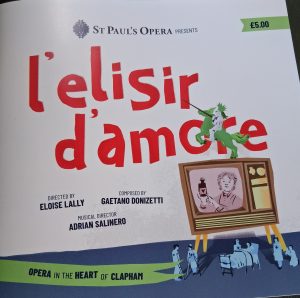

Earlier this year I was approached by Patricia Ninian of St Paul’s Opera company with the suggestion that I should work with them on their summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore by Donizetti. The director, Eloise Lally (English Touring Opera) wanted to set the production in a hospital after the second world war. Patricia had read my book, The Midnight Man and spotted the synergies immediately, especially as ‘my’ hospital was based on a real, Clapham hospital – the South London Hospital for Women and Children. I was invited to rehearsals and I began to keep a rehearsal diary, a version of which follows.

Earlier this year I was approached by Patricia Ninian of St Paul’s Opera company with the suggestion that I should work with them on their summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore by Donizetti. The director, Eloise Lally (English Touring Opera) wanted to set the production in a hospital after the second world war. Patricia had read my book, The Midnight Man and spotted the synergies immediately, especially as ‘my’ hospital was based on a real, Clapham hospital – the South London Hospital for Women and Children. I was invited to rehearsals and I began to keep a rehearsal diary, a version of which follows.

Saturday 17th May

It’s the first full day of rehearsals and Eloise Lally, the Director, sits in a front pew blocking out stage positions and movement for the chorus. Most members of the chorus are here, taking up their places and moving at the direction of Eloise. Outside the sky is blue. Sunshine makes angular shadows on the deep window embrasures.

It’s obvious that there’s been previous discussions about the setting – in the South London Hospital, Clapham during the period following the end of World War two – and its fruits are evident.

‘Is this where the bed will be?’ asks a chorus member.

‘You’re sitting on it,’ responds Eloise.

The stage is bare.

Yet there is also a television, a relative rarity in late 1940s London, but certainly possible in a hospital common room. Chorus members stare at the invisible item, transfixed by its novelty.

Individual chorus members already have characters. So, I meet Pam, a south London girl, with the accent on ‘sarf’. A middle-aged lady with lumbago, she is never seen without a cigarette in her fingers. Many chorus members are halt and lame, patients of the hospital and walking wounded. These ‘characters’ give both variation and verisimilitude to what would otherwise simply be an amorphous group.

on ‘sarf’. A middle-aged lady with lumbago, she is never seen without a cigarette in her fingers. Many chorus members are halt and lame, patients of the hospital and walking wounded. These ‘characters’ give both variation and verisimilitude to what would otherwise simply be an amorphous group.

Eloise doesn’t only place the chorus physically, but also psychologically. She tells us that all the chorus characters know that Nemorino is hopelessly in love with Adina, who is so far out of his reach. Most of them feel sorry for him. They see, at the beginning of Act 2, that the lovelorn suitor buys something from Dr Dulcamara and are curious about what. Hospitals are places where gossip and rumour often run unchecked and L’Elisir’s South London is no different.

Throughout the pianist plays and replays accompaniment and also sings the soloists parts where necessary sometimes to the amusement of the cast. She is aided in the tenor role by Edvard Adde (the Norwegian tenor, cover for the role of Nemorino).

Throughout the pianist plays and replays accompaniment and also sings the soloists parts where necessary sometimes to the amusement of the cast. She is aided in the tenor role by Edvard Adde (the Norwegian tenor, cover for the role of Nemorino).

At two o’clock we break for lunch and many of the singers head towards Clapham Common and the crowds who are enjoying the weekend sunshine, while others remain closer by in the dappled shade of the peaceful churchyard. Back to resume at three!

Saturday 24th May

It is one week and several rehearsals on and there are more singers in a rather chilly church. This time the chorus and three of the principals are here, as is the Director of Music, Adrian Salinero at the piano, as well as Eloise. Outside the sky is grey.

We go ‘from the top’ Act I, Scene I and singers enter from different parts of the church to take their places on stage. Chorus members ‘characters’ do their stage business and eventually settle down to watch the new-fangled television. Matron Adina (Dorset-born soprano, Fiona Hymns) consults with Nurse Gianetta (Isabella Roberts), then it’s straight into her first aria.

new-fangled television. Matron Adina (Dorset-born soprano, Fiona Hymns) consults with Nurse Gianetta (Isabella Roberts), then it’s straight into her first aria.

The interplay between principals and with other cast members is taking shape. Belcore (baritone, Theodore ‘Ted’ Day) is a delusional patient who imagines he is still fighting the war, he treats everyone as if they’re in his military company and the rest of the cast plays along with tolerant affection. He preens himself in preparation for his declaration of love for Adina. Her exasperated astonishment, when he makes it, is very funny, without being in any way cruel. I laughed aloud.

Dr Dulcamara (Essex-born baritone Ashley Mercer) makes a dramatic entrance and begins his spiel, producing all manner of ‘wonders’ from his capacious bag and offering, at a one-time-only knock-down price, his miracle wonder cure for all ailments.

The chorus is impressed. Matron Adina is not. The rehearsal ends with their mini-confrontation.

Eloise calls the singers together and gives them notes, about movement, stage business and psychology. The chorus are to remain still and rapt as Matron Adina sings her aria. She is most definitely in charge, but she is also their healer, so they are both overawed and grateful. Belcore is too static, holding his rose for Adina and should make more of his preparation. The relationship between Adina and Dulcamara needs more definition.

Eloise calls the singers together and gives them notes, about movement, stage business and psychology. The chorus are to remain still and rapt as Matron Adina sings her aria. She is most definitely in charge, but she is also their healer, so they are both overawed and grateful. Belcore is too static, holding his rose for Adina and should make more of his preparation. The relationship between Adina and Dulcamara needs more definition.

Through-out Adrian insists that the singers keep tempo and, occasionally, gives notes of his own, mainly to the chorus.

In the lunch break I meet a few more of the chorus members’ characters; there’s Charles, a professional military man wounded in the war, hitching up his trousers when he sits – ramrod straight despite his damaged leg – to avoid stretching their fabric. Luigi, an Italian wounded in the Great War fighting Britain, who came to Clapham following the Londoner nurse who tended him and who is now a stalwart member of the community. He sells newspapers just outside the hospital.

Then it’s back to the South London Hospital to take it ‘from the top’ again.

Tuesday 10th June

It’s an evening rehearsal at St Paul’s and low sun shines in through windows on the opposite side of the church. Eloise makes tea and Adrian is at the piano, as two soloists, Latvian tenor Martins Smaukstelis (Nemorino) and Ashley Mercer (Dr Dulcamara) arrive. They will concentrate on their duet scene in Act One, in which the crafty doctor sells the naïve Nemorino his ‘elixir of love’.

There is a sing through first and male voices echo around the church. Then a quick discussion with Adrian.

There is a sing through first and male voices echo around the church. Then a quick discussion with Adrian.

‘Shall we?’ says Eloise.

The soloists take up positions.

Nemorino approaches Dulcamara with a mixture of desperate hope, excitement and fear. Can this ‘alchemist’ help him win Adina? Dulcamara cannot believe his luck and quickly rips a label from a bottle of red wine, offering it as the famed elixir for all the money in Nemorino’s pockets. The doctor rolls his eyes at the audience, who are complicit in his ruse. Then he wants to get away before his victim twigs, but Nemorino calls him back. How does he use the elixir?

There follows a very funny scene in which the doctor instructs Nemorino in how to open a bottle of wine. This scene is, as Eloise says, ‘all about the bench’, where the two characters sit and most of their interaction happens.

As I watch another kind of alchemy takes place.

Eloise offers suggestions but allows her soloists room to create. These two are almost affectionate, she suggests, they like each other. The doctor invites Nemorino to sit, his gestures and instructions become fatherly in tone. Nemorino is trusting, child-like. The action emerges, through physical gesture as much as song, the singers acting and interacting spontaneously.

Nemorino’s tigerish enthusiasm bubbles over and he starts to rush away, to share his good fortune. Dulcamara realises that if other learn of this, the game will be up, his trickery exposed, so he calls Nemorino back to persuade him to keep the elixir secret. The scene ends in more subdued fashion, as Nemorino is, as Eloise says ‘looking inward’. The tone changes.

We run through again, this time in full voice. Stage action now fits seamlessly to the music – when Nemorino plucks up courage to approach Dulcamara there is what Eloise describes as ‘walking music’ and that’s exactly what it sounds like. The handshake between the two men comes at the climax of a passage of music, carrying over to signal in sound what Dulcamara signals physically – that he cannot extricate his hand from Nemorino’s grateful grasp.

Doubtless there will be refinement, but a scene, musically and emotionally consistent, dramatic and very funny, has come into being where none existed before.

This is alchemy indeed.

Tuesday 17th June

The church is bathed in soft evening light and the whole of the cast is here. So is David Butt Phillip, international opera star and patron of St Paul’s Opera, so the church pews are dotted with a select audience, the VIP Friends of SPO. This is the first time David has seen this developing production. Adrian is at the piano and Eloise is in her customary place.

audience, the VIP Friends of SPO. This is the first time David has seen this developing production. Adrian is at the piano and Eloise is in her customary place.

The singers, especially the soloists, are on their mettle in David’s presence and one or two show signs of nervousness. Plus, Eloise will be focusing more on the soloists this evening, she explains, so as to reinforce the emotional story-telling throughout.

We go from Adina’s first aria in Act One. David reminds the chorus that their staccato phrases towards the end of Adina’s aria should be crisp and succinct beneath the rich and soaring soprano voice, ‘half as long and half as loud’. We repeat and transition into Belcore’s ‘proposal’ aria. There is business here for Nemorino, overhearing Belcore’s declaration of love and reacting to the proposal to his beloved Adina. As Eloise and Martins consider some repositioning, David advises Ted on his stance which should be ‘less  elegant, more military, butch, showing Belcore believes that he’s ready for anything’.

elegant, more military, butch, showing Belcore believes that he’s ready for anything’.

We go again. This time Belcore’s marshalling of his ‘troop’ is more militarily done and obviously for Adina’s benefit. The chorus exits in single file, marching. David advises that, without a conductor to cue them, they have to take responsibility for getting on top of the music, thinking about what’s to come several bars in advance and attacking it ‘on point’. Otherwise the sound will be ‘mushy’.

The first duet between the romantic leads follows, but this isn’t a standard lovers’ duet, it is more complex. Eloise wants clarity of emotional story-telling and so, in the break, she discusses the duet, almost line by line with the two singers, asking each, like a therapist, to describe the feelings of their characters at that point in the aria. So, when we begin again we have flirting, devotion, apparent rejection and pleasure in each other.

And on to Dr Dulcamara’s entrance…

30th June 2025

It is the hottest day of the year so far and the interior of the church feels mercifully cool after the hard sun outside. There are quite a few folk around – a professional photographer, the light and sound technicians, various people unknown to me (donors, critics?) as well as the cast and the musicians.

It is the hottest day of the year so far and the interior of the church feels mercifully cool after the hard sun outside. There are quite a few folk around – a professional photographer, the light and sound technicians, various people unknown to me (donors, critics?) as well as the cast and the musicians.

The stage is, literally, set. It is multi-level in three main blocks and with lots of entrances and exits, perfect for lots of motion in a comedic piece. The red brick walls of the South London Hospital are to the fore, there is a hospital bed, screens, trolley and other ward paraphernalia. On the stage is an old-fashioned, wooden box TV with doors; to either side of the stage are flatscreens to carry surtitles. Strings of lights are hung across the church, they will be illuminated later as darkness falls.

Nurses in 1940/50s uniforms mingle with patients in pyjamas or nightdresses. Ashley (Dr Dulcamara) and Fiona (Adina) wait until the last minute to don their costumes, which are heavy in the heat – especially Dulcamara’s tight fitting leather aviator hat. Musicians arrive one by one and Adrian sits them in their places and begins to talk about the music, while using a bright fan as if to the manner born (he hails from the Basque country, so he probably was). The church begins to feel hotter.

Eloise is everywhere; she’s up in the balcony, checking the sightlines, on stage with Ted (Belcore) discussing how he will enlist Nemorino (by using his own medical chart) and with the cast in the Green Room.

Eloise is everywhere; she’s up in the balcony, checking the sightlines, on stage with Ted (Belcore) discussing how he will enlist Nemorino (by using his own medical chart) and with the cast in the Green Room.

The musicians are all here, so… we begin!

I have heard much of this many times before, but it seems fresh and different now. This is the added element which costumes and staging bring. They also add physical authority to the concept of setting the opera in a post-war Clapham hospital. I knew it would work, but now it seems inspired.

The Adina-Nemorino dynamic is immediate and very strong, as befits the central relationship of the story. The nurses chat and inter-react like workmates. The south Londoners add variety and colour (as well as sound). Music and voices reverberate around the church (it will be interesting to see what sort of impact a full audience will have on the sound).

The spirit of the piece is celebratory and there is a slight carnival aspect, even though it is set in a hospital. It is funny and moving and beautiful. I feel so privileged to have watched this production develop, to talk with the director and soloists and chorus members at various stages. Thank you, all of you.

L’Elisir d’Amore is going to be an enormous success.

N.B. Since this diary was written the St Paul’s Opera Summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore has been given an Assessors Award from the Offie’s which celebrate independent and fringe theatre. Watch this space for a Nomination!

This year saw a unique collaboration for me, with St Paul’s Opera Company, on their production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore (The Elixir of Love). The Director, Eloise Lally, wanted to set her version of the opera in a hospital immediately post-World War two and Patricia Ninian, SPO founder and Director had read my books The Midnight Man and A Death in the Afternoon, which are set in the South London Hospital for Women and Children. So Tricia approached me to see if using that setting might work. I was sure it would.

This year saw a unique collaboration for me, with St Paul’s Opera Company, on their production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore (The Elixir of Love). The Director, Eloise Lally, wanted to set her version of the opera in a hospital immediately post-World War two and Patricia Ninian, SPO founder and Director had read my books The Midnight Man and A Death in the Afternoon, which are set in the South London Hospital for Women and Children. So Tricia approached me to see if using that setting might work. I was sure it would. in time when men were returning home from the war to take up the jobs and roles they had left behind, which had, in their absence, been done by women. Not all the women, especially the younger ones, wanted to return to a purely domestic sphere, but they had little choice. At the South London, however, the opposite was happening. Male medics and staff were leaving, to be replaced by women and male patients were also being excluded. This unique point of tension informed my books and would inform the opera.

in time when men were returning home from the war to take up the jobs and roles they had left behind, which had, in their absence, been done by women. Not all the women, especially the younger ones, wanted to return to a purely domestic sphere, but they had little choice. At the South London, however, the opposite was happening. Male medics and staff were leaving, to be replaced by women and male patients were also being excluded. This unique point of tension informed my books and would inform the opera. small exhibition about the South London, using documents and memorabilia lent to us by Dr Juliet Boyd, former anaesthetist at the hospital and its unofficial archivist. This included everything from an annual report from 1917, showing the medical officers in post (all female – the only male name is that of a chaplain) to protest badges against the closure of the hospital almost seventy years later. The banners (right, with SPO Director, Patricia Ninian) produced by the opera company would be used as information at each of the performances.

small exhibition about the South London, using documents and memorabilia lent to us by Dr Juliet Boyd, former anaesthetist at the hospital and its unofficial archivist. This included everything from an annual report from 1917, showing the medical officers in post (all female – the only male name is that of a chaplain) to protest badges against the closure of the hospital almost seventy years later. The banners (right, with SPO Director, Patricia Ninian) produced by the opera company would be used as information at each of the performances.

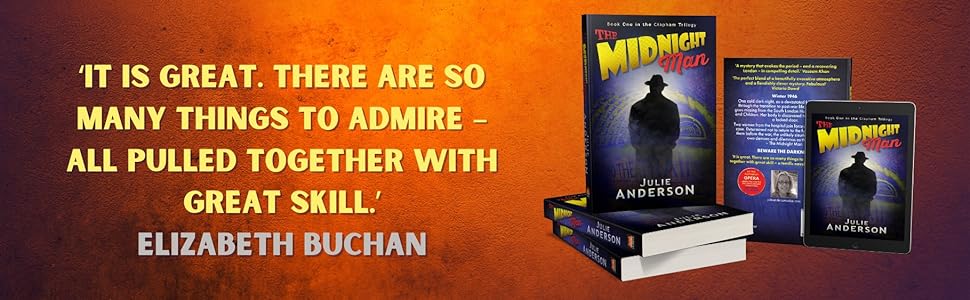

Only three weeks to go before my next book is published (by Hobeck Books) and I’ve received some very complimentary comments from fellow authors who have read proofs, like Vaseem Khan (award-winning author of the Malabar House series, set in 1950s India), Victoria Dowd (award-winning author of the Smart Woman series) and Elizabeth Buchan (multi-award winner and fellow south Londoner ). This is the enjoyable time, the pleasant anticipation, the dream of a best-seller, unsullied by one star reviews or poor sales numbers.

Only three weeks to go before my next book is published (by Hobeck Books) and I’ve received some very complimentary comments from fellow authors who have read proofs, like Vaseem Khan (award-winning author of the Malabar House series, set in 1950s India), Victoria Dowd (award-winning author of the Smart Woman series) and Elizabeth Buchan (multi-award winner and fellow south Londoner ). This is the enjoyable time, the pleasant anticipation, the dream of a best-seller, unsullied by one star reviews or poor sales numbers. so I’ll be speaking at the Clapham Society and local libraries and book clubs. Some are London wide – the London Transport Museum is carrying the book in its shop and I’ll be working with them to be part of their events calendar. Some are national – so I’ll be part of the Royal College of Nursing’s Summer exhibition and events programme, which is taking place across the country. I’m looking forward to attending its launch on 10th May (see above).

so I’ll be speaking at the Clapham Society and local libraries and book clubs. Some are London wide – the London Transport Museum is carrying the book in its shop and I’ll be working with them to be part of their events calendar. Some are national – so I’ll be part of the Royal College of Nursing’s Summer exhibition and events programme, which is taking place across the country. I’m looking forward to attending its launch on 10th May (see above). not a medic, though she worked for the RCN; a third generation involvement with nursing and medicine, albeit in a different capacity to her surgeon great grandmother. She told me lots of stories about Maud, known by the family as ‘Aunt Mary’ and sent me a photograph of her portrait, which currently hangs in Antonia’s mother’s house in London.

not a medic, though she worked for the RCN; a third generation involvement with nursing and medicine, albeit in a different capacity to her surgeon great grandmother. She told me lots of stories about Maud, known by the family as ‘Aunt Mary’ and sent me a photograph of her portrait, which currently hangs in Antonia’s mother’s house in London. I don’t know the answer to that and neither did Antonia. I hope to be able to speak with her father, who has a fund of stories about ‘Aunt Mary’ which might be enlightening. Nonetheless, I like to think that Maud, who had probably developed something of a thick skin by this time – she was denounced from the pulpit by her minister father (he said he would rather she died than became a doctor) when she was younger and had to blaze trails in other ways, decided, rather like Groucho Marx, not to join any club which would have her as a member, especially one which, in years previously, would not admit her.

I don’t know the answer to that and neither did Antonia. I hope to be able to speak with her father, who has a fund of stories about ‘Aunt Mary’ which might be enlightening. Nonetheless, I like to think that Maud, who had probably developed something of a thick skin by this time – she was denounced from the pulpit by her minister father (he said he would rather she died than became a doctor) when she was younger and had to blaze trails in other ways, decided, rather like Groucho Marx, not to join any club which would have her as a member, especially one which, in years previously, would not admit her. This is not the only remarkable coincidence attaching to this book. Early in the writing process, at first draft stage, I received an unanticipated invitation to a birthday celebration for a friend and couldn’t (for reasons too tedious to go into here) buy a birthday gift in time. So my gift was to name a character after my friend in the new book. I duly did so and, just prior to final editing, I sent her a copy of the manuscript. If she hadn’t liked ‘her’ character, or had had second thoughts about my using her name, she could withdraw and I would change the name. She and her partner, who also had a named character, were very happy, though she responded by sending me a copy of the birth certificate of her first born son. He was born at the South London Hospital in the 1970s! She had never mentioned where he was born (he now lives in Canada) so I had no idea. Thus, I found, my friend was a real patient at the real hospital as well as being a ‘character’ in the fictional version. What are the chances of that?

This is not the only remarkable coincidence attaching to this book. Early in the writing process, at first draft stage, I received an unanticipated invitation to a birthday celebration for a friend and couldn’t (for reasons too tedious to go into here) buy a birthday gift in time. So my gift was to name a character after my friend in the new book. I duly did so and, just prior to final editing, I sent her a copy of the manuscript. If she hadn’t liked ‘her’ character, or had had second thoughts about my using her name, she could withdraw and I would change the name. She and her partner, who also had a named character, were very happy, though she responded by sending me a copy of the birth certificate of her first born son. He was born at the South London Hospital in the 1970s! She had never mentioned where he was born (he now lives in Canada) so I had no idea. Thus, I found, my friend was a real patient at the real hospital as well as being a ‘character’ in the fictional version. What are the chances of that? Two happy accidents; I hope they bode well for the book. ‘The Midnight Man’ is published by Hobeck Books on 30th April. I will be posting further pieces about it as the date approaches. Available for pre-order from Mr Besos’

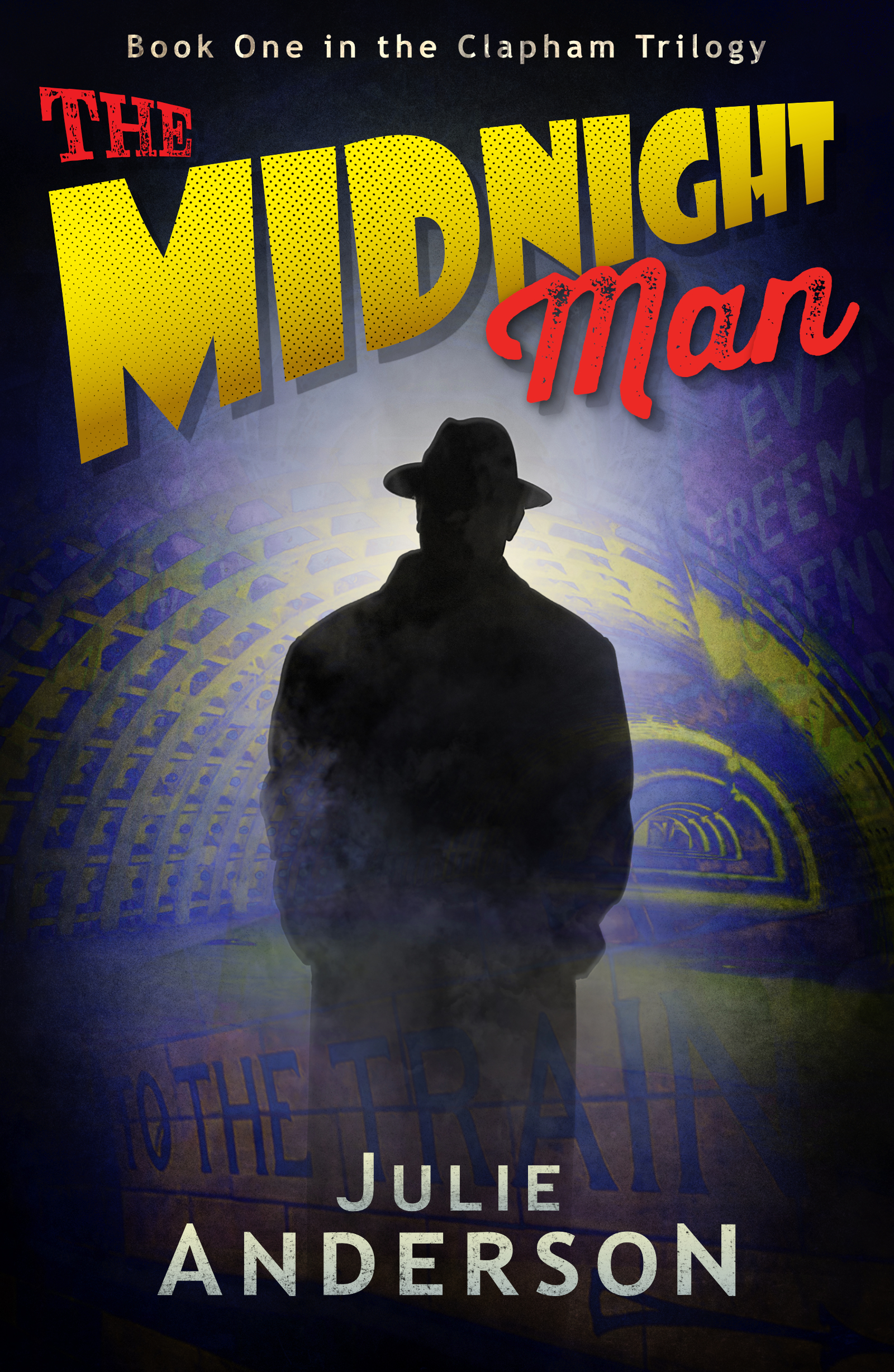

Two happy accidents; I hope they bode well for the book. ‘The Midnight Man’ is published by Hobeck Books on 30th April. I will be posting further pieces about it as the date approaches. Available for pre-order from Mr Besos’  I am very pleased with the cover of my next novel, The Midnight Man. Created by graphic designer,

I am very pleased with the cover of my next novel, The Midnight Man. Created by graphic designer,

hereby hangs another tale, which I will doubtless return to.

hereby hangs another tale, which I will doubtless return to. Clapham Common, clustered around Clapham South Underground station. Some of these places are highly unusual, some still exist (although they have been repurposed) and others can be visited today.

Clapham Common, clustered around Clapham South Underground station. Some of these places are highly unusual, some still exist (although they have been repurposed) and others can be visited today. large donation which, some speculated, came from a female member of the royal family, they collected enough to found the South London Hospital for Women and Children. At first the hospital operated in two large houses near Clapham South tube station, but, in 1916, Queen Mary opened a purpose-built eighty bed hospital, the largest women’s general hospital in the UK.

large donation which, some speculated, came from a female member of the royal family, they collected enough to found the South London Hospital for Women and Children. At first the hospital operated in two large houses near Clapham South tube station, but, in 1916, Queen Mary opened a purpose-built eighty bed hospital, the largest women’s general hospital in the UK. fondly remembered the ‘South London’ or ‘SLH’. There is even a Facebook group, to which I now belong, entitled South London Women’s Hospital occupation 1984─85 where those who protested at the time, many of them staff and patients, reminisce and organize the occasional get together. So, there was a certain amount of pressure to get it right.

fondly remembered the ‘South London’ or ‘SLH’. There is even a Facebook group, to which I now belong, entitled South London Women’s Hospital occupation 1984─85 where those who protested at the time, many of them staff and patients, reminisce and organize the occasional get together. So, there was a certain amount of pressure to get it right. unusual one ( I’ll be blogging about it as publication day approaches ). Some of its buildings still stand, near Clapham South Underground station as the photograph (right) shows. This was the ‘New Wing’ erected in the 1930s. It is now an apartment building, above a supermarket ( the entrance to which can just be seen on the far left).

unusual one ( I’ll be blogging about it as publication day approaches ). Some of its buildings still stand, near Clapham South Underground station as the photograph (right) shows. This was the ‘New Wing’ erected in the 1930s. It is now an apartment building, above a supermarket ( the entrance to which can just be seen on the far left). connected with it.

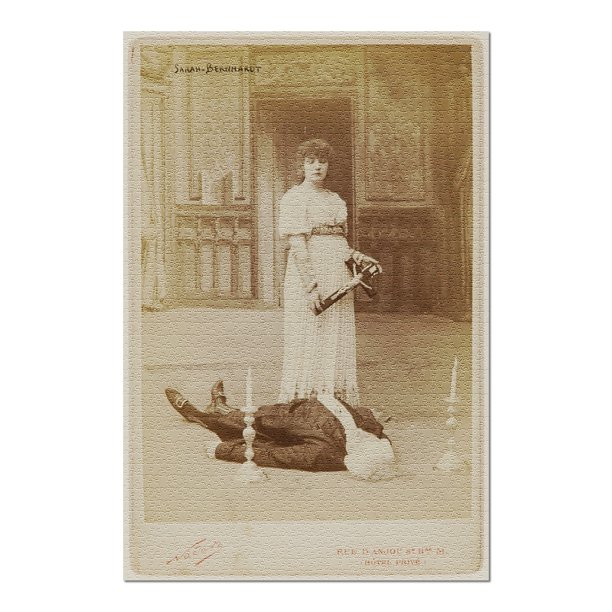

connected with it. Puccini’s opera was based. The first performance of the opera was in 1900 in Rome and the poster was by Adolfo Hohenstein who also designed the stage sets. It is very much in the Art Noveau style of Mucha and features the same scene as the Bernhardt postcard, a scene which was to feature again and again in images of the opera. The pious Tosca sets candles at the head of the Baron, whom she has just killed ( in self-defence, as he has just tried to rape her ) and places a crucifix on his chest.

Puccini’s opera was based. The first performance of the opera was in 1900 in Rome and the poster was by Adolfo Hohenstein who also designed the stage sets. It is very much in the Art Noveau style of Mucha and features the same scene as the Bernhardt postcard, a scene which was to feature again and again in images of the opera. The pious Tosca sets candles at the head of the Baron, whom she has just killed ( in self-defence, as he has just tried to rape her ) and places a crucifix on his chest. Many of the more modern images are explicit about the subject matter and the link the opera makes between sex and death (see left). The dagger is a recurring motif, as is blood – red is the most popular colour. The Castel Sant’Angelo appears too. Tosca herself, as in Bernhardt’s time, is often the the central image, although other posters prefer to concentrate on Scarpia, like that for Florida State Opera (right). Only a few depict Cavaradossi, the hero. Ordinarily one might say that this is an example of

Many of the more modern images are explicit about the subject matter and the link the opera makes between sex and death (see left). The dagger is a recurring motif, as is blood – red is the most popular colour. The Castel Sant’Angelo appears too. Tosca herself, as in Bernhardt’s time, is often the the central image, although other posters prefer to concentrate on Scarpia, like that for Florida State Opera (right). Only a few depict Cavaradossi, the hero. Ordinarily one might say that this is an example of  ‘the devil has all the best tunes’, except that in the opera itself, it is the tenor arias, belonging to Cavaradossi, which are most memorable.

‘the devil has all the best tunes’, except that in the opera itself, it is the tenor arias, belonging to Cavaradossi, which are most memorable. A metal box, that’s all it is. Not precious metal either, probably brass, at least that’s how it looks when polished, though bits are silver in colour, so it could possibly be tin or another alloy. Approximately 130 centimetres across, 85 from front edge to back and 30cm/1 inch deep, it would fit in a uniform pocket.

A metal box, that’s all it is. Not precious metal either, probably brass, at least that’s how it looks when polished, though bits are silver in colour, so it could possibly be tin or another alloy. Approximately 130 centimetres across, 85 from front edge to back and 30cm/1 inch deep, it would fit in a uniform pocket. £152, 691 was raised and manufacturing of the boxes began. Although originally meant for ‘every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front’ on Christmas Day 1914, this was widened to include anyone serving, wearing the King’s uniform on Christmas Day. About 400,000 were distributed before or at Christmas, though the tally eventually reached 2.5 million, although many of those weren’t distributed until 1920, after the war was over. ‘Serving’ is appropriate, as I remember, as a child, a ‘christmas box’ was something given to tradespeople, postmen, anyone who had served you well during the year preceding.

£152, 691 was raised and manufacturing of the boxes began. Although originally meant for ‘every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front’ on Christmas Day 1914, this was widened to include anyone serving, wearing the King’s uniform on Christmas Day. About 400,000 were distributed before or at Christmas, though the tally eventually reached 2.5 million, although many of those weren’t distributed until 1920, after the war was over. ‘Serving’ is appropriate, as I remember, as a child, a ‘christmas box’ was something given to tradespeople, postmen, anyone who had served you well during the year preceding. ‘Imperium Britannicus’ and below her a lozenge bearing the inscription ‘Christmas 1914’.

‘Imperium Britannicus’ and below her a lozenge bearing the inscription ‘Christmas 1914’. First at the famed

First at the famed  fabulous side room wall-papered with posters of previous performers. It’s terrifically nostalgic and much time was spent spotting bands we recognised or knew from more youthful days. Zelda Rhiando, herself a published writer and the organiser of the Jam, was there to calm our nerves and point out the beers in the little fridge and the bottles of wine. I swore not to touch a drop before I went on.

fabulous side room wall-papered with posters of previous performers. It’s terrifically nostalgic and much time was spent spotting bands we recognised or knew from more youthful days. Zelda Rhiando, herself a published writer and the organiser of the Jam, was there to calm our nerves and point out the beers in the little fridge and the bottles of wine. I swore not to touch a drop before I went on. Brixton Book Jam was not my only interesting night on the town. Only three days later I attended the first meeting of the London chapter of the

Brixton Book Jam was not my only interesting night on the town. Only three days later I attended the first meeting of the London chapter of the  out of the prison down to the prison hulks moored on the Thames. They would then be removed to the transportation ships bound for Australia. The pub was, Anthony informed us, one of the most haunted in London. But the writers’ imaginations were already hard at work and one of us was already speculating aloud about a crime plot using the tunnels. This is, I guess, the sort of thing that happens when a group of Crime Writers gets together. I’ll be looking forward to the next meeting.

out of the prison down to the prison hulks moored on the Thames. They would then be removed to the transportation ships bound for Australia. The pub was, Anthony informed us, one of the most haunted in London. But the writers’ imaginations were already hard at work and one of us was already speculating aloud about a crime plot using the tunnels. This is, I guess, the sort of thing that happens when a group of Crime Writers gets together. I’ll be looking forward to the next meeting. I hadn’t appreciated the level of sophistication of the dwellers in this land from about 6,000 to 4,000 years ago. The world-view of the earliest, revolving around nature and the seasons, like many hunter-gatherer people, was shared across northern Europe. Of course, until about 6500 BCE and the rising of post Ice Age sea levels, the UK was part of the landmass of that continent. Although subsequently an island archipelago, the peoples who lived here had regular contact with their counterparts on the mainland. This can be seen in their art and craftwork, but also measured by their DNA. One of the most striking examples of this was of the Amesbury Archer. Bones belonging to this man, buried with his bow, were DNA tested. He was originally from the southern Alpine region, though he had lived in southern England for most of his life. Near his grave is that of another, younger man who shares the first’s DNA and is likely to have been his grandson. This man was born and lived most of his life in the Alps, but he was clearly in Amesbury when he met his end. A family visit? Or did the grandson come to live with his grandparents?

I hadn’t appreciated the level of sophistication of the dwellers in this land from about 6,000 to 4,000 years ago. The world-view of the earliest, revolving around nature and the seasons, like many hunter-gatherer people, was shared across northern Europe. Of course, until about 6500 BCE and the rising of post Ice Age sea levels, the UK was part of the landmass of that continent. Although subsequently an island archipelago, the peoples who lived here had regular contact with their counterparts on the mainland. This can be seen in their art and craftwork, but also measured by their DNA. One of the most striking examples of this was of the Amesbury Archer. Bones belonging to this man, buried with his bow, were DNA tested. He was originally from the southern Alpine region, though he had lived in southern England for most of his life. Near his grave is that of another, younger man who shares the first’s DNA and is likely to have been his grandson. This man was born and lived most of his life in the Alps, but he was clearly in Amesbury when he met his end. A family visit? Or did the grandson come to live with his grandparents? beautiful. Perfectly carved and turned stones, with elaborate patterning, these weren’t to be used for everyday, but were ceremonial and included in burials. I was fascinated by one aspect of that early culture, that ‘art’ lay in the act of creation, not, or not only, in the item produced by it. Thus, things did not have the same value as the ability to create them, which seems an eminently sensible value system to me. There is also a wonderful, finely wrought golden collar from this era. Gold was used, not because it had any intrinsic value, but because it was the colour of and reflected the light from, the sun.

beautiful. Perfectly carved and turned stones, with elaborate patterning, these weren’t to be used for everyday, but were ceremonial and included in burials. I was fascinated by one aspect of that early culture, that ‘art’ lay in the act of creation, not, or not only, in the item produced by it. Thus, things did not have the same value as the ability to create them, which seems an eminently sensible value system to me. There is also a wonderful, finely wrought golden collar from this era. Gold was used, not because it had any intrinsic value, but because it was the colour of and reflected the light from, the sun. The exhibition explains, through artefacts, how that culture changed, with the introduction of farming and a concentration on animals and other aspects of nature as a commodity. Art was still relatively fluid, in that stone carvings were made outside and weren’t ‘finished’ objects, but people added to them all the time. This is also true of Stonehenge itself. The landscape in which it was built was already crossed by ceremonial ditches and banks and, after the great sarsen stones were raised, carved on mortice and tenon principles ( see photograph, left) it was added to years later with blue stones brought from Wales, over 220 miles away.

The exhibition explains, through artefacts, how that culture changed, with the introduction of farming and a concentration on animals and other aspects of nature as a commodity. Art was still relatively fluid, in that stone carvings were made outside and weren’t ‘finished’ objects, but people added to them all the time. This is also true of Stonehenge itself. The landscape in which it was built was already crossed by ceremonial ditches and banks and, after the great sarsen stones were raised, carved on mortice and tenon principles ( see photograph, left) it was added to years later with blue stones brought from Wales, over 220 miles away. on Troy. This exhibition places the British pieces in that cross-cultural context, with a collection of armour, roughly contemporaneous to the Illiad and not dissimilar to that worn in ancient Greece (though the helmets look more like Janissaries). There were also exquisite golden drinking bowls and fine copper horsehead artefacts (the horse featured strongly as did the snake, the bird and the sun and moon ). This was a culture close to nature, even when that nature was largely tamed.

on Troy. This exhibition places the British pieces in that cross-cultural context, with a collection of armour, roughly contemporaneous to the Illiad and not dissimilar to that worn in ancient Greece (though the helmets look more like Janissaries). There were also exquisite golden drinking bowls and fine copper horsehead artefacts (the horse featured strongly as did the snake, the bird and the sun and moon ). This was a culture close to nature, even when that nature was largely tamed. the time of the lunar month. This shows a level of sophistication in understanding of the movement of the stars and planets which is reinforced when one sees how many barrows and henges were aligned with sun and, or, moon. The exhibition ranges across many of these, from Denmark, Ireland, the islands of Scotland as well as Wales, Spain, France and elsewhere in England. It also shows how the sea began to play a greater and greater role in the culture of the people living here, as trading took place and the sea itself became a place to worship. There is a recreation of the remarkable Seahenge discovered in the saltmarsh of the Norfolk coast and which, incidentally, features in the crime fiction of Elly Griffiths’ Ruth Galloway books.

the time of the lunar month. This shows a level of sophistication in understanding of the movement of the stars and planets which is reinforced when one sees how many barrows and henges were aligned with sun and, or, moon. The exhibition ranges across many of these, from Denmark, Ireland, the islands of Scotland as well as Wales, Spain, France and elsewhere in England. It also shows how the sea began to play a greater and greater role in the culture of the people living here, as trading took place and the sea itself became a place to worship. There is a recreation of the remarkable Seahenge discovered in the saltmarsh of the Norfolk coast and which, incidentally, features in the crime fiction of Elly Griffiths’ Ruth Galloway books.