As readers of Plague will know London hosts many a Roman remnant, from the baths beneath the West End to the Temple of Mithras underneath the Bank of England, but on Friday last I went to see those currently on show at the British Museum in the exhibition Nero: the man behind the myth.

As readers of Plague will know London hosts many a Roman remnant, from the baths beneath the West End to the Temple of Mithras underneath the Bank of England, but on Friday last I went to see those currently on show at the British Museum in the exhibition Nero: the man behind the myth.

This is one of the BM’s current large exhibitions showcasing their collection of Roman art and artefacts, together with pieces from Italy, Paris and other parts of the UK. It certainly tries to challenge the pervading image of Nero, the callous and brutal Caesar who fiddled while Rome burned, who persecuted the Christians, committed incest and matricide and kicked his pregnant wife to death. Only some of this is true. Nero certainly persecuted Christians – he blamed them for the great fire which raged for nine days – but he wasn’t alone in doing so. He did commit murders, at least indirectly – first century Roman palace power plays were brutal and murderous. There is evidence, however, that he cared about the people of the city – he instigated relief efforts after the Great Fire, offering shelter in his own palaces and organising food supplies and he started a very large rebuilding programme soon after. It’s almost certain that he was innocent of initiating the fire. The plebs certainly thought better of him than their Senatorial ‘betters’, Nero’s is the imperial name most often found in positive ancient graffiti. He improved the road to Ostia, Rome’s harbour where the grain shipments arrived, so as to protect the city’s food supply and insisted that the rebuilt Rome had better standards of housing. So, not all bad then.

for nine days – but he wasn’t alone in doing so. He did commit murders, at least indirectly – first century Roman palace power plays were brutal and murderous. There is evidence, however, that he cared about the people of the city – he instigated relief efforts after the Great Fire, offering shelter in his own palaces and organising food supplies and he started a very large rebuilding programme soon after. It’s almost certain that he was innocent of initiating the fire. The plebs certainly thought better of him than their Senatorial ‘betters’, Nero’s is the imperial name most often found in positive ancient graffiti. He improved the road to Ostia, Rome’s harbour where the grain shipments arrived, so as to protect the city’s food supply and insisted that the rebuilt Rome had better standards of housing. So, not all bad then.

I try and preserve a fair degree of scepticism about the common myths attaching to historical figures, preferring to  look at the historical sources. That Nero was ruthless and brutal – well, which Emperor could have ruled Rome for fourteen tumultuous years if he hadn’t been? That he ‘fiddled while Rome burned’ or at least played a lyre, comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio, historians writing during the age of later emperors and whose interests were served by making their masters look good in comparison. Tacitus, who was actually alive at the time of the fire, places Nero outside Rome when the fire happened. Given the title of the exhibition I was hoping there would be more exploration of how and why myths like those surrounding Nero were formed and how common ‘stories’ sometimes reveal a deeper truth, but that wasn’t where this was going.

look at the historical sources. That Nero was ruthless and brutal – well, which Emperor could have ruled Rome for fourteen tumultuous years if he hadn’t been? That he ‘fiddled while Rome burned’ or at least played a lyre, comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio, historians writing during the age of later emperors and whose interests were served by making their masters look good in comparison. Tacitus, who was actually alive at the time of the fire, places Nero outside Rome when the fire happened. Given the title of the exhibition I was hoping there would be more exploration of how and why myths like those surrounding Nero were formed and how common ‘stories’ sometimes reveal a deeper truth, but that wasn’t where this was going.

It’s also the case that kicking one’s pregnant wife to death was something of a literary trope in the ancient world, as signifying not just brutal cruelty but also how self-destructive mad tyrants tended to be, destroying their own offspring in their rage. So King Cambyses of Persia is said to have kicked his pregnant wife in her stomach and Periander, the Corinthian tyrant, supposedly did the same. Nero, it seems, may have been bad-mouthed in the same way.

One story I’ve come across, though I’m not sure how true it is, is about his meeting with the Pythia of Delphi. Nero toured Greece in CE 66/67 when he granted the Greeks their ‘freedom’ ( largely from the steep taxes Rome imposed upon client peoples ) and took part in the Isthmian Games. Like anyone who was anyone in the ancient world, he went to Delphi. The Pythia forbade his entry to the Temple of Apollo, calling him a matricide and telling him that the number 73 would mark the hour of his downfall. He had her burned alive ( or so Dio Cassius says ) but took her words to mean that he would live until a ripe old age. In fact he was deposed only a year or so later, by the general, later Emperor, Galba, who happened to be 73 years old at the time ( or so the story goes ). What to take from this, other than not to cross a pythia, I’m not at all sure, but then, all stories about the Pythia tend to show how she was right in the end. Not much consolation when you’re killed horribly. It makes the murder in Oracle look tame in comparison.

One story I’ve come across, though I’m not sure how true it is, is about his meeting with the Pythia of Delphi. Nero toured Greece in CE 66/67 when he granted the Greeks their ‘freedom’ ( largely from the steep taxes Rome imposed upon client peoples ) and took part in the Isthmian Games. Like anyone who was anyone in the ancient world, he went to Delphi. The Pythia forbade his entry to the Temple of Apollo, calling him a matricide and telling him that the number 73 would mark the hour of his downfall. He had her burned alive ( or so Dio Cassius says ) but took her words to mean that he would live until a ripe old age. In fact he was deposed only a year or so later, by the general, later Emperor, Galba, who happened to be 73 years old at the time ( or so the story goes ). What to take from this, other than not to cross a pythia, I’m not at all sure, but then, all stories about the Pythia tend to show how she was right in the end. Not much consolation when you’re killed horribly. It makes the murder in Oracle look tame in comparison.

And the exhibition? It is about such an interesting period in classical history and the Julio-Claudians were such a fascinating bunch, they still exert a celebrity-style, dark and seductive glamour even today, that it’s engaging. Some of the exhibits are exquisite – the jewellery, for example, or gruesome – the heavy slave chains, or the gladiator armour and the visitor forms a more rounded picture of the emperor, much more nuanced than the popular myth would have us believe. A good exhibition, worth visiting, that will make you reassess your understanding of Nero, but prepare to concentrate, there are a lot of coins.

fascinating bunch, they still exert a celebrity-style, dark and seductive glamour even today, that it’s engaging. Some of the exhibits are exquisite – the jewellery, for example, or gruesome – the heavy slave chains, or the gladiator armour and the visitor forms a more rounded picture of the emperor, much more nuanced than the popular myth would have us believe. A good exhibition, worth visiting, that will make you reassess your understanding of Nero, but prepare to concentrate, there are a lot of coins.

The exhibition at the British Museum runs until 24th October and costs £22 full price entry without donation.

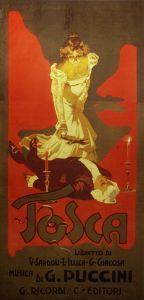

Is it entirely coincidental that, at a time when I’m working on ‘Opera’, the next novel in the Cassandra Fortune series, I’m going to more opera than usual? No, of course not. The opera in ‘Opera’ is Tosca, Puccini’s ‘shabby little shocker’ (according to musicologist Joseph Kerman) set in Rome on 17th and 18th June 1800. The dating is precise because the plot is impacted by specific events, in particular the outcome, for some time in doubt, of the Battle of Marengo then taking place far to the north. The date of events in ‘Opera’ is precise too, though opera and novel have more in common than that. Both have a political backdrop of democracy under siege by the forces of repression and wealth, both have an arch-villain and a courageous heroine. I’m off to see ENO present this later in the summer.

Is it entirely coincidental that, at a time when I’m working on ‘Opera’, the next novel in the Cassandra Fortune series, I’m going to more opera than usual? No, of course not. The opera in ‘Opera’ is Tosca, Puccini’s ‘shabby little shocker’ (according to musicologist Joseph Kerman) set in Rome on 17th and 18th June 1800. The dating is precise because the plot is impacted by specific events, in particular the outcome, for some time in doubt, of the Battle of Marengo then taking place far to the north. The date of events in ‘Opera’ is precise too, though opera and novel have more in common than that. Both have a political backdrop of democracy under siege by the forces of repression and wealth, both have an arch-villain and a courageous heroine. I’m off to see ENO present this later in the summer. nobleman who is condemned to Hell for impersonating a dead man in order to acquire his property (including an ass). The company, St Paul’s Opera, is based at a Clapham church. It was set up by Patrician Ninian and others (who have since moved on) with the specific aim of offering accessible opera while encouraging and supporting aspiring young professional singers. Some of the finest were singing last week. It was, as it always is, a sell-out.

nobleman who is condemned to Hell for impersonating a dead man in order to acquire his property (including an ass). The company, St Paul’s Opera, is based at a Clapham church. It was set up by Patrician Ninian and others (who have since moved on) with the specific aim of offering accessible opera while encouraging and supporting aspiring young professional singers. Some of the finest were singing last week. It was, as it always is, a sell-out. company who were to appear later in the opera.

company who were to appear later in the opera. and walked down to the amphitheatre. What a joy it was to be part of a happy crowd of people again, all anticipating more fun to come.

and walked down to the amphitheatre. What a joy it was to be part of a happy crowd of people again, all anticipating more fun to come. Readers of Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy will already be familiar with the alternative reality Jericho, the canal basin where the Gyptians live in Northern Lights. In real life Pullman has been an advocate in support of the residential boaters fight to save the Castlemill Boatyard in the actual Jericho from property developers. It’s that bohemian, formerly working class quarter of Oxford, bounded by the Oxford Canal, Worcester College, Walton Street and Walton Well Road. On Sunday it was host to the Jericho Book Fair, the very first post-lockdown book fair in the country, the organisers claimed. I went along.

Readers of Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy will already be familiar with the alternative reality Jericho, the canal basin where the Gyptians live in Northern Lights. In real life Pullman has been an advocate in support of the residential boaters fight to save the Castlemill Boatyard in the actual Jericho from property developers. It’s that bohemian, formerly working class quarter of Oxford, bounded by the Oxford Canal, Worcester College, Walton Street and Walton Well Road. On Sunday it was host to the Jericho Book Fair, the very first post-lockdown book fair in the country, the organisers claimed. I went along. itself was dry and plenty of people came out. There were lots of interesting stalls (I managed to buy as many books as I sold, including a 1956 Penguin Classics original edition of The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham and a more recent volume of Euripides). Oxford University Press were there, Blackwell’s Books and several other presses, as well as the Oxford Indie Book Fair.

itself was dry and plenty of people came out. There were lots of interesting stalls (I managed to buy as many books as I sold, including a 1956 Penguin Classics original edition of The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham and a more recent volume of Euripides). Oxford University Press were there, Blackwell’s Books and several other presses, as well as the Oxford Indie Book Fair. (below) writer of one of my favourite comedy spy novels A Very Important Teapot. Steve lives in nearby Bampton and has just finished writing the sequel, Bored to Death in the Baltics, which involves herring, apparently and will be published in September. He had foregone the pleasure of umpiring for his local cricket team to come along and talk about books. Sylvia Vetta, another Claret author, was on the Oxford Indie Book Festival stand (she is one of its organisers) but we had time for a chat. Sylvia’s most recent novel Sculpting the Elephant is set, in part, in Jericho where one of the main characters has an antiques business.

(below) writer of one of my favourite comedy spy novels A Very Important Teapot. Steve lives in nearby Bampton and has just finished writing the sequel, Bored to Death in the Baltics, which involves herring, apparently and will be published in September. He had foregone the pleasure of umpiring for his local cricket team to come along and talk about books. Sylvia Vetta, another Claret author, was on the Oxford Indie Book Festival stand (she is one of its organisers) but we had time for a chat. Sylvia’s most recent novel Sculpting the Elephant is set, in part, in Jericho where one of the main characters has an antiques business. approached, various purveyors of food arrived. We, on the other hand, headed off along the canal towpath to walk to Wolvercote and The Plough Inn, a walk of about an hour. We had worked up quite an appetite before we came upon a sign to our destination thoughtfully provided for folk doing just as we were. The Plough is an unusual pub in that it has its own library, which seemed very appropriate, (as well as providing good pub grub at modest prices and real ale). We sat outside, eating, drinking and watching the muntjac playing before returning to the Fair, where things were in full swing.

approached, various purveyors of food arrived. We, on the other hand, headed off along the canal towpath to walk to Wolvercote and The Plough Inn, a walk of about an hour. We had worked up quite an appetite before we came upon a sign to our destination thoughtfully provided for folk doing just as we were. The Plough is an unusual pub in that it has its own library, which seemed very appropriate, (as well as providing good pub grub at modest prices and real ale). We sat outside, eating, drinking and watching the muntjac playing before returning to the Fair, where things were in full swing. Karen, the young lady from Ghana doing work experience with Claret Press, looked like she was enjoying herself and sales were being made as people were swaying along to a set by a quartet playing guitar, banjo, mouth organ and drums. There was much chat about books, what people liked to read, what they were reading at the moment and what could be found on the other book stalls at the Fair. I did a final swing around the other stalls (spending even more money. but buying only useful things, of course) before it was time to start packing everything away and heading off to the little village of Kennington for an early supper.

Karen, the young lady from Ghana doing work experience with Claret Press, looked like she was enjoying herself and sales were being made as people were swaying along to a set by a quartet playing guitar, banjo, mouth organ and drums. There was much chat about books, what people liked to read, what they were reading at the moment and what could be found on the other book stalls at the Fair. I did a final swing around the other stalls (spending even more money. but buying only useful things, of course) before it was time to start packing everything away and heading off to the little village of Kennington for an early supper. of dreaming spires behind, to return to the Great Wen. It was on the outskirts of north London that we encountered a torrential storm, with cars aquaplaning across the traffic lanes and drivers electing to drive in single file around roundabouts. Anyone familiar with London drivers will realise just how severe the weather conditions must have been to prompt such behaviour. Nonetheless, I arrived home, tired but happy, as they say, and only a little wet from my dash to the front door. I look forward to repeating the experience next year, when I want to go inside St Barnabas Church and explore the area rather more.

of dreaming spires behind, to return to the Great Wen. It was on the outskirts of north London that we encountered a torrential storm, with cars aquaplaning across the traffic lanes and drivers electing to drive in single file around roundabouts. Anyone familiar with London drivers will realise just how severe the weather conditions must have been to prompt such behaviour. Nonetheless, I arrived home, tired but happy, as they say, and only a little wet from my dash to the front door. I look forward to repeating the experience next year, when I want to go inside St Barnabas Church and explore the area rather more. Clapham’s quirky and much-loved literary festival is back for 2021, taking place on 16 October. It will feature events in a variety of formats, including literary walks and livestreaming of events as well as the usual live author discussions. This year will also see a number of online literary events during the summer and autumn in the lead up to the event in October, which will be delivered in partnership with Time & Leisure Magazine.

Clapham’s quirky and much-loved literary festival is back for 2021, taking place on 16 October. It will feature events in a variety of formats, including literary walks and livestreaming of events as well as the usual live author discussions. This year will also see a number of online literary events during the summer and autumn in the lead up to the event in October, which will be delivered in partnership with Time & Leisure Magazine. around the literary sites of Clapham led by local authors, including the novelist and award-winning short story writer Annemarie Neary and crime fiction writer, Julie Anderson. Clapham has a long and illustrious literary history and this is a unique way of exploring it, but ticket numbers are limited so be sure to get yours early. Although we cannot be sure what level of restrictions will apply in October, if any, the walks will take place regardless of all but the strictest of lock-down circumstances.”

around the literary sites of Clapham led by local authors, including the novelist and award-winning short story writer Annemarie Neary and crime fiction writer, Julie Anderson. Clapham has a long and illustrious literary history and this is a unique way of exploring it, but ticket numbers are limited so be sure to get yours early. Although we cannot be sure what level of restrictions will apply in October, if any, the walks will take place regardless of all but the strictest of lock-down circumstances.” newspaper, will be discussing his most recent book Agent Sonya, a biography of Soviet agent, Ursula Kuszinsky and trading stories of legendary spies with local author and broadcaster Simon Berthon.

newspaper, will be discussing his most recent book Agent Sonya, a biography of Soviet agent, Ursula Kuszinsky and trading stories of legendary spies with local author and broadcaster Simon Berthon. & Leisure Magazine. This is a new departure for the Festival. It will bring high quality author interviews, often with local authors or writers connected with Clapham and south London to a wider audience all year round. Panel discussions and conversations are planned. The first of these, with best-selling local author Elizabeth Buchan, whose new book Two Women of Rome was published in June, will be taking place on 28 July. Elizabeth will be discussing her work, the settings for her books and the importance of history in her books. This is a free event to inaugurate the programme but please register at Eventbrite

& Leisure Magazine. This is a new departure for the Festival. It will bring high quality author interviews, often with local authors or writers connected with Clapham and south London to a wider audience all year round. Panel discussions and conversations are planned. The first of these, with best-selling local author Elizabeth Buchan, whose new book Two Women of Rome was published in June, will be taking place on 28 July. Elizabeth will be discussing her work, the settings for her books and the importance of history in her books. This is a free event to inaugurate the programme but please register at Eventbrite  1992 is an important year in Australian law and history because the High Court of Australia delivered a landmark ruling known as the ‘Mabo decision’. This overturned the legal concept of ‘terra nullius’ – land belonging to nobody – which was used to justify taking over the land, occupied for thousands of years by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, that subsequently became known as Australia. Eddie Koiki Mabo was a Torres Strait Islander, a Meriam man, who, along with other Islanders, filed a claim in the High Court for native title to portions of Mer Island. After ten years, on 3rd June 1992, the High Court found for Eddie, who had died of cancer five months earlier. 3rd June is celebrated as ‘Mabo Day’ in the Torres Strait Islands and there is an ongoing campaign to make it a national Australian holiday. This exhibition looks at artworks inspired by the relationship between land and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people, sometimes created in response to land disputes and colonialism.

1992 is an important year in Australian law and history because the High Court of Australia delivered a landmark ruling known as the ‘Mabo decision’. This overturned the legal concept of ‘terra nullius’ – land belonging to nobody – which was used to justify taking over the land, occupied for thousands of years by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, that subsequently became known as Australia. Eddie Koiki Mabo was a Torres Strait Islander, a Meriam man, who, along with other Islanders, filed a claim in the High Court for native title to portions of Mer Island. After ten years, on 3rd June 1992, the High Court found for Eddie, who had died of cancer five months earlier. 3rd June is celebrated as ‘Mabo Day’ in the Torres Strait Islands and there is an ongoing campaign to make it a national Australian holiday. This exhibition looks at artworks inspired by the relationship between land and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people, sometimes created in response to land disputes and colonialism. one sees at the very start of the exhibition on the Aitsis Map. I had understood a little about the connection between the Aboriginal people and the land, a reciprocal and custodial relationship. They do not ‘own’ it in the European sense of dividing and apportioning pieces of land, but have an ongoing cultural connection with it, which underpins their history, spiritual beliefs, language, lore, family and identity. This is inherent in the art of contemporary artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Dale Harding and John Mawurndjul ( I loved his woven female ancestor ).

one sees at the very start of the exhibition on the Aitsis Map. I had understood a little about the connection between the Aboriginal people and the land, a reciprocal and custodial relationship. They do not ‘own’ it in the European sense of dividing and apportioning pieces of land, but have an ongoing cultural connection with it, which underpins their history, spiritual beliefs, language, lore, family and identity. This is inherent in the art of contemporary artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Dale Harding and John Mawurndjul ( I loved his woven female ancestor ).

, 2004), the latter opera performed around the world. She is currently working on a piece to be performed in her native Australia. Philip Hensher is better known as a novelist, twice listed for the Man Booker Prize (The Mulberry Empire, 2002 and The Northern Clemency, 2008) but has an abiding love of opera and produced the libretto to Thomas Ades’ debut opera Powder Her Face (1995). His latest book is A Small Revolution in Germany (Fourth Estate, 2020). The discussion was marshalled by Jonathan Boardman, Vicar of St Pauls, Clapham, where the event took place.

, 2004), the latter opera performed around the world. She is currently working on a piece to be performed in her native Australia. Philip Hensher is better known as a novelist, twice listed for the Man Booker Prize (The Mulberry Empire, 2002 and The Northern Clemency, 2008) but has an abiding love of opera and produced the libretto to Thomas Ades’ debut opera Powder Her Face (1995). His latest book is A Small Revolution in Germany (Fourth Estate, 2020). The discussion was marshalled by Jonathan Boardman, Vicar of St Pauls, Clapham, where the event took place. by chance, it was he who suggested the subject of Ades’ first opera, the scandalous divorce between the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, which became Powder Her Face. He described the process as a suggestive and seductive one, the librettist leaving a trail of breadcrumbs (words) to entice the composer into following creatively and then to exceed the limitations of those words. Oakes described the process differently, more of a collaboration in joy. She took on the task of writing the libretto for an opera based on Shakespeare which was filled with particular challenges. She described the process as being like ‘walking around a monument, seeing it from different angles and bringing out its different aspects’. Should she adopt iambic pentameter, the verse form used most frequently by Shakespeare? Yet it might constrain or run directly against the meter of the music. Should she use it occasionally, or abandon it altogether? She also had a particular problem in that, in the play the heroine Miranda, daughter of Prospero, says very little. Oakes had to get inside the head of this character and give her more of a voice, bringing out her hopes and fears in order for her to act as a balance within the opera.

by chance, it was he who suggested the subject of Ades’ first opera, the scandalous divorce between the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, which became Powder Her Face. He described the process as a suggestive and seductive one, the librettist leaving a trail of breadcrumbs (words) to entice the composer into following creatively and then to exceed the limitations of those words. Oakes described the process differently, more of a collaboration in joy. She took on the task of writing the libretto for an opera based on Shakespeare which was filled with particular challenges. She described the process as being like ‘walking around a monument, seeing it from different angles and bringing out its different aspects’. Should she adopt iambic pentameter, the verse form used most frequently by Shakespeare? Yet it might constrain or run directly against the meter of the music. Should she use it occasionally, or abandon it altogether? She also had a particular problem in that, in the play the heroine Miranda, daughter of Prospero, says very little. Oakes had to get inside the head of this character and give her more of a voice, bringing out her hopes and fears in order for her to act as a balance within the opera. librettists speaking last night remain friends with the composers they had worked with, but there are some examples of the relationship between collaborators breaking down. So much so in Harrison Birtwhistle’s case that one of his librettists alleged that Birtwhistle had tried to run him down with his car! Gilbert and Sullivan cordially hated each other (though they made a lot of money together). On the other hand there have been some great collaborations between partners, like that between Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears (though Britten was, apparently, notoriously difficult to work with).

librettists speaking last night remain friends with the composers they had worked with, but there are some examples of the relationship between collaborators breaking down. So much so in Harrison Birtwhistle’s case that one of his librettists alleged that Birtwhistle had tried to run him down with his car! Gilbert and Sullivan cordially hated each other (though they made a lot of money together). On the other hand there have been some great collaborations between partners, like that between Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears (though Britten was, apparently, notoriously difficult to work with). ages, by Purcell, Handel, Gilbert & Sullivan and Britten. The young singers, Hugh Benson (tenor), Alexandra Dinwiddie (mezzo-soprano), Edwin Kaye (bass cantate) and Davidona Pittock (soprano) were from St Paul’s Opera, accompanied by pianist Elspeth Wilkes.

ages, by Purcell, Handel, Gilbert & Sullivan and Britten. The young singers, Hugh Benson (tenor), Alexandra Dinwiddie (mezzo-soprano), Edwin Kaye (bass cantate) and Davidona Pittock (soprano) were from St Paul’s Opera, accompanied by pianist Elspeth Wilkes.

I’ve recently been out and about looking at the places in London where the third book in the Cassandra Fortune series, entitled ‘Opera‘, is set. The obvious one, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, is not yet open to anyone but ticket holders to socially distanced performances ( though I have a contact there for when it opens more widely ), but there are others, less obvious and, to non-Londoners, perhaps something of a revelation. If ‘Plague‘ was set in places that we all know, even if it took you to parts of those places which are usually closed to view, or hidden, ‘Opera’ will introduce some settings which are less well-known, but, I hope, people may then visit.

I’ve recently been out and about looking at the places in London where the third book in the Cassandra Fortune series, entitled ‘Opera‘, is set. The obvious one, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, is not yet open to anyone but ticket holders to socially distanced performances ( though I have a contact there for when it opens more widely ), but there are others, less obvious and, to non-Londoners, perhaps something of a revelation. If ‘Plague‘ was set in places that we all know, even if it took you to parts of those places which are usually closed to view, or hidden, ‘Opera’ will introduce some settings which are less well-known, but, I hope, people may then visit.

Brompton is one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ Victorian cemeteries, which includes Highgate, with its graves of Karl Marx, George Eliot and other very famous people and Kelsall Green with its oft-filmed catacombs. While well known to locals – and a godsend during lockdowns – it is less widely known than these others. Both Kelsall Green and Tower Hamlets ( another Magnificent Seven cemetery ) featured in ‘Plague’. Brompton is owned by the Crown and run by The Royal Parks and includes many military graves, including of Commonwealth service personnel maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and many Czechoslovak, Polish and Russian military burials. It is also evidence of the diversity of Victorian London, housing as it did and does, the remains of individuals ranging from Chief Long Wolf of the Ogulala Sioux nation to Johannes Zukertorte, Jewish-Polish chess grandmaster and the Keeley and Vokes families, music hall artistes and actors. Other individuals buried here include a Mr Nutkin, Mr Brock, Mr Tod, Jeremiah Fisher and Peter Rabbett – Beatrix Potter lived nearby and was known to walk in the cemetery often, did these names inspire her?

Brompton is one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ Victorian cemeteries, which includes Highgate, with its graves of Karl Marx, George Eliot and other very famous people and Kelsall Green with its oft-filmed catacombs. While well known to locals – and a godsend during lockdowns – it is less widely known than these others. Both Kelsall Green and Tower Hamlets ( another Magnificent Seven cemetery ) featured in ‘Plague’. Brompton is owned by the Crown and run by The Royal Parks and includes many military graves, including of Commonwealth service personnel maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and many Czechoslovak, Polish and Russian military burials. It is also evidence of the diversity of Victorian London, housing as it did and does, the remains of individuals ranging from Chief Long Wolf of the Ogulala Sioux nation to Johannes Zukertorte, Jewish-Polish chess grandmaster and the Keeley and Vokes families, music hall artistes and actors. Other individuals buried here include a Mr Nutkin, Mr Brock, Mr Tod, Jeremiah Fisher and Peter Rabbett – Beatrix Potter lived nearby and was known to walk in the cemetery often, did these names inspire her? The Chapel at the cemetery’s southern end wasn’t open last week, but the grand colonnade is open all year round. Built in a style aping that of St Peter’s Square in Rome, the Colonnade runs above catacombs, which were fashionable for a brief time in Victorian London ( all too brief, additional catacombs built along the west side of the cemetery were never fully occupied ). The steps down to them are very wide and shallow, mainly because the lead-lined coffins deemed necessary for catacomb interment were extremely heavy and therefore difficult for pallbearers to carry and manoeuvre. The catacombs themselves are not open to the public except on special tours and open days and the locked metal doors, with their sculpted serpentine bas reliefs offer tantalising glimpses within.

The Chapel at the cemetery’s southern end wasn’t open last week, but the grand colonnade is open all year round. Built in a style aping that of St Peter’s Square in Rome, the Colonnade runs above catacombs, which were fashionable for a brief time in Victorian London ( all too brief, additional catacombs built along the west side of the cemetery were never fully occupied ). The steps down to them are very wide and shallow, mainly because the lead-lined coffins deemed necessary for catacomb interment were extremely heavy and therefore difficult for pallbearers to carry and manoeuvre. The catacombs themselves are not open to the public except on special tours and open days and the locked metal doors, with their sculpted serpentine bas reliefs offer tantalising glimpses within. There are always interesting things happening in the world of books, book festivals and publishing, but right now many are happening as a result, direct or otherwise, of the enforced lockdown and the removal of the usual ways in which books and literature are promoted and supported. I’ve experienced this myself, with publication of not one, but two books during COVID times. Gone were the signings, the book tours, the attending of literary festivals. My publisher’s idea of handing out the first two chapters of ‘Plague’ in a small, bound leaflet at Westminster Tube station ( the book is set in part in the Palace of Westminster ) was completely stymied by the pandemic. There were few folk emerging for work in Whitehall and even fewer tourists last year and, in any case, who was going to take a leaflet from a stranger which had PLAGUE written across the top?

There are always interesting things happening in the world of books, book festivals and publishing, but right now many are happening as a result, direct or otherwise, of the enforced lockdown and the removal of the usual ways in which books and literature are promoted and supported. I’ve experienced this myself, with publication of not one, but two books during COVID times. Gone were the signings, the book tours, the attending of literary festivals. My publisher’s idea of handing out the first two chapters of ‘Plague’ in a small, bound leaflet at Westminster Tube station ( the book is set in part in the Palace of Westminster ) was completely stymied by the pandemic. There were few folk emerging for work in Whitehall and even fewer tourists last year and, in any case, who was going to take a leaflet from a stranger which had PLAGUE written across the top? Instead, book promotion has moved even further into the virtual world. I have ‘met’ lots of people online when promoting the books in this way, people who I now think of as friends, even if I’ve never actually met them. I have invitations to Edinburgh, Newcastle and Tamworth and supporters of myself and my books across the globe, not just the book shops of south east England. I also have a network of friendly fellow authors, with whom I have appeared on panel discussions and other platforms or have coincided online with for other reasons. And I ‘know’ a host of folk via Facebook, a medium I hadn’t really used at all until very recently, but which, in COVID-times, has provided a host of alternative ‘communities’ for bookish folk – writers and readers.

Instead, book promotion has moved even further into the virtual world. I have ‘met’ lots of people online when promoting the books in this way, people who I now think of as friends, even if I’ve never actually met them. I have invitations to Edinburgh, Newcastle and Tamworth and supporters of myself and my books across the globe, not just the book shops of south east England. I also have a network of friendly fellow authors, with whom I have appeared on panel discussions and other platforms or have coincided online with for other reasons. And I ‘know’ a host of folk via Facebook, a medium I hadn’t really used at all until very recently, but which, in COVID-times, has provided a host of alternative ‘communities’ for bookish folk – writers and readers. Yes, much of this could have happened anyway, events like blog tours have been going for some time now, though there is a limit on the amount of time available for book promotion and certainly a limit on my publisher’s budget, but the restrictions have been a catalyst, at least for me and, I suspect, many others. As we become familiar with the technology and comfortable with the zoomed or skyped or livestreamed world new ideas spring up and take root. There are new things afoot in the world of book bloggers with live author chats, discussions between bloggers about books and with book club events – e.g. Mairéad Hearne at Swirl and Thread is hosting launches, Poppy Loves Book Club is hosting a series of online events and the lovely folk at the UK Crime Book Club host regular author chats and discussions and authors reading from their books – to name but three. These are all offering free events ( as long as you have the internet, of course ).

Yes, much of this could have happened anyway, events like blog tours have been going for some time now, though there is a limit on the amount of time available for book promotion and certainly a limit on my publisher’s budget, but the restrictions have been a catalyst, at least for me and, I suspect, many others. As we become familiar with the technology and comfortable with the zoomed or skyped or livestreamed world new ideas spring up and take root. There are new things afoot in the world of book bloggers with live author chats, discussions between bloggers about books and with book club events – e.g. Mairéad Hearne at Swirl and Thread is hosting launches, Poppy Loves Book Club is hosting a series of online events and the lovely folk at the UK Crime Book Club host regular author chats and discussions and authors reading from their books – to name but three. These are all offering free events ( as long as you have the internet, of course ). Some things will never be the same again I suspect. Livestreaming, a lifeline for dark theatres and closed halls, is here to stay for performance generally, reaching wider, more dispersed audiences. Many festivals of all kinds, including Clapham Book Festival, will offer livestreaming alternatives alongside live events. Our partners, Omnibus Theatre certainly plans to do so. All of which is a boon to those who would not be able to attend events like this in the normal course of things, the infirm or elderly, or those living in isolated, or culturally deprived, locations. They can now not just watch but contribute to and take part in events – which would have been unthinkable before. None of the libraries I’ve done sessions for, sometimes structured ‘talks’, sometimes conversations, plan to retreat from these online events, though they will return to providing ‘live’ ones too. Let’s hope that they’re staffed to do so. Festivals too are going online. And the Clapham Book festival is no exception – more news on that in due course.

Some things will never be the same again I suspect. Livestreaming, a lifeline for dark theatres and closed halls, is here to stay for performance generally, reaching wider, more dispersed audiences. Many festivals of all kinds, including Clapham Book Festival, will offer livestreaming alternatives alongside live events. Our partners, Omnibus Theatre certainly plans to do so. All of which is a boon to those who would not be able to attend events like this in the normal course of things, the infirm or elderly, or those living in isolated, or culturally deprived, locations. They can now not just watch but contribute to and take part in events – which would have been unthinkable before. None of the libraries I’ve done sessions for, sometimes structured ‘talks’, sometimes conversations, plan to retreat from these online events, though they will return to providing ‘live’ ones too. Let’s hope that they’re staffed to do so. Festivals too are going online. And the Clapham Book festival is no exception – more news on that in due course. City Children in 1976 and the charity now owns three farms in Wales, Devon and Gloucestershire. His most famous work is probably War Horse, which was adapted for the stage and became the most successful National Theatre production ever, being seen by over ten million people worldwide. It was made into a cinema film, directed by Stephen Spielberg, in 2011. He recently presented the Radio 4 series ‘Folk Journeys’ in which he considered some of the greatest songs ever composed. Sir Michael’s latest book is When Fishes Flew, illustrated by George Butler, to be published this Autumn.

City Children in 1976 and the charity now owns three farms in Wales, Devon and Gloucestershire. His most famous work is probably War Horse, which was adapted for the stage and became the most successful National Theatre production ever, being seen by over ten million people worldwide. It was made into a cinema film, directed by Stephen Spielberg, in 2011. He recently presented the Radio 4 series ‘Folk Journeys’ in which he considered some of the greatest songs ever composed. Sir Michael’s latest book is When Fishes Flew, illustrated by George Butler, to be published this Autumn. Ben Macintyre is an author, historian, reviewer and columnist for The Times newspaper. His most recent book, Agent Sonya, is a biography of Soviet agent Ursula Kuczinsky, has been acclaimed as a thriller as well as a piece of history. Both events will be livestreamed and live stream ticket holders will receive a copy of the respective author’s book. If we are in another lockdown or under other restrictions in force the event will go ahead as a livestream only, or, potentially as a zoom event.

Ben Macintyre is an author, historian, reviewer and columnist for The Times newspaper. His most recent book, Agent Sonya, is a biography of Soviet agent Ursula Kuczinsky, has been acclaimed as a thriller as well as a piece of history. Both events will be livestreamed and live stream ticket holders will receive a copy of the respective author’s book. If we are in another lockdown or under other restrictions in force the event will go ahead as a livestream only, or, potentially as a zoom event. discussion there is in each group). Ticket numbers will be limited so it’ll be important to book early. We hope the walks can take place in any circumstances but a strict lockdown.

discussion there is in each group). Ticket numbers will be limited so it’ll be important to book early. We hope the walks can take place in any circumstances but a strict lockdown. My contemporary crime fiction is set in the world of high politics ( and low sleaze ), of ministers, conferences, lobbyists and business interests. Activists of various kind also feature, particularly in Oracle. In that book a contemporary political issue also impacts upon the plot; the politicisation of the police. This is specifically regarding the Greek criminal organisation Golden Dawn, which formerly styled itself a political party and to which many police belonged in the real world. There are other examples of politics intruding on police work, most notably in the U.S., where former President Trump deployed ‘private’ police forces funded with federal money in cities where demonstrations were taking place ( see pic left ). A ‘defund the police’ movement began as a result of this and of the repeated deaths in custody of black people. So far, so scary.

My contemporary crime fiction is set in the world of high politics ( and low sleaze ), of ministers, conferences, lobbyists and business interests. Activists of various kind also feature, particularly in Oracle. In that book a contemporary political issue also impacts upon the plot; the politicisation of the police. This is specifically regarding the Greek criminal organisation Golden Dawn, which formerly styled itself a political party and to which many police belonged in the real world. There are other examples of politics intruding on police work, most notably in the U.S., where former President Trump deployed ‘private’ police forces funded with federal money in cities where demonstrations were taking place ( see pic left ). A ‘defund the police’ movement began as a result of this and of the repeated deaths in custody of black people. So far, so scary. tarnished. In the US the Vietnam War, in the UK the three-day week and ‘the sick man of Europe’ made for a more sceptical and hard boiled sensibility. The Day of the Jackal, The Andromeda Strain, Six Days of the Condor are three crime/conspiracy novels, turned into major films, which spring to mind. Then there was police corruption, found in crime fiction like Lawrence Block’s NYPD stories, Leonardo Sciascia in Sicily ( long before Montalbano ) or countless Hollywood films, the Dirty Harry movies, Serpico, The French Connection. Is the politicisation of the police going to be something similar?

tarnished. In the US the Vietnam War, in the UK the three-day week and ‘the sick man of Europe’ made for a more sceptical and hard boiled sensibility. The Day of the Jackal, The Andromeda Strain, Six Days of the Condor are three crime/conspiracy novels, turned into major films, which spring to mind. Then there was police corruption, found in crime fiction like Lawrence Block’s NYPD stories, Leonardo Sciascia in Sicily ( long before Montalbano ) or countless Hollywood films, the Dirty Harry movies, Serpico, The French Connection. Is the politicisation of the police going to be something similar? having the politics of policing threaded though it (as it happens these also arose during a discussion I had on Sunday ). Then a series I had never heard of but will definitely try – Ausma Zehanat Khan’s duo detectives Esa Khattak and Rachel Getty. Khan is a British born Canadian and now lives in the U.S. and her pair are Community Police Officers in Toronto, but the books range across the world. One series I remembered as soon as it was suggested was the Law & Order TV series based on four plays by G F Newman, which were also published as books A Detective’s Tale, A Villain’s Tale and A Prisoner’s Tale. HarperCollins reprinted them in an omnibus edition in 1984. These were controversial at the time, as they depicted a corrupt UK policing and legal system and shouldn’t be confused with the US TV series of that name. The UK series was altogether harder and grittier and caused ructions. As did Newman’s later Crime and Punishment, which involved a criminal bankrolling the Conservative party ( where have I heard that before )?

having the politics of policing threaded though it (as it happens these also arose during a discussion I had on Sunday ). Then a series I had never heard of but will definitely try – Ausma Zehanat Khan’s duo detectives Esa Khattak and Rachel Getty. Khan is a British born Canadian and now lives in the U.S. and her pair are Community Police Officers in Toronto, but the books range across the world. One series I remembered as soon as it was suggested was the Law & Order TV series based on four plays by G F Newman, which were also published as books A Detective’s Tale, A Villain’s Tale and A Prisoner’s Tale. HarperCollins reprinted them in an omnibus edition in 1984. These were controversial at the time, as they depicted a corrupt UK policing and legal system and shouldn’t be confused with the US TV series of that name. The UK series was altogether harder and grittier and caused ructions. As did Newman’s later Crime and Punishment, which involved a criminal bankrolling the Conservative party ( where have I heard that before )?