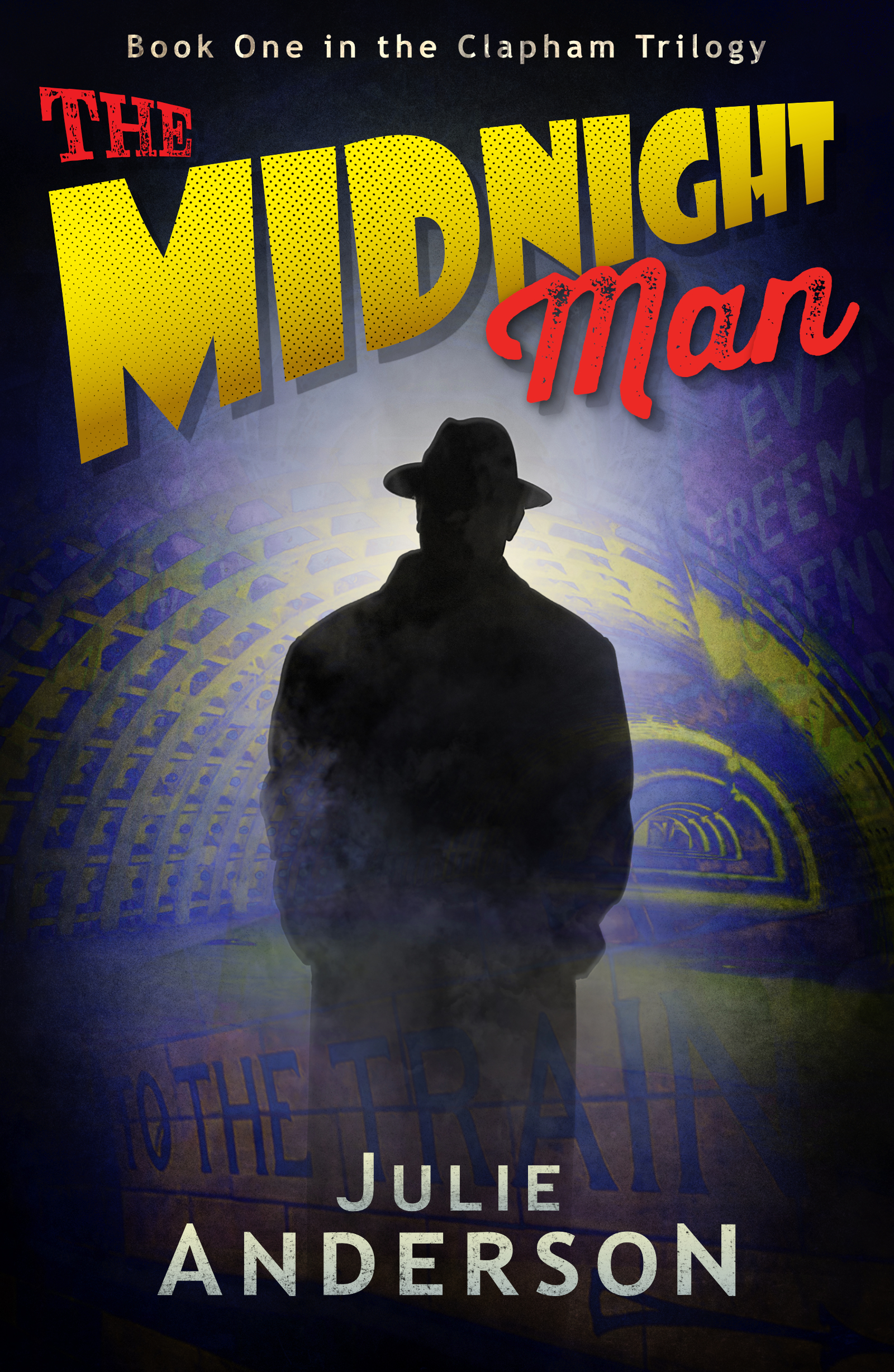

Two happy accidents; I hope they bode well for the book. ‘The Midnight Man’ is published by Hobeck Books on 30th April. I will be posting further pieces about it as the date approaches. Available for pre-order from Mr Besos’  I am very pleased with the cover of my next novel, The Midnight Man. Created by graphic designer,

I am very pleased with the cover of my next novel, The Midnight Man. Created by graphic designer,

hereby hangs another tale, which I will doubtless return to.

hereby hangs another tale, which I will doubtless return to. Clapham Common, clustered around Clapham South Underground station. Some of these places are highly unusual, some still exist (although they have been repurposed) and others can be visited today.

Clapham Common, clustered around Clapham South Underground station. Some of these places are highly unusual, some still exist (although they have been repurposed) and others can be visited today. large donation which, some speculated, came from a female member of the royal family, they collected enough to found the South London Hospital for Women and Children. At first the hospital operated in two large houses near Clapham South tube station, but, in 1916, Queen Mary opened a purpose-built eighty bed hospital, the largest women’s general hospital in the UK.

large donation which, some speculated, came from a female member of the royal family, they collected enough to found the South London Hospital for Women and Children. At first the hospital operated in two large houses near Clapham South tube station, but, in 1916, Queen Mary opened a purpose-built eighty bed hospital, the largest women’s general hospital in the UK. fondly remembered the ‘South London’ or ‘SLH’. There is even a Facebook group, to which I now belong, entitled South London Women’s Hospital occupation 1984─85 where those who protested at the time, many of them staff and patients, reminisce and organize the occasional get together. So, there was a certain amount of pressure to get it right.

fondly remembered the ‘South London’ or ‘SLH’. There is even a Facebook group, to which I now belong, entitled South London Women’s Hospital occupation 1984─85 where those who protested at the time, many of them staff and patients, reminisce and organize the occasional get together. So, there was a certain amount of pressure to get it right. good location for my book, enabling me to show changes taking place. Then I found out about the South London Hospital for Women & Children. Clapham has been my home for over thirty years and I used to walk past the empty hospital buildings on my way to and from the tube every day, but I knew little about it. When I began researching, I discovered that it was the largest woman-only hospital in the UK, run exclusively by and for women. This made it both unusual and very apposite for my book.

good location for my book, enabling me to show changes taking place. Then I found out about the South London Hospital for Women & Children. Clapham has been my home for over thirty years and I used to walk past the empty hospital buildings on my way to and from the tube every day, but I knew little about it. When I began researching, I discovered that it was the largest woman-only hospital in the UK, run exclusively by and for women. This made it both unusual and very apposite for my book. the early hospital. I also spoke with a former midwife and former nurses, all of whom fondly remembered the hospital. There is a Facebook group, to which I now belong, called South London Women’s Hospital occupation 1984─85 where those who protested at the hospital’s closure, many of them staff and patients, reminisce and organize the occasional get together.

the early hospital. I also spoke with a former midwife and former nurses, all of whom fondly remembered the hospital. There is a Facebook group, to which I now belong, called South London Women’s Hospital occupation 1984─85 where those who protested at the hospital’s closure, many of them staff and patients, reminisce and organize the occasional get together. architect’s plans. I also read minutes of meetings of the South London’s management board and similar minutes belonging to other hospitals of the time and this helped to give me an understanding of the context. It is instructive that, despite there being an acute shortage of nurses after the war, the SLH never had a problem attracting nurses; it was a place where women wanted to work.

architect’s plans. I also read minutes of meetings of the South London’s management board and similar minutes belonging to other hospitals of the time and this helped to give me an understanding of the context. It is instructive that, despite there being an acute shortage of nurses after the war, the SLH never had a problem attracting nurses; it was a place where women wanted to work. Clapham South underground station onto Clapham Common Southside, about a hundred yards away you’ll see a concrete pillbox of a building, on the common very close to the busy road. Currently graffiti covered, this unlovely and unloved building is the entrance to a fascinating world beneath the ground.

Clapham South underground station onto Clapham Common Southside, about a hundred yards away you’ll see a concrete pillbox of a building, on the common very close to the busy road. Currently graffiti covered, this unlovely and unloved building is the entrance to a fascinating world beneath the ground. rockets bombarded London. South Londoners descended, nightly, in the lifts, to their bunk space in the shelter, which held canteens, lavatories, washrooms and a medical centre. Apparently, it was quite sociable, people played music, sang songs and played cards and other games as the rockets fell overhead. All this while the underground trains rumbled above them, the shelters being deeper even than the underground lines.

rockets bombarded London. South Londoners descended, nightly, in the lifts, to their bunk space in the shelter, which held canteens, lavatories, washrooms and a medical centre. Apparently, it was quite sociable, people played music, sang songs and played cards and other games as the rockets fell overhead. All this while the underground trains rumbled above them, the shelters being deeper even than the underground lines. unusual one ( I’ll be blogging about it as publication day approaches ). Some of its buildings still stand, near Clapham South Underground station as the photograph (right) shows. This was the ‘New Wing’ erected in the 1930s. It is now an apartment building, above a supermarket ( the entrance to which can just be seen on the far left).

unusual one ( I’ll be blogging about it as publication day approaches ). Some of its buildings still stand, near Clapham South Underground station as the photograph (right) shows. This was the ‘New Wing’ erected in the 1930s. It is now an apartment building, above a supermarket ( the entrance to which can just be seen on the far left).

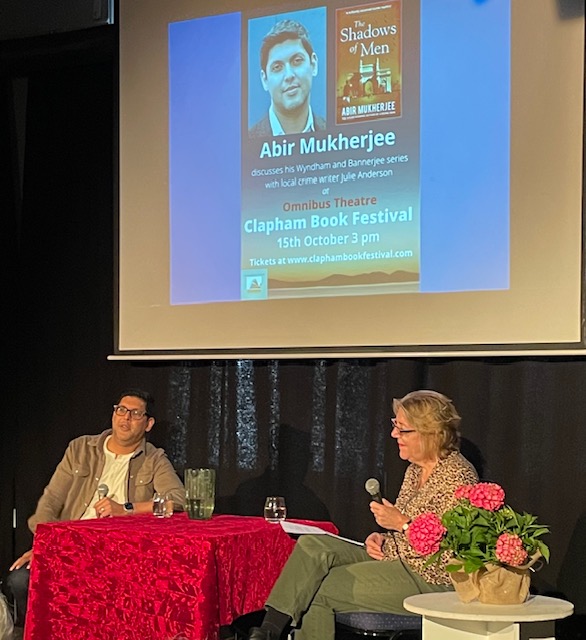

The 2022 Clapham Book Festival is all but over. It began on a gloriously sunny autumn day on 9th October, walking around the Common on the Literary Trail, something which was repeated this Saturday last. It was a lovely day again, but, as the walk neared its end, the sky grew black. People dispersed and I headed for home to change for my afternoon session when the heavens opened. I got soaked through.

The 2022 Clapham Book Festival is all but over. It began on a gloriously sunny autumn day on 9th October, walking around the Common on the Literary Trail, something which was repeated this Saturday last. It was a lovely day again, but, as the walk neared its end, the sky grew black. People dispersed and I headed for home to change for my afternoon session when the heavens opened. I got soaked through. tremendous, a joy to interview, in that he has a huge fund of anecdotes and amusing tales which makes life very easy for the interviewer. He grew up in Hamilton, just outside Glasgow to Bengali parents and talked about schooldays tribalism – ‘Are you a Catholic or a Protestant?’ ‘I’m a Hindu.’ Silence, followed by, ‘Yes, but are you a Catholic Hindu or a Protestant Hindu?’. The hour flew by and there was little time for questions, but everyone was entertained and impressed. The books practically flew off the counter, all signed by Abir.

tremendous, a joy to interview, in that he has a huge fund of anecdotes and amusing tales which makes life very easy for the interviewer. He grew up in Hamilton, just outside Glasgow to Bengali parents and talked about schooldays tribalism – ‘Are you a Catholic or a Protestant?’ ‘I’m a Hindu.’ Silence, followed by, ‘Yes, but are you a Catholic Hindu or a Protestant Hindu?’. The hour flew by and there was little time for questions, but everyone was entertained and impressed. The books practically flew off the counter, all signed by Abir. The cafe/bar at Omnibus had been packed all afternoon, not just with Festival goers, but also a ‘New Mums n’ Dads’ club meeting, but this ended by about five thirty, which was a relief, as we knew we had a completely full house that evening for Sir Antony Beevor and Dr Piers Brendon. The Cafe/bar is a super space, but it would be creaking at the seams with eighty Festival folk, let alone the new parents. We need not have worried. Although crowded, this leant the whole evening an excited buzz.

The cafe/bar at Omnibus had been packed all afternoon, not just with Festival goers, but also a ‘New Mums n’ Dads’ club meeting, but this ended by about five thirty, which was a relief, as we knew we had a completely full house that evening for Sir Antony Beevor and Dr Piers Brendon. The Cafe/bar is a super space, but it would be creaking at the seams with eighty Festival folk, let alone the new parents. We need not have worried. Although crowded, this leant the whole evening an excited buzz. win the Russian Civil War? What did he think would happen in Ukraine? Why was the Russian Civil War so full of atrocities and were we seeing a repetition in Ukraine? The hour, as with Abir Mukherjee, flew past, though for different reasons, this was intellectual engagement of a high order. Afterwards the queue for both presenters was long, with people anxious to get their books signed before the evening closed.

win the Russian Civil War? What did he think would happen in Ukraine? Why was the Russian Civil War so full of atrocities and were we seeing a repetition in Ukraine? The hour, as with Abir Mukherjee, flew past, though for different reasons, this was intellectual engagement of a high order. Afterwards the queue for both presenters was long, with people anxious to get their books signed before the evening closed. Hosted by Lucy Kane from media partners

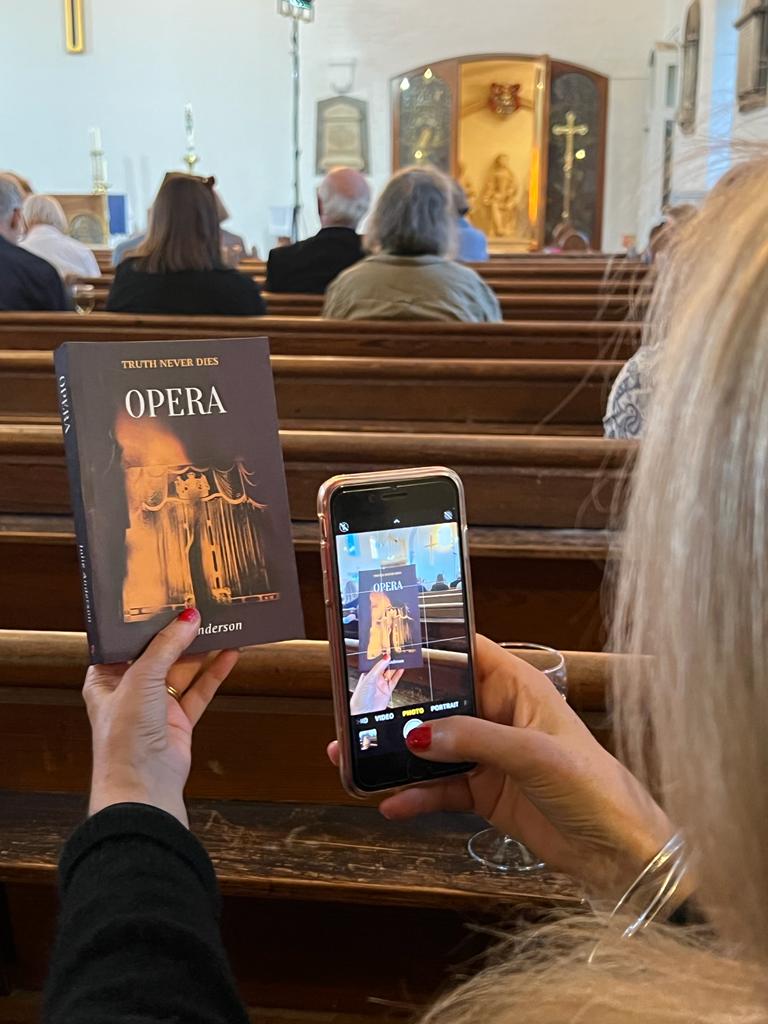

Hosted by Lucy Kane from media partners  The low, autumnal sunlight slanted across the churchyard of St Paul’s Church in Clapham on a beautiful September evening one week ago. Cars drew up to the church’s railings, people walked down the winding path to the heavy church doors and inside there was a buzz of anticipation of good entertainment to come. They were there to celebrate the launch of ‘Opera‘ the third in the Cassandra Fortune series of murder mysteries, together with the music of Puccini and Tosca in particular (the opera in ‘Opera‘). I was at the door to greet them.

The low, autumnal sunlight slanted across the churchyard of St Paul’s Church in Clapham on a beautiful September evening one week ago. Cars drew up to the church’s railings, people walked down the winding path to the heavy church doors and inside there was a buzz of anticipation of good entertainment to come. They were there to celebrate the launch of ‘Opera‘ the third in the Cassandra Fortune series of murder mysteries, together with the music of Puccini and Tosca in particular (the opera in ‘Opera‘). I was at the door to greet them. evening’s entertainment), the sound system was set up, the bar was stocked, staffed and ready to dispense and the Claret Press table was ready with signed books for sale. Programmes were handed out at the door. The church filled, gradually, with local friends, of the author or of the opera company, and with those from farther afield who had come to help celebrate. About a third of the crowd were probably also writers, many of them writers of crime fiction (see Anne Coates, author of the Hannah Weybridge mysteries, with Katie Isbester of Claret Press and myself, right). Other Claret authors, Steve Sheppard and Sylvia Vetta were there as well as reknown Clapham authors like Elizabeth Buchan. Clapham Book Festival friends were out in force, as were the members of the Clapham Writers Circle. In total there were between seventy and eight people in the beautiful church.

evening’s entertainment), the sound system was set up, the bar was stocked, staffed and ready to dispense and the Claret Press table was ready with signed books for sale. Programmes were handed out at the door. The church filled, gradually, with local friends, of the author or of the opera company, and with those from farther afield who had come to help celebrate. About a third of the crowd were probably also writers, many of them writers of crime fiction (see Anne Coates, author of the Hannah Weybridge mysteries, with Katie Isbester of Claret Press and myself, right). Other Claret authors, Steve Sheppard and Sylvia Vetta were there as well as reknown Clapham authors like Elizabeth Buchan. Clapham Book Festival friends were out in force, as were the members of the Clapham Writers Circle. In total there were between seventy and eight people in the beautiful church.

Grand opera is always intense and these two arias especially so, so a lightening of the mood was required before the interval. This was provided by an ‘interruption’ by a police constable, PC Willis, who had just arrived from the Houses of Parliament (although dressed in pink). Bass baritone Masimba Ushe delivered the sentry’s song from Gilbert & Sullivan’s Iolanthe ‘When all night long, a chap remains…’ in sonorous and amusing fashion. Laughter heralded the interval, when everyone headed to the bar (where the barkeepers were kept very busy).

Grand opera is always intense and these two arias especially so, so a lightening of the mood was required before the interval. This was provided by an ‘interruption’ by a police constable, PC Willis, who had just arrived from the Houses of Parliament (although dressed in pink). Bass baritone Masimba Ushe delivered the sentry’s song from Gilbert & Sullivan’s Iolanthe ‘When all night long, a chap remains…’ in sonorous and amusing fashion. Laughter heralded the interval, when everyone headed to the bar (where the barkeepers were kept very busy). beforehand and I kept my answers short (as she had told me to, I tend to ramble). People seemed to enjoy it and, after questions from the floor, we ended to loud applause.

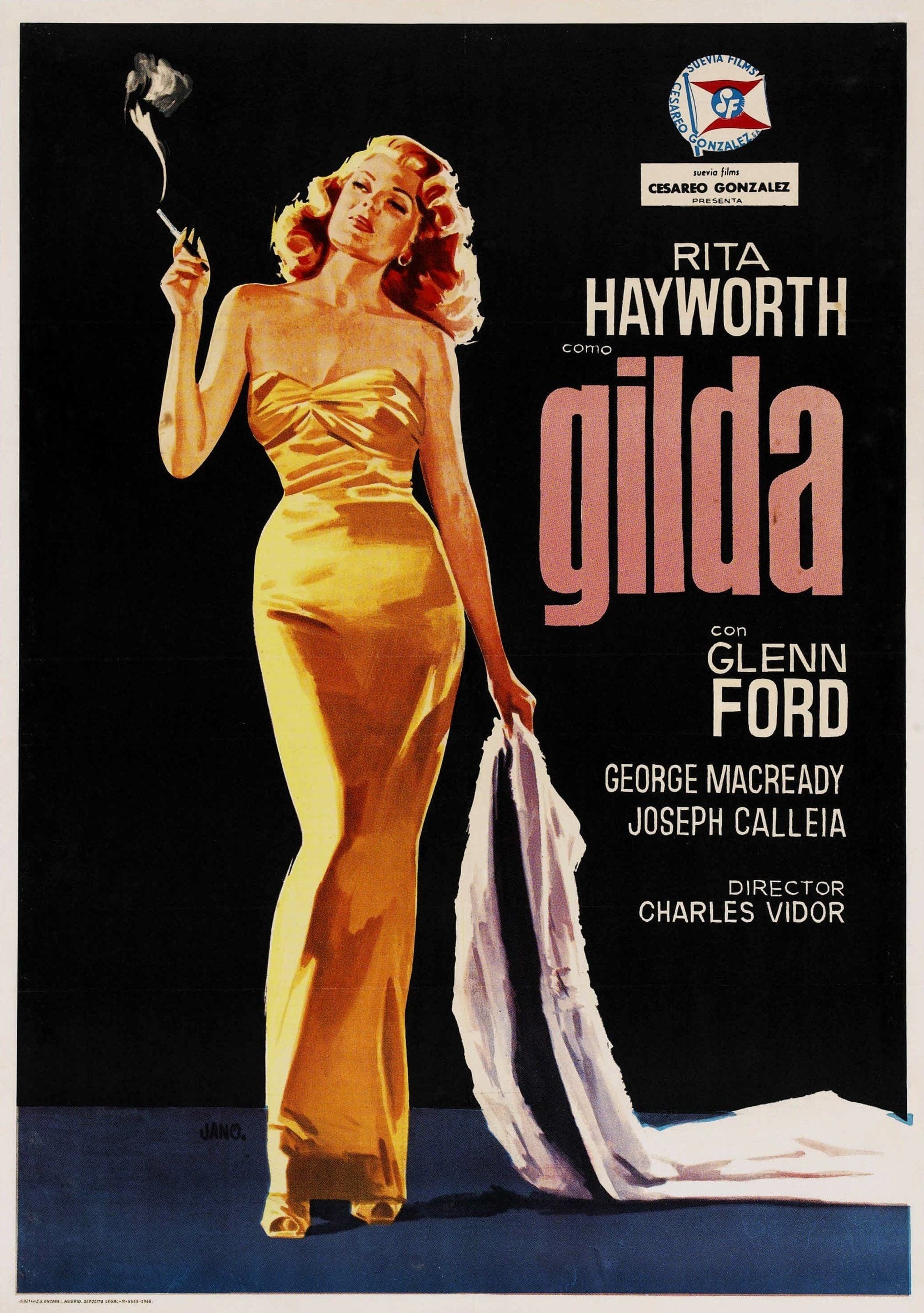

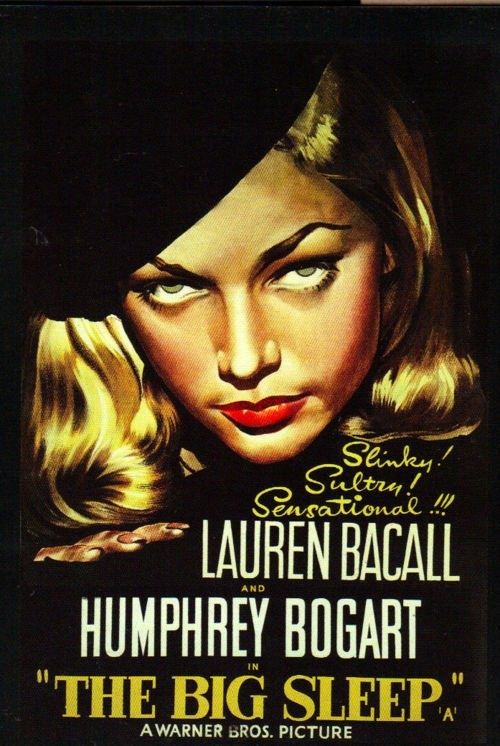

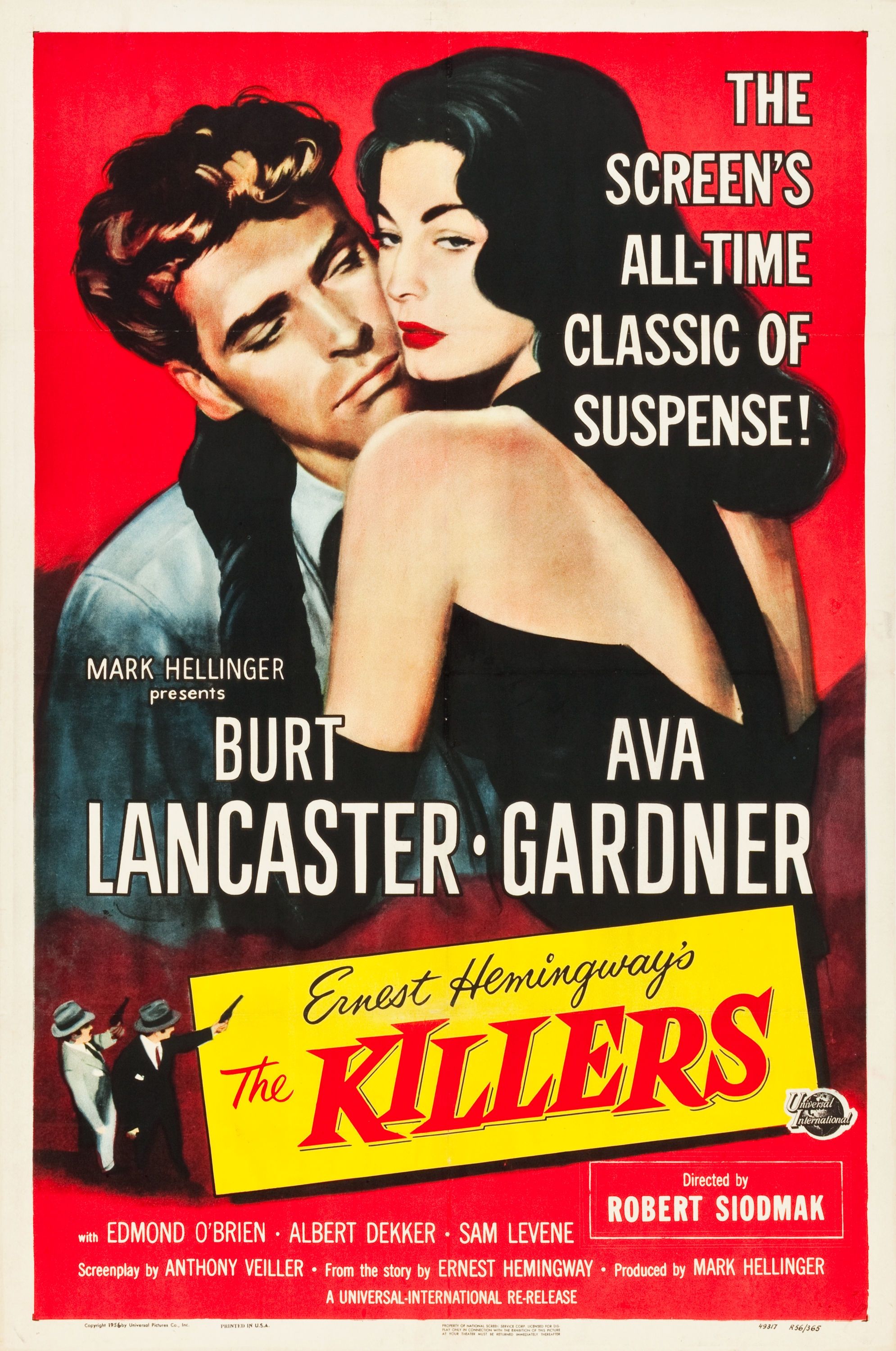

beforehand and I kept my answers short (as she had told me to, I tend to ramble). People seemed to enjoy it and, after questions from the floor, we ended to loud applause. bunting made of the posters and other images of Tosca which I had been collecting for months before the book was published.

bunting made of the posters and other images of Tosca which I had been collecting for months before the book was published. Ninian and the singers of St Paul’s Opera, which made it unique. Many of those who attended spoke or wrote to me, telling me how much they enjoyed it. Plus, my publisher sold lots of my books. It was a spectacular way to launch a title and a very special occasion.

Ninian and the singers of St Paul’s Opera, which made it unique. Many of those who attended spoke or wrote to me, telling me how much they enjoyed it. Plus, my publisher sold lots of my books. It was a spectacular way to launch a title and a very special occasion.