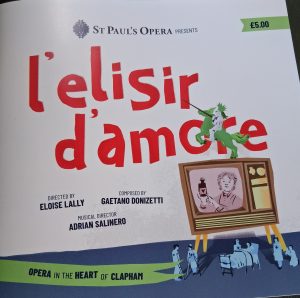

Earlier this year I was approached by Patricia Ninian of St Paul’s Opera company with the suggestion that I should work with them on their summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore by Donizetti. The director, Eloise Lally (English Touring Opera) wanted to set the production in a hospital after the second world war. Patricia had read my book, The Midnight Man and spotted the synergies immediately, especially as ‘my’ hospital was based on a real, Clapham hospital – the South London Hospital for Women and Children. I was invited to rehearsals and I began to keep a rehearsal diary, a version of which follows.

Earlier this year I was approached by Patricia Ninian of St Paul’s Opera company with the suggestion that I should work with them on their summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore by Donizetti. The director, Eloise Lally (English Touring Opera) wanted to set the production in a hospital after the second world war. Patricia had read my book, The Midnight Man and spotted the synergies immediately, especially as ‘my’ hospital was based on a real, Clapham hospital – the South London Hospital for Women and Children. I was invited to rehearsals and I began to keep a rehearsal diary, a version of which follows.

Saturday 17th May

It’s the first full day of rehearsals and Eloise Lally, the Director, sits in a front pew blocking out stage positions and movement for the chorus. Most members of the chorus are here, taking up their places and moving at the direction of Eloise. Outside the sky is blue. Sunshine makes angular shadows on the deep window embrasures.

It’s obvious that there’s been previous discussions about the setting – in the South London Hospital, Clapham during the period following the end of World War two – and its fruits are evident.

‘Is this where the bed will be?’ asks a chorus member.

‘You’re sitting on it,’ responds Eloise.

The stage is bare.

Yet there is also a television, a relative rarity in late 1940s London, but certainly possible in a hospital common room. Chorus members stare at the invisible item, transfixed by its novelty.

Individual chorus members already have characters. So, I meet Pam, a south London girl, with the accent on ‘sarf’. A middle-aged lady with lumbago, she is never seen without a cigarette in her fingers. Many chorus members are halt and lame, patients of the hospital and walking wounded. These ‘characters’ give both variation and verisimilitude to what would otherwise simply be an amorphous group.

on ‘sarf’. A middle-aged lady with lumbago, she is never seen without a cigarette in her fingers. Many chorus members are halt and lame, patients of the hospital and walking wounded. These ‘characters’ give both variation and verisimilitude to what would otherwise simply be an amorphous group.

Eloise doesn’t only place the chorus physically, but also psychologically. She tells us that all the chorus characters know that Nemorino is hopelessly in love with Adina, who is so far out of his reach. Most of them feel sorry for him. They see, at the beginning of Act 2, that the lovelorn suitor buys something from Dr Dulcamara and are curious about what. Hospitals are places where gossip and rumour often run unchecked and L’Elisir’s South London is no different.

Throughout the pianist plays and replays accompaniment and also sings the soloists parts where necessary sometimes to the amusement of the cast. She is aided in the tenor role by Edvard Adde (the Norwegian tenor, cover for the role of Nemorino).

Throughout the pianist plays and replays accompaniment and also sings the soloists parts where necessary sometimes to the amusement of the cast. She is aided in the tenor role by Edvard Adde (the Norwegian tenor, cover for the role of Nemorino).

At two o’clock we break for lunch and many of the singers head towards Clapham Common and the crowds who are enjoying the weekend sunshine, while others remain closer by in the dappled shade of the peaceful churchyard. Back to resume at three!

Saturday 24th May

It is one week and several rehearsals on and there are more singers in a rather chilly church. This time the chorus and three of the principals are here, as is the Director of Music, Adrian Salinero at the piano, as well as Eloise. Outside the sky is grey.

We go ‘from the top’ Act I, Scene I and singers enter from different parts of the church to take their places on stage. Chorus members ‘characters’ do their stage business and eventually settle down to watch the new-fangled television. Matron Adina (Dorset-born soprano, Fiona Hymns) consults with Nurse Gianetta (Isabella Roberts), then it’s straight into her first aria.

new-fangled television. Matron Adina (Dorset-born soprano, Fiona Hymns) consults with Nurse Gianetta (Isabella Roberts), then it’s straight into her first aria.

The interplay between principals and with other cast members is taking shape. Belcore (baritone, Theodore ‘Ted’ Day) is a delusional patient who imagines he is still fighting the war, he treats everyone as if they’re in his military company and the rest of the cast plays along with tolerant affection. He preens himself in preparation for his declaration of love for Adina. Her exasperated astonishment, when he makes it, is very funny, without being in any way cruel. I laughed aloud.

Dr Dulcamara (Essex-born baritone Ashley Mercer) makes a dramatic entrance and begins his spiel, producing all manner of ‘wonders’ from his capacious bag and offering, at a one-time-only knock-down price, his miracle wonder cure for all ailments.

The chorus is impressed. Matron Adina is not. The rehearsal ends with their mini-confrontation.

Eloise calls the singers together and gives them notes, about movement, stage business and psychology. The chorus are to remain still and rapt as Matron Adina sings her aria. She is most definitely in charge, but she is also their healer, so they are both overawed and grateful. Belcore is too static, holding his rose for Adina and should make more of his preparation. The relationship between Adina and Dulcamara needs more definition.

Eloise calls the singers together and gives them notes, about movement, stage business and psychology. The chorus are to remain still and rapt as Matron Adina sings her aria. She is most definitely in charge, but she is also their healer, so they are both overawed and grateful. Belcore is too static, holding his rose for Adina and should make more of his preparation. The relationship between Adina and Dulcamara needs more definition.

Through-out Adrian insists that the singers keep tempo and, occasionally, gives notes of his own, mainly to the chorus.

In the lunch break I meet a few more of the chorus members’ characters; there’s Charles, a professional military man wounded in the war, hitching up his trousers when he sits – ramrod straight despite his damaged leg – to avoid stretching their fabric. Luigi, an Italian wounded in the Great War fighting Britain, who came to Clapham following the Londoner nurse who tended him and who is now a stalwart member of the community. He sells newspapers just outside the hospital.

Then it’s back to the South London Hospital to take it ‘from the top’ again.

Tuesday 10th June

It’s an evening rehearsal at St Paul’s and low sun shines in through windows on the opposite side of the church. Eloise makes tea and Adrian is at the piano, as two soloists, Latvian tenor Martins Smaukstelis (Nemorino) and Ashley Mercer (Dr Dulcamara) arrive. They will concentrate on their duet scene in Act One, in which the crafty doctor sells the naïve Nemorino his ‘elixir of love’.

There is a sing through first and male voices echo around the church. Then a quick discussion with Adrian.

There is a sing through first and male voices echo around the church. Then a quick discussion with Adrian.

‘Shall we?’ says Eloise.

The soloists take up positions.

Nemorino approaches Dulcamara with a mixture of desperate hope, excitement and fear. Can this ‘alchemist’ help him win Adina? Dulcamara cannot believe his luck and quickly rips a label from a bottle of red wine, offering it as the famed elixir for all the money in Nemorino’s pockets. The doctor rolls his eyes at the audience, who are complicit in his ruse. Then he wants to get away before his victim twigs, but Nemorino calls him back. How does he use the elixir?

There follows a very funny scene in which the doctor instructs Nemorino in how to open a bottle of wine. This scene is, as Eloise says, ‘all about the bench’, where the two characters sit and most of their interaction happens.

As I watch another kind of alchemy takes place.

Eloise offers suggestions but allows her soloists room to create. These two are almost affectionate, she suggests, they like each other. The doctor invites Nemorino to sit, his gestures and instructions become fatherly in tone. Nemorino is trusting, child-like. The action emerges, through physical gesture as much as song, the singers acting and interacting spontaneously.

Nemorino’s tigerish enthusiasm bubbles over and he starts to rush away, to share his good fortune. Dulcamara realises that if other learn of this, the game will be up, his trickery exposed, so he calls Nemorino back to persuade him to keep the elixir secret. The scene ends in more subdued fashion, as Nemorino is, as Eloise says ‘looking inward’. The tone changes.

We run through again, this time in full voice. Stage action now fits seamlessly to the music – when Nemorino plucks up courage to approach Dulcamara there is what Eloise describes as ‘walking music’ and that’s exactly what it sounds like. The handshake between the two men comes at the climax of a passage of music, carrying over to signal in sound what Dulcamara signals physically – that he cannot extricate his hand from Nemorino’s grateful grasp.

Doubtless there will be refinement, but a scene, musically and emotionally consistent, dramatic and very funny, has come into being where none existed before.

This is alchemy indeed.

Tuesday 17th June

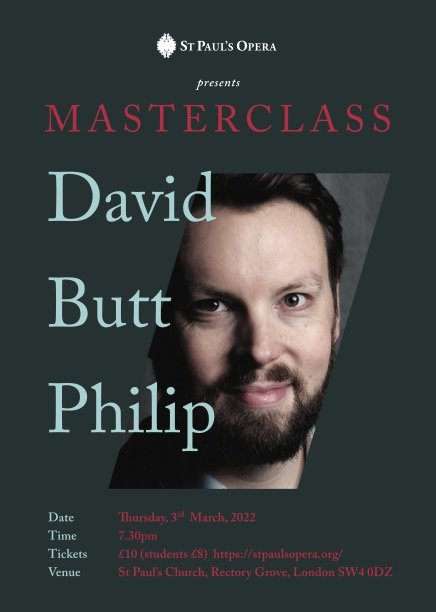

The church is bathed in soft evening light and the whole of the cast is here. So is David Butt Phillip, international opera star and patron of St Paul’s Opera, so the church pews are dotted with a select audience, the VIP Friends of SPO. This is the first time David has seen this developing production. Adrian is at the piano and Eloise is in her customary place.

audience, the VIP Friends of SPO. This is the first time David has seen this developing production. Adrian is at the piano and Eloise is in her customary place.

The singers, especially the soloists, are on their mettle in David’s presence and one or two show signs of nervousness. Plus, Eloise will be focusing more on the soloists this evening, she explains, so as to reinforce the emotional story-telling throughout.

We go from Adina’s first aria in Act One. David reminds the chorus that their staccato phrases towards the end of Adina’s aria should be crisp and succinct beneath the rich and soaring soprano voice, ‘half as long and half as loud’. We repeat and transition into Belcore’s ‘proposal’ aria. There is business here for Nemorino, overhearing Belcore’s declaration of love and reacting to the proposal to his beloved Adina. As Eloise and Martins consider some repositioning, David advises Ted on his stance which should be ‘less  elegant, more military, butch, showing Belcore believes that he’s ready for anything’.

elegant, more military, butch, showing Belcore believes that he’s ready for anything’.

We go again. This time Belcore’s marshalling of his ‘troop’ is more militarily done and obviously for Adina’s benefit. The chorus exits in single file, marching. David advises that, without a conductor to cue them, they have to take responsibility for getting on top of the music, thinking about what’s to come several bars in advance and attacking it ‘on point’. Otherwise the sound will be ‘mushy’.

The first duet between the romantic leads follows, but this isn’t a standard lovers’ duet, it is more complex. Eloise wants clarity of emotional story-telling and so, in the break, she discusses the duet, almost line by line with the two singers, asking each, like a therapist, to describe the feelings of their characters at that point in the aria. So, when we begin again we have flirting, devotion, apparent rejection and pleasure in each other.

And on to Dr Dulcamara’s entrance…

30th June 2025

It is the hottest day of the year so far and the interior of the church feels mercifully cool after the hard sun outside. There are quite a few folk around – a professional photographer, the light and sound technicians, various people unknown to me (donors, critics?) as well as the cast and the musicians.

It is the hottest day of the year so far and the interior of the church feels mercifully cool after the hard sun outside. There are quite a few folk around – a professional photographer, the light and sound technicians, various people unknown to me (donors, critics?) as well as the cast and the musicians.

The stage is, literally, set. It is multi-level in three main blocks and with lots of entrances and exits, perfect for lots of motion in a comedic piece. The red brick walls of the South London Hospital are to the fore, there is a hospital bed, screens, trolley and other ward paraphernalia. On the stage is an old-fashioned, wooden box TV with doors; to either side of the stage are flatscreens to carry surtitles. Strings of lights are hung across the church, they will be illuminated later as darkness falls.

Nurses in 1940/50s uniforms mingle with patients in pyjamas or nightdresses. Ashley (Dr Dulcamara) and Fiona (Adina) wait until the last minute to don their costumes, which are heavy in the heat – especially Dulcamara’s tight fitting leather aviator hat. Musicians arrive one by one and Adrian sits them in their places and begins to talk about the music, while using a bright fan as if to the manner born (he hails from the Basque country, so he probably was). The church begins to feel hotter.

Eloise is everywhere; she’s up in the balcony, checking the sightlines, on stage with Ted (Belcore) discussing how he will enlist Nemorino (by using his own medical chart) and with the cast in the Green Room.

Eloise is everywhere; she’s up in the balcony, checking the sightlines, on stage with Ted (Belcore) discussing how he will enlist Nemorino (by using his own medical chart) and with the cast in the Green Room.

The musicians are all here, so… we begin!

I have heard much of this many times before, but it seems fresh and different now. This is the added element which costumes and staging bring. They also add physical authority to the concept of setting the opera in a post-war Clapham hospital. I knew it would work, but now it seems inspired.

The Adina-Nemorino dynamic is immediate and very strong, as befits the central relationship of the story. The nurses chat and inter-react like workmates. The south Londoners add variety and colour (as well as sound). Music and voices reverberate around the church (it will be interesting to see what sort of impact a full audience will have on the sound).

The spirit of the piece is celebratory and there is a slight carnival aspect, even though it is set in a hospital. It is funny and moving and beautiful. I feel so privileged to have watched this production develop, to talk with the director and soloists and chorus members at various stages. Thank you, all of you.

L’Elisir d’Amore is going to be an enormous success.

N.B. Since this diary was written the St Paul’s Opera Summer production of L’Elisir d’Amore has been given an Assessors Award from the Offie’s which celebrate independent and fringe theatre. Watch this space for a Nomination!

This year saw a unique collaboration for me, with St Paul’s Opera Company, on their production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore (The Elixir of Love). The Director, Eloise Lally, wanted to set her version of the opera in a hospital immediately post-World War two and Patricia Ninian, SPO founder and Director had read my books The Midnight Man and A Death in the Afternoon, which are set in the South London Hospital for Women and Children. So Tricia approached me to see if using that setting might work. I was sure it would.

This year saw a unique collaboration for me, with St Paul’s Opera Company, on their production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore (The Elixir of Love). The Director, Eloise Lally, wanted to set her version of the opera in a hospital immediately post-World War two and Patricia Ninian, SPO founder and Director had read my books The Midnight Man and A Death in the Afternoon, which are set in the South London Hospital for Women and Children. So Tricia approached me to see if using that setting might work. I was sure it would. in time when men were returning home from the war to take up the jobs and roles they had left behind, which had, in their absence, been done by women. Not all the women, especially the younger ones, wanted to return to a purely domestic sphere, but they had little choice. At the South London, however, the opposite was happening. Male medics and staff were leaving, to be replaced by women and male patients were also being excluded. This unique point of tension informed my books and would inform the opera.

in time when men were returning home from the war to take up the jobs and roles they had left behind, which had, in their absence, been done by women. Not all the women, especially the younger ones, wanted to return to a purely domestic sphere, but they had little choice. At the South London, however, the opposite was happening. Male medics and staff were leaving, to be replaced by women and male patients were also being excluded. This unique point of tension informed my books and would inform the opera. small exhibition about the South London, using documents and memorabilia lent to us by Dr Juliet Boyd, former anaesthetist at the hospital and its unofficial archivist. This included everything from an annual report from 1917, showing the medical officers in post (all female – the only male name is that of a chaplain) to protest badges against the closure of the hospital almost seventy years later. The banners (right, with SPO Director, Patricia Ninian) produced by the opera company would be used as information at each of the performances.

small exhibition about the South London, using documents and memorabilia lent to us by Dr Juliet Boyd, former anaesthetist at the hospital and its unofficial archivist. This included everything from an annual report from 1917, showing the medical officers in post (all female – the only male name is that of a chaplain) to protest badges against the closure of the hospital almost seventy years later. The banners (right, with SPO Director, Patricia Ninian) produced by the opera company would be used as information at each of the performances.

I have just returned to a cold and sleety Clapham after the sunnier skies of southern Spain, where the scent of orange blossom was already in the air and the 27th edition of the

I have just returned to a cold and sleety Clapham after the sunnier skies of southern Spain, where the scent of orange blossom was already in the air and the 27th edition of the  castanets dancing to black clad male guitarists, although you could see that if that was what you wanted. No, something fascinating has been happening for a number of years at this festival and this edition was no exception. Younger practitioners are examining the boundaries of what flamenco means, exploring and expanding their art.

castanets dancing to black clad male guitarists, although you could see that if that was what you wanted. No, something fascinating has been happening for a number of years at this festival and this edition was no exception. Younger practitioners are examining the boundaries of what flamenco means, exploring and expanding their art. We did see an amazing reflection on life and death in Finitud, the aforementioned Calero Caballero collaboration. We saw the pair ten years ago when their skill and artistry was expressed beautifully through the traditional forms and we’ve looked out for them ever since. Boy, have they developed. The show included an electric base guitar as well as flamenco guitar and, astonishingly, Mozart’s Requiem. A singer, a dancer and two musicians conjured up the vibrancy of the south American Day of the Dead, the solitude of graveyard contemplation and a lot in between. We had a fun 1930s cartoon of skeletons dancing to make us laugh and ended with an auto de fe. Stunning! This show was hugely emotionally engaging and created some stupendous images which will fill my mind for quite some time. It encapsulates what a new generation of flamenco artists are doing, developing themselves and their art.

We did see an amazing reflection on life and death in Finitud, the aforementioned Calero Caballero collaboration. We saw the pair ten years ago when their skill and artistry was expressed beautifully through the traditional forms and we’ve looked out for them ever since. Boy, have they developed. The show included an electric base guitar as well as flamenco guitar and, astonishingly, Mozart’s Requiem. A singer, a dancer and two musicians conjured up the vibrancy of the south American Day of the Dead, the solitude of graveyard contemplation and a lot in between. We had a fun 1930s cartoon of skeletons dancing to make us laugh and ended with an auto de fe. Stunning! This show was hugely emotionally engaging and created some stupendous images which will fill my mind for quite some time. It encapsulates what a new generation of flamenco artists are doing, developing themselves and their art. in art or, as a writer, on the page? What is creativity? I, for one, will be reflecting on this, with friend and fellow writer, Sunday Times best-selling novelist,

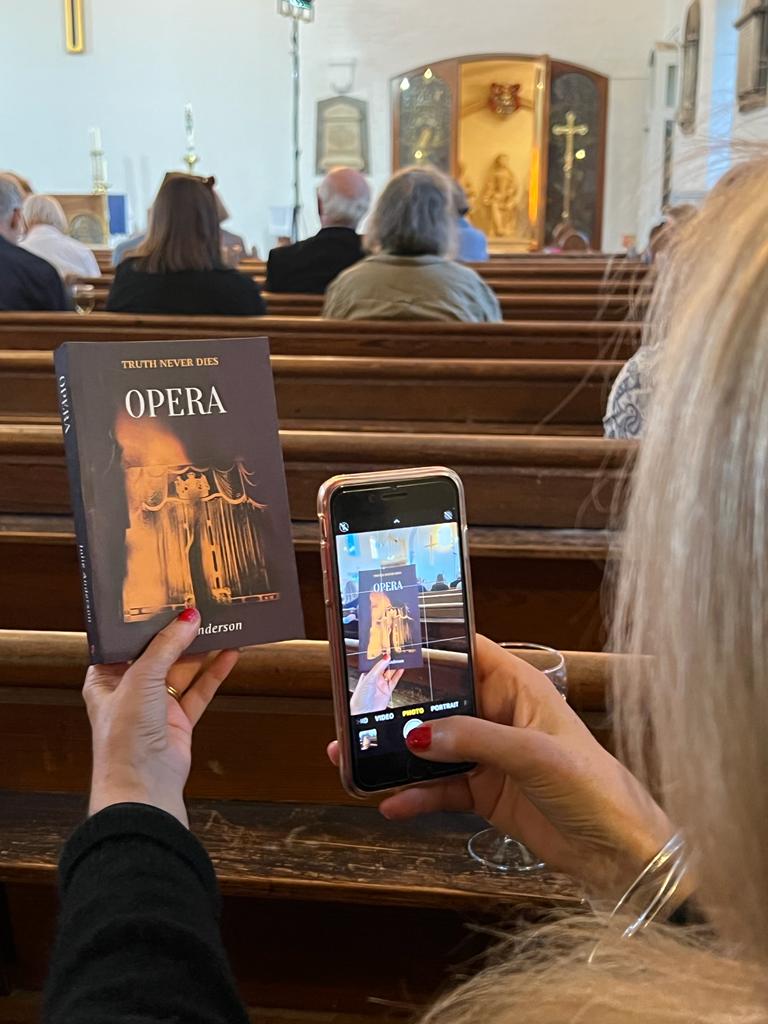

in art or, as a writer, on the page? What is creativity? I, for one, will be reflecting on this, with friend and fellow writer, Sunday Times best-selling novelist,  The low, autumnal sunlight slanted across the churchyard of St Paul’s Church in Clapham on a beautiful September evening one week ago. Cars drew up to the church’s railings, people walked down the winding path to the heavy church doors and inside there was a buzz of anticipation of good entertainment to come. They were there to celebrate the launch of ‘Opera‘ the third in the Cassandra Fortune series of murder mysteries, together with the music of Puccini and Tosca in particular (the opera in ‘Opera‘). I was at the door to greet them.

The low, autumnal sunlight slanted across the churchyard of St Paul’s Church in Clapham on a beautiful September evening one week ago. Cars drew up to the church’s railings, people walked down the winding path to the heavy church doors and inside there was a buzz of anticipation of good entertainment to come. They were there to celebrate the launch of ‘Opera‘ the third in the Cassandra Fortune series of murder mysteries, together with the music of Puccini and Tosca in particular (the opera in ‘Opera‘). I was at the door to greet them. evening’s entertainment), the sound system was set up, the bar was stocked, staffed and ready to dispense and the Claret Press table was ready with signed books for sale. Programmes were handed out at the door. The church filled, gradually, with local friends, of the author or of the opera company, and with those from farther afield who had come to help celebrate. About a third of the crowd were probably also writers, many of them writers of crime fiction (see Anne Coates, author of the Hannah Weybridge mysteries, with Katie Isbester of Claret Press and myself, right). Other Claret authors, Steve Sheppard and Sylvia Vetta were there as well as reknown Clapham authors like Elizabeth Buchan. Clapham Book Festival friends were out in force, as were the members of the Clapham Writers Circle. In total there were between seventy and eight people in the beautiful church.

evening’s entertainment), the sound system was set up, the bar was stocked, staffed and ready to dispense and the Claret Press table was ready with signed books for sale. Programmes were handed out at the door. The church filled, gradually, with local friends, of the author or of the opera company, and with those from farther afield who had come to help celebrate. About a third of the crowd were probably also writers, many of them writers of crime fiction (see Anne Coates, author of the Hannah Weybridge mysteries, with Katie Isbester of Claret Press and myself, right). Other Claret authors, Steve Sheppard and Sylvia Vetta were there as well as reknown Clapham authors like Elizabeth Buchan. Clapham Book Festival friends were out in force, as were the members of the Clapham Writers Circle. In total there were between seventy and eight people in the beautiful church.

Grand opera is always intense and these two arias especially so, so a lightening of the mood was required before the interval. This was provided by an ‘interruption’ by a police constable, PC Willis, who had just arrived from the Houses of Parliament (although dressed in pink). Bass baritone Masimba Ushe delivered the sentry’s song from Gilbert & Sullivan’s Iolanthe ‘When all night long, a chap remains…’ in sonorous and amusing fashion. Laughter heralded the interval, when everyone headed to the bar (where the barkeepers were kept very busy).

Grand opera is always intense and these two arias especially so, so a lightening of the mood was required before the interval. This was provided by an ‘interruption’ by a police constable, PC Willis, who had just arrived from the Houses of Parliament (although dressed in pink). Bass baritone Masimba Ushe delivered the sentry’s song from Gilbert & Sullivan’s Iolanthe ‘When all night long, a chap remains…’ in sonorous and amusing fashion. Laughter heralded the interval, when everyone headed to the bar (where the barkeepers were kept very busy). beforehand and I kept my answers short (as she had told me to, I tend to ramble). People seemed to enjoy it and, after questions from the floor, we ended to loud applause.

beforehand and I kept my answers short (as she had told me to, I tend to ramble). People seemed to enjoy it and, after questions from the floor, we ended to loud applause. bunting made of the posters and other images of Tosca which I had been collecting for months before the book was published.

bunting made of the posters and other images of Tosca which I had been collecting for months before the book was published. Ninian and the singers of St Paul’s Opera, which made it unique. Many of those who attended spoke or wrote to me, telling me how much they enjoyed it. Plus, my publisher sold lots of my books. It was a spectacular way to launch a title and a very special occasion.

Ninian and the singers of St Paul’s Opera, which made it unique. Many of those who attended spoke or wrote to me, telling me how much they enjoyed it. Plus, my publisher sold lots of my books. It was a spectacular way to launch a title and a very special occasion. In April of this year I posted a piece about images of Tosca ( see ‘

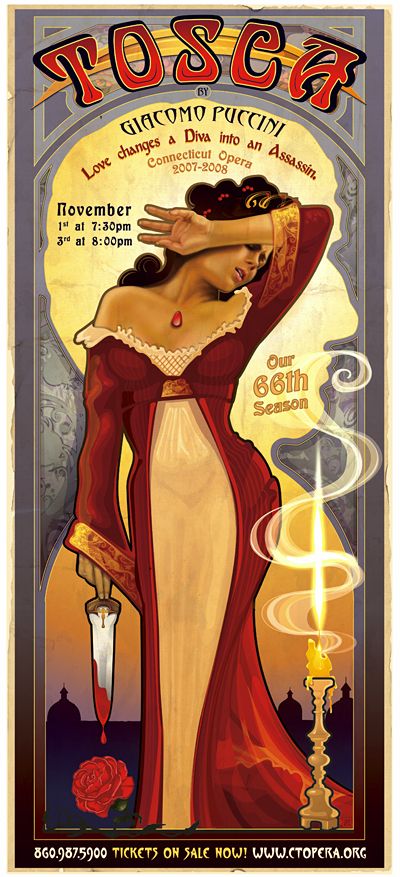

In April of this year I posted a piece about images of Tosca ( see ‘ The artist most associated with Tosca, partly because he designed many posters for the Comedie Francais, where Bernhardt performed, and partly because his style is such a good example of Art Nouveau is probably Alphonse Mucha. Even the Hohenstein poster for the opera’s premiere in Rome in 1900 owed much to Mucha’s style. But his is not the only style which was copied and often other artist’s works were rifled for use on the posters. See the use of the Gustav Klimt’s ‘Judith’ in the poster for Middlebury Opera’s production (right) .

The artist most associated with Tosca, partly because he designed many posters for the Comedie Francais, where Bernhardt performed, and partly because his style is such a good example of Art Nouveau is probably Alphonse Mucha. Even the Hohenstein poster for the opera’s premiere in Rome in 1900 owed much to Mucha’s style. But his is not the only style which was copied and often other artist’s works were rifled for use on the posters. See the use of the Gustav Klimt’s ‘Judith’ in the poster for Middlebury Opera’s production (right) . I found a very striking poster from Poland, probably for a production by the opera company of the city of Bydgoszcz which was very reminiscent of the style of Frieda Kahlo (see left). It drew many comments on social media and divided people, they either loved or hated it.

I found a very striking poster from Poland, probably for a production by the opera company of the city of Bydgoszcz which was very reminiscent of the style of Frieda Kahlo (see left). It drew many comments on social media and divided people, they either loved or hated it. colour in the poster. I’m not sure if this was a sneaky subliminal message, but it is certainly surreal and I do not pretend to understand it, though it seems to be trying for an analysis of the opera at a subconscious level – Tosca pulling Cavaradossi’s strings.

colour in the poster. I’m not sure if this was a sneaky subliminal message, but it is certainly surreal and I do not pretend to understand it, though it seems to be trying for an analysis of the opera at a subconscious level – Tosca pulling Cavaradossi’s strings. life, so there are plenty of leering Scarpias and retreating, suffering Toscas, though often clutching a dagger. The Italian ones are even more lurid than the Hollywood ones ( I suspect because Hollywood treated it as ‘high art’ ), but here is a more restrained offering – ‘The tragic love of Floria Tosca and Mario Cavaradossi commemorated in the immortal melodies of G. Puccini’. The director, ‘Carlo Koch’ is actually the noted German art historian and film director, Karl Koch, who undertook the film in 1939, jointly with Jean Renoir, at Mussolini’s invitation. Koch was Renoir’s assistant on Le Regle de Jeu

life, so there are plenty of leering Scarpias and retreating, suffering Toscas, though often clutching a dagger. The Italian ones are even more lurid than the Hollywood ones ( I suspect because Hollywood treated it as ‘high art’ ), but here is a more restrained offering – ‘The tragic love of Floria Tosca and Mario Cavaradossi commemorated in the immortal melodies of G. Puccini’. The director, ‘Carlo Koch’ is actually the noted German art historian and film director, Karl Koch, who undertook the film in 1939, jointly with Jean Renoir, at Mussolini’s invitation. Koch was Renoir’s assistant on Le Regle de Jeu and Renoir was instrumental in getting Koch out of Germany in 1936. Renoir eventually withdrew from the film, but Koch completed it, together with his assistant, one Luchino Visconti. Incidentally Koch and his wife settled in Barnet, north London once the war ended.

and Renoir was instrumental in getting Koch out of Germany in 1936. Renoir eventually withdrew from the film, but Koch completed it, together with his assistant, one Luchino Visconti. Incidentally Koch and his wife settled in Barnet, north London once the war ended. I know that there is always music to be found in Jerez de la Frontera. Usually it’s of the flamenco variety, but I have, in the past, happened across 13th century song cycles, jazz, classical, modern tribute bands (hearing ‘Radio Gaga’ resounding from the walls of the ancient Alcazar some years ago was quite something) and world music. This summer is no exception with a range of concerts, sometimes free, sometimes charged for, in some spectacular locations. July saw ‘Baile’ a series of flamenco dance performances in the 13th century Claustros de Santo Domingo and ‘Mima’ or Musicas Improvisadas En El Museo Arquelogico in the eponymous museum. I caught the wonderful jazz trio Nocturno on a sultry Wednesday night playing their own compositions, inspired by the night and Frankenstein. The music was stupendous. I wondered what Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley would have made

I know that there is always music to be found in Jerez de la Frontera. Usually it’s of the flamenco variety, but I have, in the past, happened across 13th century song cycles, jazz, classical, modern tribute bands (hearing ‘Radio Gaga’ resounding from the walls of the ancient Alcazar some years ago was quite something) and world music. This summer is no exception with a range of concerts, sometimes free, sometimes charged for, in some spectacular locations. July saw ‘Baile’ a series of flamenco dance performances in the 13th century Claustros de Santo Domingo and ‘Mima’ or Musicas Improvisadas En El Museo Arquelogico in the eponymous museum. I caught the wonderful jazz trio Nocturno on a sultry Wednesday night playing their own compositions, inspired by the night and Frankenstein. The music was stupendous. I wondered what Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley would have made of it, I’d like to think that, free thinker as she was, she would have enjoyed it as much as the audience did. Afterwards, given the temperature, musicians and audience spent the next hour or so in the Plaza Mercado (the old Moorish market place, which features in my novel Reconquista ) drinking excellent wine.

of it, I’d like to think that, free thinker as she was, she would have enjoyed it as much as the audience did. Afterwards, given the temperature, musicians and audience spent the next hour or so in the Plaza Mercado (the old Moorish market place, which features in my novel Reconquista ) drinking excellent wine. part-flamenco-part-arabian (you could say the first comes from the second anyway), modern rock-style electric guitar and the wonderfully fluid arpeggios of the kora. These concerts run into the 55th Fiesta de la Buleria de Jerez, a stunning series of gala concerts with the cream of flamenco performers – Manuel Lignan, Gema Moneo, David Carpio, Antonio El Pipa, Manuela Carrasco and more. The buleria was invented in Jerez, it is very rapid and complex, with demanding changes in rhythm for all performers. Guitarists consider it possibly the most virtuosic of the soleas. Lively and intense, it is also great fun, often performed at parties and as a dance at the end of a show, when all the performers (not just the dancers) join in. With origins in the nineteenth century it was popularised outside of Jerez and other corners of Andalucia in the twentieth century by ‘cross-over’ artists like the guitarist Paco de Lucia and singer Camaron. Still going strong, it is celebrated annually in Jerez, just before the beginning of the vendimia, the wine harvest. This, and the other series of concerts have been augmented by free concerts and dance performances in Plaza Ascuncion, in front of the 13th century church of San Dionysio and the neo-classical town hall.

part-flamenco-part-arabian (you could say the first comes from the second anyway), modern rock-style electric guitar and the wonderfully fluid arpeggios of the kora. These concerts run into the 55th Fiesta de la Buleria de Jerez, a stunning series of gala concerts with the cream of flamenco performers – Manuel Lignan, Gema Moneo, David Carpio, Antonio El Pipa, Manuela Carrasco and more. The buleria was invented in Jerez, it is very rapid and complex, with demanding changes in rhythm for all performers. Guitarists consider it possibly the most virtuosic of the soleas. Lively and intense, it is also great fun, often performed at parties and as a dance at the end of a show, when all the performers (not just the dancers) join in. With origins in the nineteenth century it was popularised outside of Jerez and other corners of Andalucia in the twentieth century by ‘cross-over’ artists like the guitarist Paco de Lucia and singer Camaron. Still going strong, it is celebrated annually in Jerez, just before the beginning of the vendimia, the wine harvest. This, and the other series of concerts have been augmented by free concerts and dance performances in Plaza Ascuncion, in front of the 13th century church of San Dionysio and the neo-classical town hall. the May Queen. But there’s not a virtuous maid to be found. Shock, horror! Too many have erred ( being seen ‘out after dusk’, or ‘wearing short skirts’ ). So a King of the May is preferred, the virtuous (and virginal) Albert Herring.

the May Queen. But there’s not a virtuous maid to be found. Shock, horror! Too many have erred ( being seen ‘out after dusk’, or ‘wearing short skirts’ ). So a King of the May is preferred, the virtuous (and virginal) Albert Herring. We filed inside, carrying cushions ( those pews can be unforgiving to the rear end ) to find the colour scheme continued. The musical director and conductor, Panaretos Kyriadzidis took up his position, with pianist Francesca Lauri and the story began. Florence Pike (mezzo, Natasha Elliott), housekeeper to Lady Billows (soprano, Charlotte Brosnan) was preparing milady’s parlour for the meeting of the May Day committee – Miss Wordsworth (soprano, Anna Marmion), mayor Mr Gedge (baritone, Adam Brown), vicar Upfold (tenor, Peder Holterman) and Superintendent Budd (bass, Masimba Ushe) to choose the May Queen.

We filed inside, carrying cushions ( those pews can be unforgiving to the rear end ) to find the colour scheme continued. The musical director and conductor, Panaretos Kyriadzidis took up his position, with pianist Francesca Lauri and the story began. Florence Pike (mezzo, Natasha Elliott), housekeeper to Lady Billows (soprano, Charlotte Brosnan) was preparing milady’s parlour for the meeting of the May Day committee – Miss Wordsworth (soprano, Anna Marmion), mayor Mr Gedge (baritone, Adam Brown), vicar Upfold (tenor, Peder Holterman) and Superintendent Budd (bass, Masimba Ushe) to choose the May Queen. sensible, if ponderous and all defer to milady, who is ‘overbearingly enthusiastic’ (as described by Britten and his librettist, Eric Crozier). Yet Albert (tenor, Hugh Benson) is decided not upper class, being the greengrocer’s son and neither are his friends, Sid, the butcher’s boy (baritone, Alfred Mitchell) and Nancy, his girlfriend (mezzo, Megan Baker). One of the delights of this opera is the demotic, everyday language which Britten insisted upon. It is used well and wittily – after his night of debauchery which the May King prize money affords him, Albert thanks the shocked villagers ‘And I’d like to thank you all, for giving me the wherewithal.’

sensible, if ponderous and all defer to milady, who is ‘overbearingly enthusiastic’ (as described by Britten and his librettist, Eric Crozier). Yet Albert (tenor, Hugh Benson) is decided not upper class, being the greengrocer’s son and neither are his friends, Sid, the butcher’s boy (baritone, Alfred Mitchell) and Nancy, his girlfriend (mezzo, Megan Baker). One of the delights of this opera is the demotic, everyday language which Britten insisted upon. It is used well and wittily – after his night of debauchery which the May King prize money affords him, Albert thanks the shocked villagers ‘And I’d like to thank you all, for giving me the wherewithal.’ The opera is funny and this production is full of energy, verve and wit. The audience become participants, urged, at specific moments to rise for Lady Billows (as if in church) or to applaud. There are ‘Missing Person’ handbills circulated and beach balls thrown. Throughout, however, the music is spikily superb. Another great success for St Paul’s Opera and a triumphant excursion outside their usual repertoire. The auditorium was almost full last night and the next two night’s are sold out completely.

The opera is funny and this production is full of energy, verve and wit. The audience become participants, urged, at specific moments to rise for Lady Billows (as if in church) or to applaud. There are ‘Missing Person’ handbills circulated and beach balls thrown. Throughout, however, the music is spikily superb. Another great success for St Paul’s Opera and a triumphant excursion outside their usual repertoire. The auditorium was almost full last night and the next two night’s are sold out completely. … but rather Albert Herring, by Benjamin Britten. This year’s Summer Opera from St Paul’s Opera Company, Clapham. Last night was the ‘Insight’ evening, designed to introduce the opera to those who may not know it and to stimulate discussion among those who did. I learned a lot.

… but rather Albert Herring, by Benjamin Britten. This year’s Summer Opera from St Paul’s Opera Company, Clapham. Last night was the ‘Insight’ evening, designed to introduce the opera to those who may not know it and to stimulate discussion among those who did. I learned a lot. serious piece The Rape of Lucretia. Albert Herring a chamber opera in three acts, was the result.

serious piece The Rape of Lucretia. Albert Herring a chamber opera in three acts, was the result. The following morning, with Albert missing, the villagers discover his May crown in the well and everyone is thrown into mourning. In its midst Albert turns up, rather the worse for wear and thanks the village committee for funding his night of pleasure. All are, needless to say, outraged, but Albert carries it off, standing up to his mother in the process. The opera was an immediate success, receiving performances in the U.S., Copenhagen, Oslo and Moscow. It has since been performed all over the world.

The following morning, with Albert missing, the villagers discover his May crown in the well and everyone is thrown into mourning. In its midst Albert turns up, rather the worse for wear and thanks the village committee for funding his night of pleasure. All are, needless to say, outraged, but Albert carries it off, standing up to his mother in the process. The opera was an immediate success, receiving performances in the U.S., Copenhagen, Oslo and Moscow. It has since been performed all over the world. Wintle, Panaretos Kyriatzidis (musical director of St Paul’s Opera) and Annemiek van Elst (Director of Albert Herring) facilitated by Jonathan Boardman. The evening closed with questions from the audience (which could have gone on for far longer ). Sadly, dusk had well and truly fallen and the evening drew to a close.

Wintle, Panaretos Kyriatzidis (musical director of St Paul’s Opera) and Annemiek van Elst (Director of Albert Herring) facilitated by Jonathan Boardman. The evening closed with questions from the audience (which could have gone on for far longer ). Sadly, dusk had well and truly fallen and the evening drew to a close. connected with it.

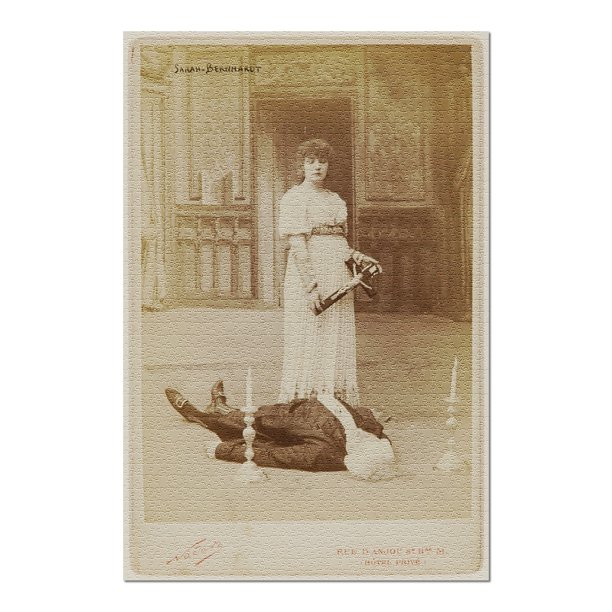

connected with it. Puccini’s opera was based. The first performance of the opera was in 1900 in Rome and the poster was by Adolfo Hohenstein who also designed the stage sets. It is very much in the Art Noveau style of Mucha and features the same scene as the Bernhardt postcard, a scene which was to feature again and again in images of the opera. The pious Tosca sets candles at the head of the Baron, whom she has just killed ( in self-defence, as he has just tried to rape her ) and places a crucifix on his chest.

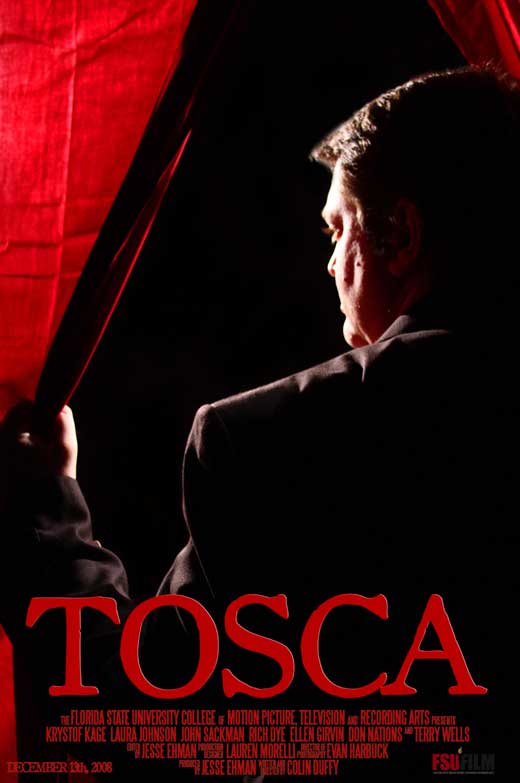

Puccini’s opera was based. The first performance of the opera was in 1900 in Rome and the poster was by Adolfo Hohenstein who also designed the stage sets. It is very much in the Art Noveau style of Mucha and features the same scene as the Bernhardt postcard, a scene which was to feature again and again in images of the opera. The pious Tosca sets candles at the head of the Baron, whom she has just killed ( in self-defence, as he has just tried to rape her ) and places a crucifix on his chest. Many of the more modern images are explicit about the subject matter and the link the opera makes between sex and death (see left). The dagger is a recurring motif, as is blood – red is the most popular colour. The Castel Sant’Angelo appears too. Tosca herself, as in Bernhardt’s time, is often the the central image, although other posters prefer to concentrate on Scarpia, like that for Florida State Opera (right). Only a few depict Cavaradossi, the hero. Ordinarily one might say that this is an example of

Many of the more modern images are explicit about the subject matter and the link the opera makes between sex and death (see left). The dagger is a recurring motif, as is blood – red is the most popular colour. The Castel Sant’Angelo appears too. Tosca herself, as in Bernhardt’s time, is often the the central image, although other posters prefer to concentrate on Scarpia, like that for Florida State Opera (right). Only a few depict Cavaradossi, the hero. Ordinarily one might say that this is an example of  ‘the devil has all the best tunes’, except that in the opera itself, it is the tenor arias, belonging to Cavaradossi, which are most memorable.

‘the devil has all the best tunes’, except that in the opera itself, it is the tenor arias, belonging to Cavaradossi, which are most memorable. In particular the language we use when we talk about singing.

In particular the language we use when we talk about singing. to the crescendo, was described as the ‘luxury version’. ‘Don’t be polite, don’t apologise for the note’ signified not to sing it lightly, not giving it due sound, but to sing it loudly, the quality of loudness being needed in a theatre. Also, ‘complete the note’, indicated holding it for as long as necessary. Easily understood, though less easy to define.

to the crescendo, was described as the ‘luxury version’. ‘Don’t be polite, don’t apologise for the note’ signified not to sing it lightly, not giving it due sound, but to sing it loudly, the quality of loudness being needed in a theatre. Also, ‘complete the note’, indicated holding it for as long as necessary. Easily understood, though less easy to define. It’s at the Hootananny, 95 Effra Road, Brixton, SW2 1DF and doors open at 7.30 pm on 7th March, where I’ll be appearing alongside William Ryan, Ashley Hickson-Lovence, Leo Moynihan, West Camel, Paul Bassett Davies and Paul Eccentric. It’s free to attend and there’s booze and books on sale. If you’re in south London why not come along?

It’s at the Hootananny, 95 Effra Road, Brixton, SW2 1DF and doors open at 7.30 pm on 7th March, where I’ll be appearing alongside William Ryan, Ashley Hickson-Lovence, Leo Moynihan, West Camel, Paul Bassett Davies and Paul Eccentric. It’s free to attend and there’s booze and books on sale. If you’re in south London why not come along?