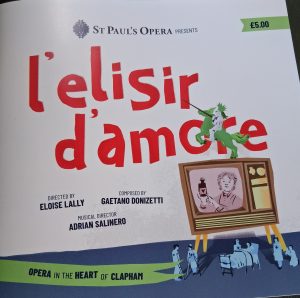

Earlier this year I was approached by Patricia Ninian of St Paul’s Opera company with the suggestion that I should work with them on their summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore by Donizetti. The director, Eloise Lally (English Touring Opera) wanted to set the production in a hospital after the second world war. Patricia had read my book, The Midnight Man and spotted the synergies immediately, especially as ‘my’ hospital was based on a real, Clapham hospital – the South London Hospital for Women and Children. I was invited to rehearsals and I began to keep a rehearsal diary, a version of which follows.

Earlier this year I was approached by Patricia Ninian of St Paul’s Opera company with the suggestion that I should work with them on their summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore by Donizetti. The director, Eloise Lally (English Touring Opera) wanted to set the production in a hospital after the second world war. Patricia had read my book, The Midnight Man and spotted the synergies immediately, especially as ‘my’ hospital was based on a real, Clapham hospital – the South London Hospital for Women and Children. I was invited to rehearsals and I began to keep a rehearsal diary, a version of which follows.

Saturday 17th May

It’s the first full day of rehearsals and Eloise Lally, the Director, sits in a front pew blocking out stage positions and movement for the chorus. Most members of the chorus are here, taking up their places and moving at the direction of Eloise. Outside the sky is blue. Sunshine makes angular shadows on the deep window embrasures.

It’s obvious that there’s been previous discussions about the setting – in the South London Hospital, Clapham during the period following the end of World War two – and its fruits are evident.

‘Is this where the bed will be?’ asks a chorus member.

‘You’re sitting on it,’ responds Eloise.

The stage is bare.

Yet there is also a television, a relative rarity in late 1940s London, but certainly possible in a hospital common room. Chorus members stare at the invisible item, transfixed by its novelty.

Individual chorus members already have characters. So, I meet Pam, a south London girl, with the accent on ‘sarf’. A middle-aged lady with lumbago, she is never seen without a cigarette in her fingers. Many chorus members are halt and lame, patients of the hospital and walking wounded. These ‘characters’ give both variation and verisimilitude to what would otherwise simply be an amorphous group.

on ‘sarf’. A middle-aged lady with lumbago, she is never seen without a cigarette in her fingers. Many chorus members are halt and lame, patients of the hospital and walking wounded. These ‘characters’ give both variation and verisimilitude to what would otherwise simply be an amorphous group.

Eloise doesn’t only place the chorus physically, but also psychologically. She tells us that all the chorus characters know that Nemorino is hopelessly in love with Adina, who is so far out of his reach. Most of them feel sorry for him. They see, at the beginning of Act 2, that the lovelorn suitor buys something from Dr Dulcamara and are curious about what. Hospitals are places where gossip and rumour often run unchecked and L’Elisir’s South London is no different.

Throughout the pianist plays and replays accompaniment and also sings the soloists parts where necessary sometimes to the amusement of the cast. She is aided in the tenor role by Edvard Adde (the Norwegian tenor, cover for the role of Nemorino).

Throughout the pianist plays and replays accompaniment and also sings the soloists parts where necessary sometimes to the amusement of the cast. She is aided in the tenor role by Edvard Adde (the Norwegian tenor, cover for the role of Nemorino).

At two o’clock we break for lunch and many of the singers head towards Clapham Common and the crowds who are enjoying the weekend sunshine, while others remain closer by in the dappled shade of the peaceful churchyard. Back to resume at three!

Saturday 24th May

It is one week and several rehearsals on and there are more singers in a rather chilly church. This time the chorus and three of the principals are here, as is the Director of Music, Adrian Salinero at the piano, as well as Eloise. Outside the sky is grey.

We go ‘from the top’ Act I, Scene I and singers enter from different parts of the church to take their places on stage. Chorus members ‘characters’ do their stage business and eventually settle down to watch the new-fangled television. Matron Adina (Dorset-born soprano, Fiona Hymns) consults with Nurse Gianetta (Isabella Roberts), then it’s straight into her first aria.

new-fangled television. Matron Adina (Dorset-born soprano, Fiona Hymns) consults with Nurse Gianetta (Isabella Roberts), then it’s straight into her first aria.

The interplay between principals and with other cast members is taking shape. Belcore (baritone, Theodore ‘Ted’ Day) is a delusional patient who imagines he is still fighting the war, he treats everyone as if they’re in his military company and the rest of the cast plays along with tolerant affection. He preens himself in preparation for his declaration of love for Adina. Her exasperated astonishment, when he makes it, is very funny, without being in any way cruel. I laughed aloud.

Dr Dulcamara (Essex-born baritone Ashley Mercer) makes a dramatic entrance and begins his spiel, producing all manner of ‘wonders’ from his capacious bag and offering, at a one-time-only knock-down price, his miracle wonder cure for all ailments.

The chorus is impressed. Matron Adina is not. The rehearsal ends with their mini-confrontation.

Eloise calls the singers together and gives them notes, about movement, stage business and psychology. The chorus are to remain still and rapt as Matron Adina sings her aria. She is most definitely in charge, but she is also their healer, so they are both overawed and grateful. Belcore is too static, holding his rose for Adina and should make more of his preparation. The relationship between Adina and Dulcamara needs more definition.

Eloise calls the singers together and gives them notes, about movement, stage business and psychology. The chorus are to remain still and rapt as Matron Adina sings her aria. She is most definitely in charge, but she is also their healer, so they are both overawed and grateful. Belcore is too static, holding his rose for Adina and should make more of his preparation. The relationship between Adina and Dulcamara needs more definition.

Through-out Adrian insists that the singers keep tempo and, occasionally, gives notes of his own, mainly to the chorus.

In the lunch break I meet a few more of the chorus members’ characters; there’s Charles, a professional military man wounded in the war, hitching up his trousers when he sits – ramrod straight despite his damaged leg – to avoid stretching their fabric. Luigi, an Italian wounded in the Great War fighting Britain, who came to Clapham following the Londoner nurse who tended him and who is now a stalwart member of the community. He sells newspapers just outside the hospital.

Then it’s back to the South London Hospital to take it ‘from the top’ again.

Tuesday 10th June

It’s an evening rehearsal at St Paul’s and low sun shines in through windows on the opposite side of the church. Eloise makes tea and Adrian is at the piano, as two soloists, Latvian tenor Martins Smaukstelis (Nemorino) and Ashley Mercer (Dr Dulcamara) arrive. They will concentrate on their duet scene in Act One, in which the crafty doctor sells the naïve Nemorino his ‘elixir of love’.

There is a sing through first and male voices echo around the church. Then a quick discussion with Adrian.

There is a sing through first and male voices echo around the church. Then a quick discussion with Adrian.

‘Shall we?’ says Eloise.

The soloists take up positions.

Nemorino approaches Dulcamara with a mixture of desperate hope, excitement and fear. Can this ‘alchemist’ help him win Adina? Dulcamara cannot believe his luck and quickly rips a label from a bottle of red wine, offering it as the famed elixir for all the money in Nemorino’s pockets. The doctor rolls his eyes at the audience, who are complicit in his ruse. Then he wants to get away before his victim twigs, but Nemorino calls him back. How does he use the elixir?

There follows a very funny scene in which the doctor instructs Nemorino in how to open a bottle of wine. This scene is, as Eloise says, ‘all about the bench’, where the two characters sit and most of their interaction happens.

As I watch another kind of alchemy takes place.

Eloise offers suggestions but allows her soloists room to create. These two are almost affectionate, she suggests, they like each other. The doctor invites Nemorino to sit, his gestures and instructions become fatherly in tone. Nemorino is trusting, child-like. The action emerges, through physical gesture as much as song, the singers acting and interacting spontaneously.

Nemorino’s tigerish enthusiasm bubbles over and he starts to rush away, to share his good fortune. Dulcamara realises that if other learn of this, the game will be up, his trickery exposed, so he calls Nemorino back to persuade him to keep the elixir secret. The scene ends in more subdued fashion, as Nemorino is, as Eloise says ‘looking inward’. The tone changes.

We run through again, this time in full voice. Stage action now fits seamlessly to the music – when Nemorino plucks up courage to approach Dulcamara there is what Eloise describes as ‘walking music’ and that’s exactly what it sounds like. The handshake between the two men comes at the climax of a passage of music, carrying over to signal in sound what Dulcamara signals physically – that he cannot extricate his hand from Nemorino’s grateful grasp.

Doubtless there will be refinement, but a scene, musically and emotionally consistent, dramatic and very funny, has come into being where none existed before.

This is alchemy indeed.

Tuesday 17th June

The church is bathed in soft evening light and the whole of the cast is here. So is David Butt Phillip, international opera star and patron of St Paul’s Opera, so the church pews are dotted with a select audience, the VIP Friends of SPO. This is the first time David has seen this developing production. Adrian is at the piano and Eloise is in her customary place.

audience, the VIP Friends of SPO. This is the first time David has seen this developing production. Adrian is at the piano and Eloise is in her customary place.

The singers, especially the soloists, are on their mettle in David’s presence and one or two show signs of nervousness. Plus, Eloise will be focusing more on the soloists this evening, she explains, so as to reinforce the emotional story-telling throughout.

We go from Adina’s first aria in Act One. David reminds the chorus that their staccato phrases towards the end of Adina’s aria should be crisp and succinct beneath the rich and soaring soprano voice, ‘half as long and half as loud’. We repeat and transition into Belcore’s ‘proposal’ aria. There is business here for Nemorino, overhearing Belcore’s declaration of love and reacting to the proposal to his beloved Adina. As Eloise and Martins consider some repositioning, David advises Ted on his stance which should be ‘less  elegant, more military, butch, showing Belcore believes that he’s ready for anything’.

elegant, more military, butch, showing Belcore believes that he’s ready for anything’.

We go again. This time Belcore’s marshalling of his ‘troop’ is more militarily done and obviously for Adina’s benefit. The chorus exits in single file, marching. David advises that, without a conductor to cue them, they have to take responsibility for getting on top of the music, thinking about what’s to come several bars in advance and attacking it ‘on point’. Otherwise the sound will be ‘mushy’.

The first duet between the romantic leads follows, but this isn’t a standard lovers’ duet, it is more complex. Eloise wants clarity of emotional story-telling and so, in the break, she discusses the duet, almost line by line with the two singers, asking each, like a therapist, to describe the feelings of their characters at that point in the aria. So, when we begin again we have flirting, devotion, apparent rejection and pleasure in each other.

And on to Dr Dulcamara’s entrance…

30th June 2025

It is the hottest day of the year so far and the interior of the church feels mercifully cool after the hard sun outside. There are quite a few folk around – a professional photographer, the light and sound technicians, various people unknown to me (donors, critics?) as well as the cast and the musicians.

It is the hottest day of the year so far and the interior of the church feels mercifully cool after the hard sun outside. There are quite a few folk around – a professional photographer, the light and sound technicians, various people unknown to me (donors, critics?) as well as the cast and the musicians.

The stage is, literally, set. It is multi-level in three main blocks and with lots of entrances and exits, perfect for lots of motion in a comedic piece. The red brick walls of the South London Hospital are to the fore, there is a hospital bed, screens, trolley and other ward paraphernalia. On the stage is an old-fashioned, wooden box TV with doors; to either side of the stage are flatscreens to carry surtitles. Strings of lights are hung across the church, they will be illuminated later as darkness falls.

Nurses in 1940/50s uniforms mingle with patients in pyjamas or nightdresses. Ashley (Dr Dulcamara) and Fiona (Adina) wait until the last minute to don their costumes, which are heavy in the heat – especially Dulcamara’s tight fitting leather aviator hat. Musicians arrive one by one and Adrian sits them in their places and begins to talk about the music, while using a bright fan as if to the manner born (he hails from the Basque country, so he probably was). The church begins to feel hotter.

Eloise is everywhere; she’s up in the balcony, checking the sightlines, on stage with Ted (Belcore) discussing how he will enlist Nemorino (by using his own medical chart) and with the cast in the Green Room.

Eloise is everywhere; she’s up in the balcony, checking the sightlines, on stage with Ted (Belcore) discussing how he will enlist Nemorino (by using his own medical chart) and with the cast in the Green Room.

The musicians are all here, so… we begin!

I have heard much of this many times before, but it seems fresh and different now. This is the added element which costumes and staging bring. They also add physical authority to the concept of setting the opera in a post-war Clapham hospital. I knew it would work, but now it seems inspired.

The Adina-Nemorino dynamic is immediate and very strong, as befits the central relationship of the story. The nurses chat and inter-react like workmates. The south Londoners add variety and colour (as well as sound). Music and voices reverberate around the church (it will be interesting to see what sort of impact a full audience will have on the sound).

The spirit of the piece is celebratory and there is a slight carnival aspect, even though it is set in a hospital. It is funny and moving and beautiful. I feel so privileged to have watched this production develop, to talk with the director and soloists and chorus members at various stages. Thank you, all of you.

L’Elisir d’Amore is going to be an enormous success.

N.B. Since this diary was written the St Paul’s Opera Summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore has been given an Assessors Award from the Offie’s which celebrate independent and fringe theatre. Watch this space for a Nomination!

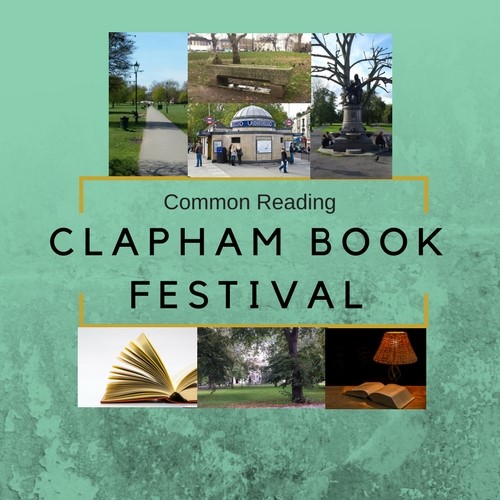

The first event of 2022’s Clapham Book Festival took place yesterday on a gloriously sunny, autumn day on Clapham Common. Starting at Omnibus Theatre on the Northside a small but determined group of walkers spent two hours discovering and discussing Clapham’s literary connections, past and present. From Roger L’Estrange, the ‘Bloodhound of the Press’ to Malorie Blackman, Children’s Laureate, via novelists, biographers, historians, poets and Nobel prize-winners we had fun seeing where they lived and worked in Clapham.

The first event of 2022’s Clapham Book Festival took place yesterday on a gloriously sunny, autumn day on Clapham Common. Starting at Omnibus Theatre on the Northside a small but determined group of walkers spent two hours discovering and discussing Clapham’s literary connections, past and present. From Roger L’Estrange, the ‘Bloodhound of the Press’ to Malorie Blackman, Children’s Laureate, via novelists, biographers, historians, poets and Nobel prize-winners we had fun seeing where they lived and worked in Clapham. Wyndham and Bannerjee series of murder mysteries set in 1920s Calcutta, which begins with ‘A Rising Man‘ and runs to the most recent, ‘The Shadows of Men‘. Our intrepid heroes navigate the slums of ‘Black Town’, the genteel villas of Alipor, Chinese opium dens, the high politics of the Lieutenant Governor’s mansion and the low machinations of the secret service. Pre-independence India’s politics, religious and secular, feature in all the books which adds to their fascination.

Wyndham and Bannerjee series of murder mysteries set in 1920s Calcutta, which begins with ‘A Rising Man‘ and runs to the most recent, ‘The Shadows of Men‘. Our intrepid heroes navigate the slums of ‘Black Town’, the genteel villas of Alipor, Chinese opium dens, the high politics of the Lieutenant Governor’s mansion and the low machinations of the secret service. Pre-independence India’s politics, religious and secular, feature in all the books which adds to their fascination. In the evening we have a real treat for history lovers and all those interested in today’s Russia and how it got to where it is now. The eminent and much garlanded Sir Antony Beevor discusses his latest book on Russia – ‘Russia: Revolution and Civil War 1917 – 1921′ – with Cambridge historian Dr Piers Brendon. Tickets for this are selling quickly, so I anticipate a full theatre and I’m not surprised, Sir Antony is always knowledgeable and insightful and Piers Brendon is the perfect person to draw out the historical parallels. Expect a treat.

In the evening we have a real treat for history lovers and all those interested in today’s Russia and how it got to where it is now. The eminent and much garlanded Sir Antony Beevor discusses his latest book on Russia – ‘Russia: Revolution and Civil War 1917 – 1921′ – with Cambridge historian Dr Piers Brendon. Tickets for this are selling quickly, so I anticipate a full theatre and I’m not surprised, Sir Antony is always knowledgeable and insightful and Piers Brendon is the perfect person to draw out the historical parallels. Expect a treat. November another online event, discussing ‘Crossed Off the Map: Travels in Bolivia’ with prize-winning travel writer Shafik Meghji. I know very little about Bolivia, so this will be new and interesting for me. Both the zoom events cost only £5.

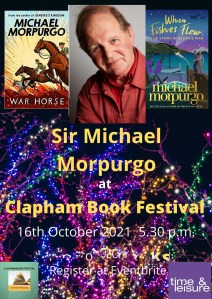

November another online event, discussing ‘Crossed Off the Map: Travels in Bolivia’ with prize-winning travel writer Shafik Meghji. I know very little about Bolivia, so this will be new and interesting for me. Both the zoom events cost only £5. Saturday’s Festival day is over. The vibe wasn’t quite as energy-filled and buzzing as usual (numbers were restricted because of COVID) but our audiences made up with enthusiasm what was lacking in terms of numbers. The children who came for Sir Michael Morpurgo were a delight and it’s probably not overdoing it to say that their attitude towards books and reading may have been changed for life by that encounter. In the evening Ed Stourton was intelligent and entertaining, taking lots of, sometimes difficult, questions about broadcasting from the audience.

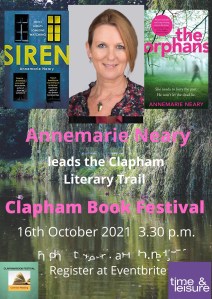

Saturday’s Festival day is over. The vibe wasn’t quite as energy-filled and buzzing as usual (numbers were restricted because of COVID) but our audiences made up with enthusiasm what was lacking in terms of numbers. The children who came for Sir Michael Morpurgo were a delight and it’s probably not overdoing it to say that their attitude towards books and reading may have been changed for life by that encounter. In the evening Ed Stourton was intelligent and entertaining, taking lots of, sometimes difficult, questions about broadcasting from the audience. Clapham writer, one Edward Winslow, who sailed on the Mayflower. My fellow guide, Irish-born award-winning writer Annemarie Neary accompanied us, at least part of the way around the Common. Her walk and mine covered some of the same ground, though she diverged to do a deep dive into the writers who lived near the Northside of the Common, while I continued with a part circumference, taking in the Southside too.

Clapham writer, one Edward Winslow, who sailed on the Mayflower. My fellow guide, Irish-born award-winning writer Annemarie Neary accompanied us, at least part of the way around the Common. Her walk and mine covered some of the same ground, though she diverged to do a deep dive into the writers who lived near the Northside of the Common, while I continued with a part circumference, taking in the Southside too. a certain Ms Rowing who acknowledges that the ‘first brick of Hogwarts’ was laid in Clapham.

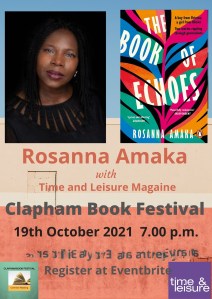

a certain Ms Rowing who acknowledges that the ‘first brick of Hogwarts’ was laid in Clapham. The feedback we received was uniformly excellent. But we still have two events to come, both via zoom and costing only £5. The first is tonight. I am speaking with Brixton resident Rosanna Amaka about her amazing debut novel ‘The Book of Echoes’ set in East London, Nigeria, the USA and Brixton’ You can buy tickets at

The feedback we received was uniformly excellent. But we still have two events to come, both via zoom and costing only £5. The first is tonight. I am speaking with Brixton resident Rosanna Amaka about her amazing debut novel ‘The Book of Echoes’ set in East London, Nigeria, the USA and Brixton’ You can buy tickets at  The research is done, the cards of notes are written and the hand-out prepared, now it’s all about the weather. My Literary Walk kicks off this year’s Festival at two o’clock on Saturday and, fingers crossed, it looks like it’s going to be dry and ( relatively ) sunny! My supplications to the weather gods are working so far. It’ll be so much better a festival if that is the case, encouraging people out onto the Common and to participate in things. Omnibus Theatre, our venue, has a pleasant terrace to its Bar/Cafe which overlooks the Common and that is a good place to sit in the sunshine. But the real impact will be on the walks, which would be so much more difficult in the rain.

The research is done, the cards of notes are written and the hand-out prepared, now it’s all about the weather. My Literary Walk kicks off this year’s Festival at two o’clock on Saturday and, fingers crossed, it looks like it’s going to be dry and ( relatively ) sunny! My supplications to the weather gods are working so far. It’ll be so much better a festival if that is the case, encouraging people out onto the Common and to participate in things. Omnibus Theatre, our venue, has a pleasant terrace to its Bar/Cafe which overlooks the Common and that is a good place to sit in the sunshine. But the real impact will be on the walks, which would be so much more difficult in the rain. resident ) Annemarie Neary leads the second walk starting at three thirty. Our walks aren’t the same, though we do cover some of the same ground; we both start from outside Omnibus Theatre on Clapham Common Northside. Annemarie is focusing on the north and west of the Common, whereas I am doing the full circuit, though I don’t deviate from it, whereas Annemarie does.

resident ) Annemarie Neary leads the second walk starting at three thirty. Our walks aren’t the same, though we do cover some of the same ground; we both start from outside Omnibus Theatre on Clapham Common Northside. Annemarie is focusing on the north and west of the Common, whereas I am doing the full circuit, though I don’t deviate from it, whereas Annemarie does. As I write this there are some tickets still available for all of the ‘in person’ events at this year’s Clapham Book Festival, mainly because we have been moved into the bigger of the two auditoria at Omnibus Theatre. Social distancing necessarily reduces audience numbers ( one of the reasons the ticket price is higher this year ) but we should now have a good sized audience. Experience suggests that the majority of tickets are sold within the last week, with many people choosing to attend only on the day itself. So we will be selling tickets at the front desk too.

As I write this there are some tickets still available for all of the ‘in person’ events at this year’s Clapham Book Festival, mainly because we have been moved into the bigger of the two auditoria at Omnibus Theatre. Social distancing necessarily reduces audience numbers ( one of the reasons the ticket price is higher this year ) but we should now have a good sized audience. Experience suggests that the majority of tickets are sold within the last week, with many people choosing to attend only on the day itself. So we will be selling tickets at the front desk too. see him. We also have two zoom events which take place on the evenings of 19th October and 2nd November (postponed from 7th October because of illness ). I’m already preparing to interview the much praised debut novelist from Brixton, Rosanna Amaka, whose The Book of Echoes was short listed for a range of prizes, including the Royal Society of Literature’s Christopher Bland Award.

see him. We also have two zoom events which take place on the evenings of 19th October and 2nd November (postponed from 7th October because of illness ). I’m already preparing to interview the much praised debut novelist from Brixton, Rosanna Amaka, whose The Book of Echoes was short listed for a range of prizes, including the Royal Society of Literature’s Christopher Bland Award. The airport wasn’t crowded (no queues at Pret for the in-flight sandwich) though that may have had something to do with the hour – it was 5 a.m.. That’s the downside of my Ryanair flight to Jerez, the only flight available. There’s no public transport at that time in the morning either, but Pepe, my cabbie from Congo, was fun to talk to on the way. The cab from south London wasn’t cheap, but then the flight tickets were, so… My flight, on time and comfortable, was far from full.

The airport wasn’t crowded (no queues at Pret for the in-flight sandwich) though that may have had something to do with the hour – it was 5 a.m.. That’s the downside of my Ryanair flight to Jerez, the only flight available. There’s no public transport at that time in the morning either, but Pepe, my cabbie from Congo, was fun to talk to on the way. The cab from south London wasn’t cheap, but then the flight tickets were, so… My flight, on time and comfortable, was far from full.

evidence that a PCR test has been booked for one’s return. I had organised these last two before I’d left the UK and the arrangements worked well, especially the Antigen Test with Zoom, which I did when there in collaboration with a nurse who was online, somewhere else in the world. This method was considerably cheaper than any other that I’d found and entirely acceptable to the UK authorities.

evidence that a PCR test has been booked for one’s return. I had organised these last two before I’d left the UK and the arrangements worked well, especially the Antigen Test with Zoom, which I did when there in collaboration with a nurse who was online, somewhere else in the world. This method was considerably cheaper than any other that I’d found and entirely acceptable to the UK authorities.  code which successful submission generated on my phone. Rather more than a fellow traveller on the return journey had managed. He was in transit only through Stansted and hadn’t completed the Form but the Ryanair people insisted. They turned another woman away, who had failed to take a test. Her excuse was that she had planned to take one at the airport – it didn’t work, Jerez airport is very small, without any testing facilities. Other airports may offer this service, but she really should have checked.

code which successful submission generated on my phone. Rather more than a fellow traveller on the return journey had managed. He was in transit only through Stansted and hadn’t completed the Form but the Ryanair people insisted. They turned another woman away, who had failed to take a test. Her excuse was that she had planned to take one at the airport – it didn’t work, Jerez airport is very small, without any testing facilities. Other airports may offer this service, but she really should have checked. …is what I’m experiencing as I edit Opera.

…is what I’m experiencing as I edit Opera. major thoroughfares and in shops, pubs and public buildings. The carol concerts at St Martins and St Johns, the pantomimes in theatreland, the ‘Christmas show’ at the National Theatre (I have seen many over the years) and at least one, often two, productions of The Nutcracker ballet. All this contributes to the backdrop against which Opera takes place.

major thoroughfares and in shops, pubs and public buildings. The carol concerts at St Martins and St Johns, the pantomimes in theatreland, the ‘Christmas show’ at the National Theatre (I have seen many over the years) and at least one, often two, productions of The Nutcracker ballet. All this contributes to the backdrop against which Opera takes place. Each book is organised on a day by day basis. Plague runs over ten days from Monday 9th September to Wednesday 18th with a final chapter on Friday20th. Oracle begins on a Monday in November with six days in Delphi and two more, a week later, in Athens. Readers say that they like this aspect of the novels, making events seem more real and immediate as well, I am told, as pacey. Opera is no exception and a lot happens in ten days, as, I hope, readers have come to expect.

Each book is organised on a day by day basis. Plague runs over ten days from Monday 9th September to Wednesday 18th with a final chapter on Friday20th. Oracle begins on a Monday in November with six days in Delphi and two more, a week later, in Athens. Readers say that they like this aspect of the novels, making events seem more real and immediate as well, I am told, as pacey. Opera is no exception and a lot happens in ten days, as, I hope, readers have come to expect. gives our main suspects an alibi – but wait, who arrived when and who was late? The Palace of Westminster becomes relatively deserted as Members head off to their homes and constituencies and it turns into the haunt of the permanent staff and the tourists, who, while the Houses aren’t sitting, get let into the Chambers. N.B. For anyone who hasn’t visited the Palace of Westminster, the Christmas recess is a good time to go, there are generally fewer tourists than in the summer months.

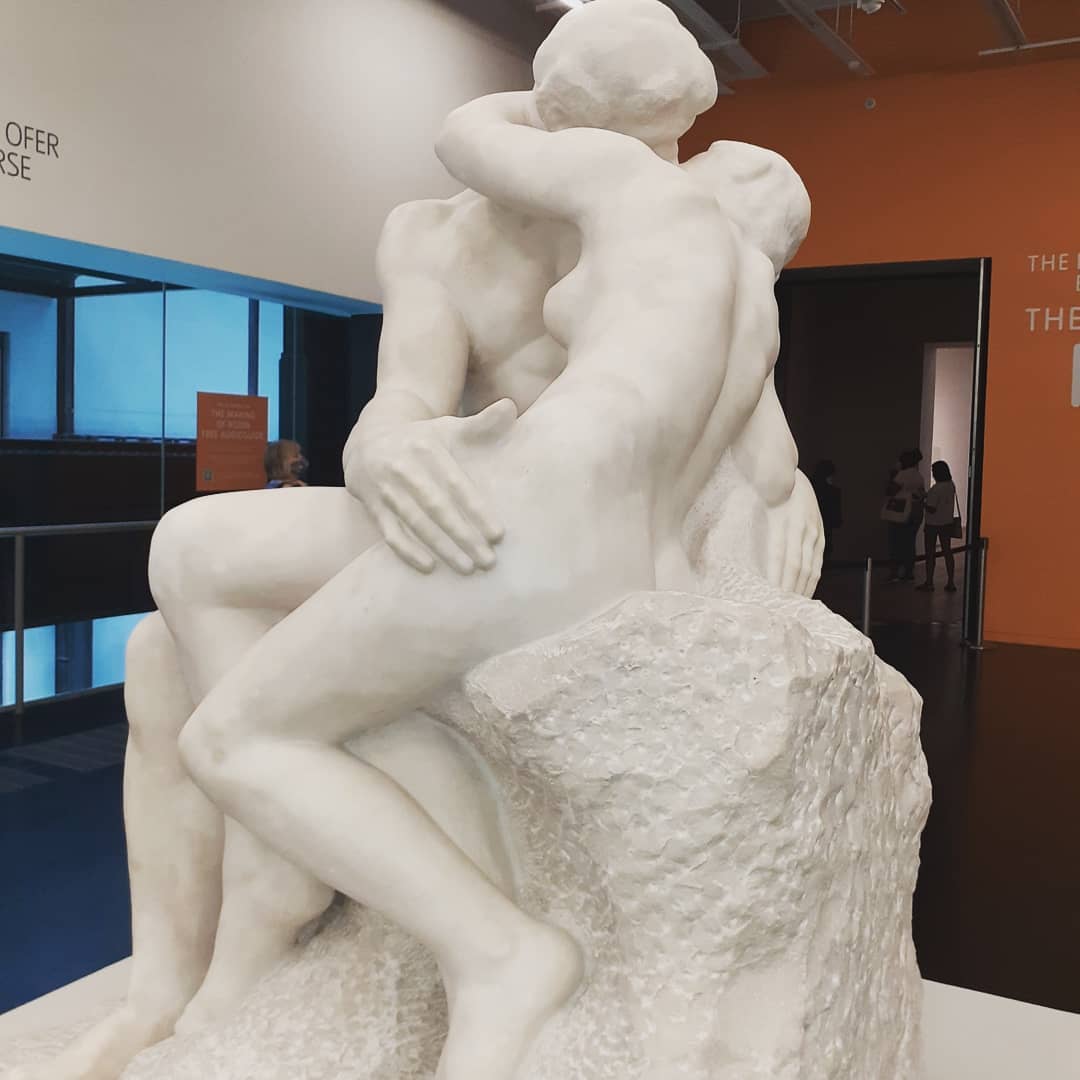

gives our main suspects an alibi – but wait, who arrived when and who was late? The Palace of Westminster becomes relatively deserted as Members head off to their homes and constituencies and it turns into the haunt of the permanent staff and the tourists, who, while the Houses aren’t sitting, get let into the Chambers. N.B. For anyone who hasn’t visited the Palace of Westminster, the Christmas recess is a good time to go, there are generally fewer tourists than in the summer months. I know nothing about sculpting, though I like looking at sculptures. So I found Tate Britain’s exhibition, The Making of Rodin, fascinating, focusing as it does on HOW Rodin went about creating his works. Outside the exhibition is a version of The Kiss, but the show itself begins with a bronze, the only bronze sculpture in the exhibition, the rest are in plaster. This is The Age of Bronze, the figure of a young Belgian soldier named Auguste Ney and it replicated real life so perfectly that Rodin was accused of making the cast direct from Ney’s body rather than modelling it. Rodin refuted the allegations of ‘cheating’ with a passion, having photographs taken of Ney to demonstrate the differences between the subject and the sculpture. Thereafter he was to move away from the conventions of classical sculpture, with its ideal of human beauty.

I know nothing about sculpting, though I like looking at sculptures. So I found Tate Britain’s exhibition, The Making of Rodin, fascinating, focusing as it does on HOW Rodin went about creating his works. Outside the exhibition is a version of The Kiss, but the show itself begins with a bronze, the only bronze sculpture in the exhibition, the rest are in plaster. This is The Age of Bronze, the figure of a young Belgian soldier named Auguste Ney and it replicated real life so perfectly that Rodin was accused of making the cast direct from Ney’s body rather than modelling it. Rodin refuted the allegations of ‘cheating’ with a passion, having photographs taken of Ney to demonstrate the differences between the subject and the sculpture. Thereafter he was to move away from the conventions of classical sculpture, with its ideal of human beauty. platre‘, which softened the sculptures, smoothing their angles and filling their craters. But a perfect finish was not what he was after and he left seams visible between joints as well as gouge and nail marks. Multiple casts of a single piece, or part of a piece were made and used in a variety of ways ( see the Giblets or abattis laid out in one vitrine, arms, legs, torsos originally to be part of The Gates of Hell, but used for many other works ). He reworked his casts, remodelling parts of them, with elements being used in any number of larger works, dismantling and reassembling existing sculptures in endless combinations. So The Head of a Slavic Woman appeared in multiple works, repositioned and rotated. The Son of Ugolino moved from prone point of death to an aerial figure.

platre‘, which softened the sculptures, smoothing their angles and filling their craters. But a perfect finish was not what he was after and he left seams visible between joints as well as gouge and nail marks. Multiple casts of a single piece, or part of a piece were made and used in a variety of ways ( see the Giblets or abattis laid out in one vitrine, arms, legs, torsos originally to be part of The Gates of Hell, but used for many other works ). He reworked his casts, remodelling parts of them, with elements being used in any number of larger works, dismantling and reassembling existing sculptures in endless combinations. So The Head of a Slavic Woman appeared in multiple works, repositioned and rotated. The Son of Ugolino moved from prone point of death to an aerial figure.  Rodin took repetition to another level when he included multiple casts of the same figure to form a sculptural group. So The Three Shades consists of a single figure, originally to represent Adam, presented in a group together (see left). He also changed the scale of pieces and the exhibition has some truly large versions of elements of other sculptures, Rodin was said to be particularly fond of the undulating surfaces created by enlargement. We see the head of one of the Burghers of Calais, but twice the size, a massive version of The Thinker and a super large plaster version of Balzac. The versions of this last sculpture are particularly illuminating, showing a nude figure in various sizes and a head in various forms, plus the dressing gown (so accurately represented it seemed that the fabric would fold in your hand), which were used to inform the final work.

Rodin took repetition to another level when he included multiple casts of the same figure to form a sculptural group. So The Three Shades consists of a single figure, originally to represent Adam, presented in a group together (see left). He also changed the scale of pieces and the exhibition has some truly large versions of elements of other sculptures, Rodin was said to be particularly fond of the undulating surfaces created by enlargement. We see the head of one of the Burghers of Calais, but twice the size, a massive version of The Thinker and a super large plaster version of Balzac. The versions of this last sculpture are particularly illuminating, showing a nude figure in various sizes and a head in various forms, plus the dressing gown (so accurately represented it seemed that the fabric would fold in your hand), which were used to inform the final work. that Rodin used drawing to study movement and the internal dynamics of the body, asking his sitters to move around the studio. The works on show are all of impersonal female nudes in graphite and watercolour and they are full of movement. I liked them a lot. As with his clay sculptures, Rodin would use the sketches again and again. The drawings on display are annotated with his notes, rotating the pages around to show the figures differently depending on aspect. The other element I admired was his use of antique artefacts – a very modern concept – though Rodin used the real thing, not copies, thus effectively negating the work of the original potter, or ceramicist (not so admirable).

that Rodin used drawing to study movement and the internal dynamics of the body, asking his sitters to move around the studio. The works on show are all of impersonal female nudes in graphite and watercolour and they are full of movement. I liked them a lot. As with his clay sculptures, Rodin would use the sketches again and again. The drawings on display are annotated with his notes, rotating the pages around to show the figures differently depending on aspect. The other element I admired was his use of antique artefacts – a very modern concept – though Rodin used the real thing, not copies, thus effectively negating the work of the original potter, or ceramicist (not so admirable). One room contains a life-size ( i.e. bigger than actual life ) plaster model of his famous Burghers of Calais, such a fabulous and powerful sculptural group, the bronze version of which stands outside the Houses of Parliament. This made me want to go and see that sculpture again, but the plain white of the plaster version somehow renders the self-sacrificing burghers even more exposed than their bronze equivalents. Other rooms are dedicated to works depicting the Japanese actor and dancer Ohta Hisa – Rodin made over fifty busts and masks of her face – and Helene von Nostitz, his aristocratic German friend.

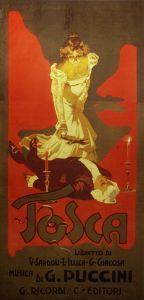

One room contains a life-size ( i.e. bigger than actual life ) plaster model of his famous Burghers of Calais, such a fabulous and powerful sculptural group, the bronze version of which stands outside the Houses of Parliament. This made me want to go and see that sculpture again, but the plain white of the plaster version somehow renders the self-sacrificing burghers even more exposed than their bronze equivalents. Other rooms are dedicated to works depicting the Japanese actor and dancer Ohta Hisa – Rodin made over fifty busts and masks of her face – and Helene von Nostitz, his aristocratic German friend.  Is it entirely coincidental that, at a time when I’m working on ‘Opera’, the next novel in the Cassandra Fortune series, I’m going to more opera than usual? No, of course not. The opera in ‘Opera’ is Tosca, Puccini’s ‘shabby little shocker’ (according to musicologist Joseph Kerman) set in Rome on 17th and 18th June 1800. The dating is precise because the plot is impacted by specific events, in particular the outcome, for some time in doubt, of the Battle of Marengo then taking place far to the north. The date of events in ‘Opera’ is precise too, though opera and novel have more in common than that. Both have a political backdrop of democracy under siege by the forces of repression and wealth, both have an arch-villain and a courageous heroine. I’m off to see ENO present this later in the summer.

Is it entirely coincidental that, at a time when I’m working on ‘Opera’, the next novel in the Cassandra Fortune series, I’m going to more opera than usual? No, of course not. The opera in ‘Opera’ is Tosca, Puccini’s ‘shabby little shocker’ (according to musicologist Joseph Kerman) set in Rome on 17th and 18th June 1800. The dating is precise because the plot is impacted by specific events, in particular the outcome, for some time in doubt, of the Battle of Marengo then taking place far to the north. The date of events in ‘Opera’ is precise too, though opera and novel have more in common than that. Both have a political backdrop of democracy under siege by the forces of repression and wealth, both have an arch-villain and a courageous heroine. I’m off to see ENO present this later in the summer. nobleman who is condemned to Hell for impersonating a dead man in order to acquire his property (including an ass). The company, St Paul’s Opera, is based at a Clapham church. It was set up by Patrician Ninian and others (who have since moved on) with the specific aim of offering accessible opera while encouraging and supporting aspiring young professional singers. Some of the finest were singing last week. It was, as it always is, a sell-out.

nobleman who is condemned to Hell for impersonating a dead man in order to acquire his property (including an ass). The company, St Paul’s Opera, is based at a Clapham church. It was set up by Patrician Ninian and others (who have since moved on) with the specific aim of offering accessible opera while encouraging and supporting aspiring young professional singers. Some of the finest were singing last week. It was, as it always is, a sell-out. company who were to appear later in the opera.

company who were to appear later in the opera. and walked down to the amphitheatre. What a joy it was to be part of a happy crowd of people again, all anticipating more fun to come.

and walked down to the amphitheatre. What a joy it was to be part of a happy crowd of people again, all anticipating more fun to come. Clapham’s quirky and much-loved literary festival is back for 2021, taking place on 16 October. It will feature events in a variety of formats, including literary walks and livestreaming of events as well as the usual live author discussions. This year will also see a number of online literary events during the summer and autumn in the lead up to the event in October, which will be delivered in partnership with Time & Leisure Magazine.

Clapham’s quirky and much-loved literary festival is back for 2021, taking place on 16 October. It will feature events in a variety of formats, including literary walks and livestreaming of events as well as the usual live author discussions. This year will also see a number of online literary events during the summer and autumn in the lead up to the event in October, which will be delivered in partnership with Time & Leisure Magazine. around the literary sites of Clapham led by local authors, including the novelist and award-winning short story writer Annemarie Neary and crime fiction writer, Julie Anderson. Clapham has a long and illustrious literary history and this is a unique way of exploring it, but ticket numbers are limited so be sure to get yours early. Although we cannot be sure what level of restrictions will apply in October, if any, the walks will take place regardless of all but the strictest of lock-down circumstances.”

around the literary sites of Clapham led by local authors, including the novelist and award-winning short story writer Annemarie Neary and crime fiction writer, Julie Anderson. Clapham has a long and illustrious literary history and this is a unique way of exploring it, but ticket numbers are limited so be sure to get yours early. Although we cannot be sure what level of restrictions will apply in October, if any, the walks will take place regardless of all but the strictest of lock-down circumstances.” newspaper, will be discussing his most recent book Agent Sonya, a biography of Soviet agent, Ursula Kuszinsky and trading stories of legendary spies with local author and broadcaster Simon Berthon.

newspaper, will be discussing his most recent book Agent Sonya, a biography of Soviet agent, Ursula Kuszinsky and trading stories of legendary spies with local author and broadcaster Simon Berthon. & Leisure Magazine. This is a new departure for the Festival. It will bring high quality author interviews, often with local authors or writers connected with Clapham and south London to a wider audience all year round. Panel discussions and conversations are planned. The first of these, with best-selling local author Elizabeth Buchan, whose new book Two Women of Rome was published in June, will be taking place on 28 July. Elizabeth will be discussing her work, the settings for her books and the importance of history in her books. This is a free event to inaugurate the programme but please register at Eventbrite

& Leisure Magazine. This is a new departure for the Festival. It will bring high quality author interviews, often with local authors or writers connected with Clapham and south London to a wider audience all year round. Panel discussions and conversations are planned. The first of these, with best-selling local author Elizabeth Buchan, whose new book Two Women of Rome was published in June, will be taking place on 28 July. Elizabeth will be discussing her work, the settings for her books and the importance of history in her books. This is a free event to inaugurate the programme but please register at Eventbrite  , 2004), the latter opera performed around the world. She is currently working on a piece to be performed in her native Australia. Philip Hensher is better known as a novelist, twice listed for the Man Booker Prize (The Mulberry Empire, 2002 and The Northern Clemency, 2008) but has an abiding love of opera and produced the libretto to Thomas Ades’ debut opera Powder Her Face (1995). His latest book is A Small Revolution in Germany (Fourth Estate, 2020). The discussion was marshalled by Jonathan Boardman, Vicar of St Pauls, Clapham, where the event took place.

, 2004), the latter opera performed around the world. She is currently working on a piece to be performed in her native Australia. Philip Hensher is better known as a novelist, twice listed for the Man Booker Prize (The Mulberry Empire, 2002 and The Northern Clemency, 2008) but has an abiding love of opera and produced the libretto to Thomas Ades’ debut opera Powder Her Face (1995). His latest book is A Small Revolution in Germany (Fourth Estate, 2020). The discussion was marshalled by Jonathan Boardman, Vicar of St Pauls, Clapham, where the event took place. by chance, it was he who suggested the subject of Ades’ first opera, the scandalous divorce between the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, which became Powder Her Face. He described the process as a suggestive and seductive one, the librettist leaving a trail of breadcrumbs (words) to entice the composer into following creatively and then to exceed the limitations of those words. Oakes described the process differently, more of a collaboration in joy. She took on the task of writing the libretto for an opera based on Shakespeare which was filled with particular challenges. She described the process as being like ‘walking around a monument, seeing it from different angles and bringing out its different aspects’. Should she adopt iambic pentameter, the verse form used most frequently by Shakespeare? Yet it might constrain or run directly against the meter of the music. Should she use it occasionally, or abandon it altogether? She also had a particular problem in that, in the play the heroine Miranda, daughter of Prospero, says very little. Oakes had to get inside the head of this character and give her more of a voice, bringing out her hopes and fears in order for her to act as a balance within the opera.

by chance, it was he who suggested the subject of Ades’ first opera, the scandalous divorce between the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, which became Powder Her Face. He described the process as a suggestive and seductive one, the librettist leaving a trail of breadcrumbs (words) to entice the composer into following creatively and then to exceed the limitations of those words. Oakes described the process differently, more of a collaboration in joy. She took on the task of writing the libretto for an opera based on Shakespeare which was filled with particular challenges. She described the process as being like ‘walking around a monument, seeing it from different angles and bringing out its different aspects’. Should she adopt iambic pentameter, the verse form used most frequently by Shakespeare? Yet it might constrain or run directly against the meter of the music. Should she use it occasionally, or abandon it altogether? She also had a particular problem in that, in the play the heroine Miranda, daughter of Prospero, says very little. Oakes had to get inside the head of this character and give her more of a voice, bringing out her hopes and fears in order for her to act as a balance within the opera. librettists speaking last night remain friends with the composers they had worked with, but there are some examples of the relationship between collaborators breaking down. So much so in Harrison Birtwhistle’s case that one of his librettists alleged that Birtwhistle had tried to run him down with his car! Gilbert and Sullivan cordially hated each other (though they made a lot of money together). On the other hand there have been some great collaborations between partners, like that between Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears (though Britten was, apparently, notoriously difficult to work with).

librettists speaking last night remain friends with the composers they had worked with, but there are some examples of the relationship between collaborators breaking down. So much so in Harrison Birtwhistle’s case that one of his librettists alleged that Birtwhistle had tried to run him down with his car! Gilbert and Sullivan cordially hated each other (though they made a lot of money together). On the other hand there have been some great collaborations between partners, like that between Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears (though Britten was, apparently, notoriously difficult to work with). ages, by Purcell, Handel, Gilbert & Sullivan and Britten. The young singers, Hugh Benson (tenor), Alexandra Dinwiddie (mezzo-soprano), Edwin Kaye (bass cantate) and Davidona Pittock (soprano) were from St Paul’s Opera, accompanied by pianist Elspeth Wilkes.

ages, by Purcell, Handel, Gilbert & Sullivan and Britten. The young singers, Hugh Benson (tenor), Alexandra Dinwiddie (mezzo-soprano), Edwin Kaye (bass cantate) and Davidona Pittock (soprano) were from St Paul’s Opera, accompanied by pianist Elspeth Wilkes.