So this article is a sequel. I’ve already written about how the plot of ‘Plague’ has coincided with real life, but, astonishingly, the coincidences keep coming!

There is the recent, real, discovery of hundreds of bodies, skeletons, in a lost medieval sacristy belonging to Westminster Abbey as reported in The Guardian at the weekend. Not, I know, the same as the discovery of a plague pit, with or without modern corpses, but startling nonetheless and an example of how the land around and beneath Westminster, or Thorney Island, still has secrets to divulge. Just as it does in the novel.

There is the recent, real, discovery of hundreds of bodies, skeletons, in a lost medieval sacristy belonging to Westminster Abbey as reported in The Guardian at the weekend. Not, I know, the same as the discovery of a plague pit, with or without modern corpses, but startling nonetheless and an example of how the land around and beneath Westminster, or Thorney Island, still has secrets to divulge. Just as it does in the novel.

But an even closer correlation between ‘Plague’ and what is happening now might  be what I can only call the procurement scandals. In the novel large government contracts, worth several billion pounds, are being tendered and, as one of the characters says ‘…the contracts aren’t being awarded in the usual way.’ It’s corruption – the contracts are being given to companies run by associates and accomplices of the villains, who also make money on the stock exchange as the shares of those companies rise in value. At least in the book the companies in question have the relevant expertise and a track record in providing the types of services being tendered for.

be what I can only call the procurement scandals. In the novel large government contracts, worth several billion pounds, are being tendered and, as one of the characters says ‘…the contracts aren’t being awarded in the usual way.’ It’s corruption – the contracts are being given to companies run by associates and accomplices of the villains, who also make money on the stock exchange as the shares of those companies rise in value. At least in the book the companies in question have the relevant expertise and a track record in providing the types of services being tendered for.

In real life, however, we see huge contracts being awarded to companies with little or no experience or expertise in the field of activity required, but which do have close ties to various individuals in government. The Good Law Project, together with Every Doctor, are pursuing judicial review of the procurement of PPE from  three companies, one specialising in pest control, one a confectionery wholesaler and one an opaque private fund owned via a tax haven. The PPE – face masks – sold by the last of these companies, Ayanda Capital, under a contract worth £252m, was found to be unsuitable for use in the NHS (and untested). Yet at least this contract was publicly tendered. The contracts granted to Public First, a company with close ties to Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings, seem not to have been tendered at all and The Good Law Project and a number of non-Tory MPs are seeking judicial review of the awarding of them. They have also begun proceedings against Michael Gove in regard to one of these contracts. Contrary to government regulations, the contracts themselves have not been published (once granted, contracts are required to be published within thirty days).

three companies, one specialising in pest control, one a confectionery wholesaler and one an opaque private fund owned via a tax haven. The PPE – face masks – sold by the last of these companies, Ayanda Capital, under a contract worth £252m, was found to be unsuitable for use in the NHS (and untested). Yet at least this contract was publicly tendered. The contracts granted to Public First, a company with close ties to Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings, seem not to have been tendered at all and The Good Law Project and a number of non-Tory MPs are seeking judicial review of the awarding of them. They have also begun proceedings against Michael Gove in regard to one of these contracts. Contrary to government regulations, the contracts themselves have not been published (once granted, contracts are required to be published within thirty days).

As the same ‘Plague’ character, a journalist, says ‘There’s a smell attaching to it. Lots of  money involved.’ My main character Cassie is, of course, working on minor procurement contracts at the start of the novel, but she has no enthusiasm for the work. As a former senior civil servant I sympathise with those who are having to deal with the situation now, knowing that the correct procedures aren’t being followed. It seems that Ministers are hiding behind COVID and emergency powers to hand large sums of money to preferred bidders, regardless of said bidders ability to deliver the contracts.

money involved.’ My main character Cassie is, of course, working on minor procurement contracts at the start of the novel, but she has no enthusiasm for the work. As a former senior civil servant I sympathise with those who are having to deal with the situation now, knowing that the correct procedures aren’t being followed. It seems that Ministers are hiding behind COVID and emergency powers to hand large sums of money to preferred bidders, regardless of said bidders ability to deliver the contracts.

I wonder if there will be a Stranger then Fiction III? What about those share prices? Watch this space?

For more on ‘Plague’ try Walking a book, walking a river The Bookwalk continues With an address like that you must be very wealthy

Is the thought of my heroine, Cassie, when told where another character in my novel lives. Yet, before our Bookwalk took us to look at the enviable address, we had some more medieval ground to cover, specifically the 14th century Jewel Tower. This remnant of the Abbey, which stood next to the Abbey moat, now stands on Abingdon or ‘College’ Green opposite Parliament. It is part of the Palace of Westminster, although set apart from Barry’s Victorian pile and Westminster Hall and it plays a crucial role in Plague.

Is the thought of my heroine, Cassie, when told where another character in my novel lives. Yet, before our Bookwalk took us to look at the enviable address, we had some more medieval ground to cover, specifically the 14th century Jewel Tower. This remnant of the Abbey, which stood next to the Abbey moat, now stands on Abingdon or ‘College’ Green opposite Parliament. It is part of the Palace of Westminster, although set apart from Barry’s Victorian pile and Westminster Hall and it plays a crucial role in Plague. ground which surrounds it, a testament to its great age. It is open to the public, though not at the present moment. We entertained a rather bored-looking set of professional camera men set up in their familiar interviewing place on the Green, by doing our own ‘pieces to camera’ both in front of the Jewel Tower and the Victoria Tower, one of the few parts of the Palace of Westminster not covered in scaffolding or sheeting. Returning to Parliament Square, we went past the Abbey itself and entered Great Smith Street, then Little Smith Street, into that maze of small alleyways with buildings belonging to the Abbey and the Church.

ground which surrounds it, a testament to its great age. It is open to the public, though not at the present moment. We entertained a rather bored-looking set of professional camera men set up in their familiar interviewing place on the Green, by doing our own ‘pieces to camera’ both in front of the Jewel Tower and the Victoria Tower, one of the few parts of the Palace of Westminster not covered in scaffolding or sheeting. Returning to Parliament Square, we went past the Abbey itself and entered Great Smith Street, then Little Smith Street, into that maze of small alleyways with buildings belonging to the Abbey and the Church. Great College Street was our destination, where Westminster School buildings run into the 14th century boundary wall, and under which the River Tyburn ran. It is on the corner with Barton Street where our desirable residence sits. Here we were fortunate to come across a woman who worked in the next house along, who was charmed by the thought of the neighbouring house appearing in a novel (and we think we made a sale). I hope the occupants of the actual house are equally charmed.

Great College Street was our destination, where Westminster School buildings run into the 14th century boundary wall, and under which the River Tyburn ran. It is on the corner with Barton Street where our desirable residence sits. Here we were fortunate to come across a woman who worked in the next house along, who was charmed by the thought of the neighbouring house appearing in a novel (and we think we made a sale). I hope the occupants of the actual house are equally charmed. Smith Square, are, to my mind, some of the most desirable in London. The fine Georgian town houses sit in quiet, tree-lined streets, yet are close to one of London’s ‘centres’ and the epicentre of establishment power. Many of them are still in private ownership, either as houses or apartments, though there are many school buildings at the north end and the Georgian buildings give way to corporate headquarters and government departments to the south. Marsham Street is lined with government

Smith Square, are, to my mind, some of the most desirable in London. The fine Georgian town houses sit in quiet, tree-lined streets, yet are close to one of London’s ‘centres’ and the epicentre of establishment power. Many of them are still in private ownership, either as houses or apartments, though there are many school buildings at the north end and the Georgian buildings give way to corporate headquarters and government departments to the south. Marsham Street is lined with government  buildings – the Home Office, the Department for Transport, the old DTI building, many of them linked. All lie on the route of the number 88 bus – the ‘Clapham omnibus’ – and we hopped on to it for a few stops to Pimlico, because we were running out of time (and, by now, our feet were hurting). The Pimlico which we currently see, of elegant early Victorian terraces, is predominantly the creation of the property developer Thomas Cubitt in the 1830s. In the novel it is where a

buildings – the Home Office, the Department for Transport, the old DTI building, many of them linked. All lie on the route of the number 88 bus – the ‘Clapham omnibus’ – and we hopped on to it for a few stops to Pimlico, because we were running out of time (and, by now, our feet were hurting). The Pimlico which we currently see, of elegant early Victorian terraces, is predominantly the creation of the property developer Thomas Cubitt in the 1830s. In the novel it is where a  supporting character lives, on Tachbrook Street, so named for the Tach Brook which, at this point, ran into the old River Tyburn and thence to the Thames.

supporting character lives, on Tachbrook Street, so named for the Tach Brook which, at this point, ran into the old River Tyburn and thence to the Thames. halves awaited. The day ended with a most perfect sunset over the Thames and Pimlico. A really great walk ( over seven miles of it ) and a really great day. My thanks to Helen Hughes for her photography and her company.

halves awaited. The day ended with a most perfect sunset over the Thames and Pimlico. A really great walk ( over seven miles of it ) and a really great day. My thanks to Helen Hughes for her photography and her company. imagined as well as the archaeological city. I spent several happy hours in it yesterday (and will be returning next week).

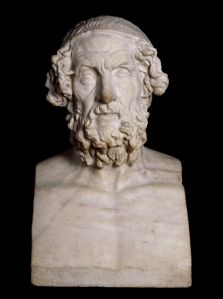

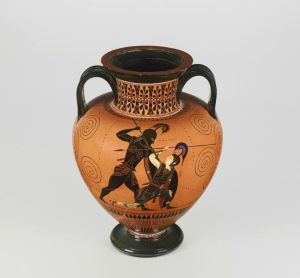

imagined as well as the archaeological city. I spent several happy hours in it yesterday (and will be returning next week). from the coloured figures, like those on the large two handled pot depicting Achilles killing Amazon Queen Penthisiliea (right) or the Judgement of Paris on a wine krater, to the delicate line drawings showing Briseis being led away from Achilles’ tent. I will also remember the stone bas relief showing this scene, with Achilles looking away in anger, but Patroclus placing a consolatory hand on Briseis’ shoulder as she is collected by Agamemnon’s soldier. A tender gesture.

from the coloured figures, like those on the large two handled pot depicting Achilles killing Amazon Queen Penthisiliea (right) or the Judgement of Paris on a wine krater, to the delicate line drawings showing Briseis being led away from Achilles’ tent. I will also remember the stone bas relief showing this scene, with Achilles looking away in anger, but Patroclus placing a consolatory hand on Briseis’ shoulder as she is collected by Agamemnon’s soldier. A tender gesture. It is testament to the power of the ancient story that the characters live so vividly again. But then, the story has been told and retold, as evidenced by the lines from the epics scribbled by ancient Roman children on the papyri copy books displayed. Its retelling is brought bang up to date with the poster from the, much derided, 21st century Hollywood film Troy and modern versions of The Judgement of Paris – photographic – and The Siren’s Song ( see left for the ancient depiction, below for the modern collage by Romare Bearden ). Aficionados of the male body please note, Brad Pitt has quite a lot of competition in the buffed masculinity stakes, though it’s interesting that, even where a ‘hero’ such as Odysseus is obviously beyond youth and is depicted on artefacts with an older face, his body is still drawn as youthfully ideal. Hollywood’s fixation with perfect bodies is nothing new.

It is testament to the power of the ancient story that the characters live so vividly again. But then, the story has been told and retold, as evidenced by the lines from the epics scribbled by ancient Roman children on the papyri copy books displayed. Its retelling is brought bang up to date with the poster from the, much derided, 21st century Hollywood film Troy and modern versions of The Judgement of Paris – photographic – and The Siren’s Song ( see left for the ancient depiction, below for the modern collage by Romare Bearden ). Aficionados of the male body please note, Brad Pitt has quite a lot of competition in the buffed masculinity stakes, though it’s interesting that, even where a ‘hero’ such as Odysseus is obviously beyond youth and is depicted on artefacts with an older face, his body is still drawn as youthfully ideal. Hollywood’s fixation with perfect bodies is nothing new. There is a very interesting section on the real city of Troy, or what we now believe is the real city. Not Schliemann’s much too early, if appropriately burnt, discovery but a later version. I didn’t realise just how many Troys there were, built on top of one another, but there are informative graphics showing just how these cities developed and when. Indeed the whole exhibition is well organised, with clearly written and illuminating captions. Technology, from the annotated drawings in light of

There is a very interesting section on the real city of Troy, or what we now believe is the real city. Not Schliemann’s much too early, if appropriately burnt, discovery but a later version. I didn’t realise just how many Troys there were, built on top of one another, but there are informative graphics showing just how these cities developed and when. Indeed the whole exhibition is well organised, with clearly written and illuminating captions. Technology, from the annotated drawings in light of  various pieces of complex decoration to help the viewer unscramble some of the detail, to the videos showing the massing levels of the different Troys is used cleverly and well.

various pieces of complex decoration to help the viewer unscramble some of the detail, to the videos showing the massing levels of the different Troys is used cleverly and well. …is what one gets at the Dennis Severs House, or 18, Folgate Street, Spitalields, E1. Not quite a fleeting glimpse of those people who have just left the room, who were eating that meal just before you walked in, or smoking that pipe, or baking that loaf. Whose wig sits on the wing of the chair? Or whose floral perfume scents the formal withdrawing room?

…is what one gets at the Dennis Severs House, or 18, Folgate Street, Spitalields, E1. Not quite a fleeting glimpse of those people who have just left the room, who were eating that meal just before you walked in, or smoking that pipe, or baking that loaf. Whose wig sits on the wing of the chair? Or whose floral perfume scents the formal withdrawing room? and storyteller, who died, aged only 51, in 1999. Twenty years after purchasing the house he saw the Spitalfields Trust buy the house and commit to keeping it going, when on his death-bed. It’s still going twenty years later.

and storyteller, who died, aged only 51, in 1999. Twenty years after purchasing the house he saw the Spitalfields Trust buy the house and commit to keeping it going, when on his death-bed. It’s still going twenty years later. inhabit the house and it is their homely detritus (and comestibles) that one comes across as one climbs the narrow stairs, either down to the kitchen and cellar, where there are the supposed fragments of St Mary’s, Spital (1197) and the warmth of an iron range and the smell of…what is that smell? Or upwards, through fashionable London entertaining to the elaborate boudoir and then up beneath the eaves to the penurious lodgers’ rooms.

inhabit the house and it is their homely detritus (and comestibles) that one comes across as one climbs the narrow stairs, either down to the kitchen and cellar, where there are the supposed fragments of St Mary’s, Spital (1197) and the warmth of an iron range and the smell of…what is that smell? Or upwards, through fashionable London entertaining to the elaborate boudoir and then up beneath the eaves to the penurious lodgers’ rooms. There are wordless guiders, who will direct you if you go wrong.

There are wordless guiders, who will direct you if you go wrong. This year’s Spring exhibition at 2, Temple Place is a collaboration with Museums Sheffield and the Guild of St George to bring together a range of paintings, drawings, metal works and plaster casts to celebrate the work and legacy of John Ruskin (1819 – 1900).

This year’s Spring exhibition at 2, Temple Place is a collaboration with Museums Sheffield and the Guild of St George to bring together a range of paintings, drawings, metal works and plaster casts to celebrate the work and legacy of John Ruskin (1819 – 1900). J.M.W.Turner and redefined art criticism of the day. It brought him to the notice of luminaries such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Charlotte Bronte. This was followed by Modern Painters II (1846) written while on the Grand Tour with his parents. He married Effie Gray, the young daughter of a family friend in 1847. Together they journeyed to Venice where Ruskin worked on perhaps his most famous three-volume work The Stones of Venice (1851-1853). It was in The Nature of Gothic chapter in Vol II that he set out his belief in artisanal integrity and attacked industrial capitalism which had such an impact on socialists like William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement.

J.M.W.Turner and redefined art criticism of the day. It brought him to the notice of luminaries such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Charlotte Bronte. This was followed by Modern Painters II (1846) written while on the Grand Tour with his parents. He married Effie Gray, the young daughter of a family friend in 1847. Together they journeyed to Venice where Ruskin worked on perhaps his most famous three-volume work The Stones of Venice (1851-1853). It was in The Nature of Gothic chapter in Vol II that he set out his belief in artisanal integrity and attacked industrial capitalism which had such an impact on socialists like William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. The marriage was, apparently, unconsummated ( though Ruskin contested this ) and was subsequently annulled in 1854, though not before major scandal when Effie left Ruskin for John Everett Millais. Ruskin had championed the Pre-Raphealites and continued to do so, even providing a stipend for Elizabeth Siddal, Rosetti’s wife, to encourage her art. He also became a firm friend of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. These friendships are documented in the exhibition, as is his late crossing of swords with James McNeill Whistler. While the case bankrupted Whistler, it also tarnished Ruskin’s reputation and may have contributed to his mental decline. I have never understood how a devotee of Turner’s art could have denigrated Whistler’s and that isn’t something which is tackled here.

The marriage was, apparently, unconsummated ( though Ruskin contested this ) and was subsequently annulled in 1854, though not before major scandal when Effie left Ruskin for John Everett Millais. Ruskin had championed the Pre-Raphealites and continued to do so, even providing a stipend for Elizabeth Siddal, Rosetti’s wife, to encourage her art. He also became a firm friend of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. These friendships are documented in the exhibition, as is his late crossing of swords with James McNeill Whistler. While the case bankrupted Whistler, it also tarnished Ruskin’s reputation and may have contributed to his mental decline. I have never understood how a devotee of Turner’s art could have denigrated Whistler’s and that isn’t something which is tackled here. Turner paintings and Durer engravings ( loved the cat ) as well as many of his own drawings and paintings. In addition there are newly commissioned pieces exploring the legacy of Ruskin, from Timorous Beasties, Grizedale Arts, Hannah Dowling and Emilie Taylor. I very much enjoyed

Turner paintings and Durer engravings ( loved the cat ) as well as many of his own drawings and paintings. In addition there are newly commissioned pieces exploring the legacy of Ruskin, from Timorous Beasties, Grizedale Arts, Hannah Dowling and Emilie Taylor. I very much enjoyed  country house and showcase for architect and collector Sir John Soane, with its attached art gallery. In the sunshine Ealing looked leafy indeed, with its Common and Green ( who knew, not me, certainly ). Still there, set back from the Uxbridge Road, the original Ealing Studios where so many classic films were made. We even found a handsome Georgian/early Victorian hostelry named The Sir Micheal Balcon, after the legendary producer and head of the studios in its heyday.

country house and showcase for architect and collector Sir John Soane, with its attached art gallery. In the sunshine Ealing looked leafy indeed, with its Common and Green ( who knew, not me, certainly ). Still there, set back from the Uxbridge Road, the original Ealing Studios where so many classic films were made. We even found a handsome Georgian/early Victorian hostelry named The Sir Micheal Balcon, after the legendary producer and head of the studios in its heyday. frontage and garden now behind a formal war memorial. Entrance gates are to the right hand side of the formal gardens. Inside it is less chaotic – less mad – than his house and museum on Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but it still demonstrates his distinct architectural style and idiosyncratic and impressive design. The interior has been meticulously restored to a very high standard, including the hand-painted and beautiful ‘chinese’ wallpaper in the gloriously light drawing room, the exquisite ceilings and ‘marbled’ walls.

frontage and garden now behind a formal war memorial. Entrance gates are to the right hand side of the formal gardens. Inside it is less chaotic – less mad – than his house and museum on Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but it still demonstrates his distinct architectural style and idiosyncratic and impressive design. The interior has been meticulously restored to a very high standard, including the hand-painted and beautiful ‘chinese’ wallpaper in the gloriously light drawing room, the exquisite ceilings and ‘marbled’ walls. employer George Dance and which Soane retained, demolishing the rest of the mansion and rebuilding it, including a colonnade of ‘ruins’, which now links the main house and the modern gallery.

employer George Dance and which Soane retained, demolishing the rest of the mansion and rebuilding it, including a colonnade of ‘ruins’, which now links the main house and the modern gallery. I loved the long glass gallery which runs across the rear of the house and overlooks what would have been the private gardens, including a lake with rusticated bridge. These have now been merged with Walpole Park (1901) a public park which includes another lake, formal gardens and a sporting pavilion. I also loved the two huge rooms in George Dance’s wing, the dining room on the ground floor and salon or drawing room on the first. I’m not surprised that Soane couldn’t bring himself to demolish this even if it means that the whole Manor has a rather lop-sided look.

I loved the long glass gallery which runs across the rear of the house and overlooks what would have been the private gardens, including a lake with rusticated bridge. These have now been merged with Walpole Park (1901) a public park which includes another lake, formal gardens and a sporting pavilion. I also loved the two huge rooms in George Dance’s wing, the dining room on the ground floor and salon or drawing room on the first. I’m not surprised that Soane couldn’t bring himself to demolish this even if it means that the whole Manor has a rather lop-sided look. the old kitchen buildings into Pitzhanger Gallery. The current exhibition is by Anish Kapoor and it complements Soane perfectly. Kapoor’s mirrored and sculpted discs and boxes play with light, vision and sound just as Soane’s interiors do, tricking the eye. The pieces are interactive and huge fun. A gallery employee told us that he saw something new in each of the pieces every day he turned up for work and took great pleasure in watching visitors play with the distortions. We certainly enjoyed doing so, taking photographs into the sculpted mirrors which captured one of us upside down in the middle ground while the other was the right way up nearer to the piece.

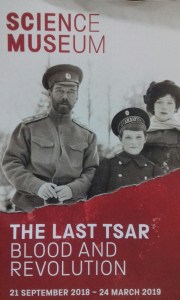

the old kitchen buildings into Pitzhanger Gallery. The current exhibition is by Anish Kapoor and it complements Soane perfectly. Kapoor’s mirrored and sculpted discs and boxes play with light, vision and sound just as Soane’s interiors do, tricking the eye. The pieces are interactive and huge fun. A gallery employee told us that he saw something new in each of the pieces every day he turned up for work and took great pleasure in watching visitors play with the distortions. We certainly enjoyed doing so, taking photographs into the sculpted mirrors which captured one of us upside down in the middle ground while the other was the right way up nearer to the piece. The Last Tsar; Blood and Revolution is the name of an interesting and FREE exhibition currently to be found at the Science Museum, Exhibition Road SW7. We visited on Monday.

The Last Tsar; Blood and Revolution is the name of an interesting and FREE exhibition currently to be found at the Science Museum, Exhibition Road SW7. We visited on Monday. diagnosed in women who behaved ‘unsuitably’ or ‘hysterically’ ). It shows how the ruling family kept the illness of the Tsaravitch, Alexei, hidden from all but an immediate circle of trusted intimates and medical men, thereby fuelling discontent among the aristocracy over the perceived remoteness of the Romanov family and influence of ‘advisers’ like Rasputin. An autocratic and fundamentally unjust system could not survive without an involved and supportive aristocracy and the myth of a benign and progressive monarchy couldn’t be sustained by a monarch invisible to his people. Not so long after the outbreak of WWI a system of government which was creaking finally broke and the Tsar abdicated.

diagnosed in women who behaved ‘unsuitably’ or ‘hysterically’ ). It shows how the ruling family kept the illness of the Tsaravitch, Alexei, hidden from all but an immediate circle of trusted intimates and medical men, thereby fuelling discontent among the aristocracy over the perceived remoteness of the Romanov family and influence of ‘advisers’ like Rasputin. An autocratic and fundamentally unjust system could not survive without an involved and supportive aristocracy and the myth of a benign and progressive monarchy couldn’t be sustained by a monarch invisible to his people. Not so long after the outbreak of WWI a system of government which was creaking finally broke and the Tsar abdicated. Ekaterinberg. The initial investigation was headed by Nikolai, Sokolov, a Russian investigating magistrate, when that city fell out of Bolshevik control, and its findings were, for a long while, the only real evidence-informed information about their deaths. Later, after the Soviet state admitted executing the family and the eventual fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, scientists were able to piece together those earlier findings with later discoveries made during the 1970s but not made public at the time, to find skeletons which could then be tested using the latest techniques.

Ekaterinberg. The initial investigation was headed by Nikolai, Sokolov, a Russian investigating magistrate, when that city fell out of Bolshevik control, and its findings were, for a long while, the only real evidence-informed information about their deaths. Later, after the Soviet state admitted executing the family and the eventual fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, scientists were able to piece together those earlier findings with later discoveries made during the 1970s but not made public at the time, to find skeletons which could then be tested using the latest techniques. Alexei and one of his sisters were discovered and also tested. Facial reconstruction and modelling techniques were then used to recreate the faces from the skulls, resulting in sculptures which closely resembled the photographs of the individuals taken while they were alive. So all eleven victims were identified and the fate of the Romanovs finally resolved.

Alexei and one of his sisters were discovered and also tested. Facial reconstruction and modelling techniques were then used to recreate the faces from the skulls, resulting in sculptures which closely resembled the photographs of the individuals taken while they were alive. So all eleven victims were identified and the fate of the Romanovs finally resolved.