‘The Midnight Man’ is published and out in the wild. I’ve had an amazing week following its publication, with some tremendous reviews. My interview with Crime Time presenter Paul Burke was great fun, although recorded earlier (you can listen to it on the link below) and I’m doing more, with UK Crime Book Club on the 17th and Riverside Radio Arts on 24th May. In between there are book  clubs and libraries to visit where I’ll be talking about ‘The Midnight Man’ and the South London Hospital for Women and Children. Tomorrow I’m off to the Royal College of Nursing for the launch of their Summer exhibition and programme of events ‘Shining a Light’.

clubs and libraries to visit where I’ll be talking about ‘The Midnight Man’ and the South London Hospital for Women and Children. Tomorrow I’m off to the Royal College of Nursing for the launch of their Summer exhibition and programme of events ‘Shining a Light’.

The RCN isn’t the only medical institution to be interested, the UK Association for the History of Nursing has asked for a copy and ‘The Midnight Man’ will feature in their journal and possibly on their website. The Fawcett Society has shown an interest and the Historic Novel Society is carrying a review. So lots of interest.

In the meanwhile I’ve been to see ‘Nye’ the new play by Tim Price, based on the life of Aneurin Bevan, ‘founder’ of the National Health Service. Bevan, played by Michael Sheen, was Minister for Health in the Attlee government and the driving force behind the creation of the NHS, although he had to make compromises to force it through. I was pleased to see that the play represented the opposition of the some of the medical unions, something which is also referred to in ‘The Midnight Man’. We treasure the NHS now ( or should do, though I appreciate that many years of underfunding and ‘reorganisations’ has meant long delays and some deficiencies ) but, at the time it wasn’t a foregone conclusion that it would be set up, let alone survive. Yet, as the post curtain call stats shone on to the back of the stage show, it has saved many lives and alleviated much suffering, which

‘founder’ of the National Health Service. Bevan, played by Michael Sheen, was Minister for Health in the Attlee government and the driving force behind the creation of the NHS, although he had to make compromises to force it through. I was pleased to see that the play represented the opposition of the some of the medical unions, something which is also referred to in ‘The Midnight Man’. We treasure the NHS now ( or should do, though I appreciate that many years of underfunding and ‘reorganisations’ has meant long delays and some deficiencies ) but, at the time it wasn’t a foregone conclusion that it would be set up, let alone survive. Yet, as the post curtain call stats shone on to the back of the stage show, it has saved many lives and alleviated much suffering, which  would not have been the case had it not existed.

would not have been the case had it not existed.

The play also seeks to show the pain, anguish and anger caused when medicine is not available, because of the inability to pay for care, something I tried to do in ‘Midnight Man’ through the character of Phoebe. Tuberculosis was a killer disease, for which there was no cure, and which reached pandemic proportions at different times in its history. It was also highly contagious and sufferers were isolated, with their loved ones made to keep a distance from them (not unlike COVID).

I can certainly recommend the play and it is a remarkable performance by Sheen, with Sharon Small as Jennie Lee. It’s not the only recent West End play which features the period immediately post-war. Lucy Kirkwood’s ‘The Human Body’ starring Keeley Hawes and Jack Whitehall was at the Donmar until the end of last month, about post-war female emancipation and the NHS. Must be something in the zeitgeist.

I speak about some of this in the interview with Paul. If you’re interested you can hear that here.

Only three weeks to go before my next book is published (by Hobeck Books) and I’ve received some very complimentary comments from fellow authors who have read proofs, like Vaseem Khan (award-winning author of the Malabar House series, set in 1950s India), Victoria Dowd (award-winning author of the Smart Woman series) and Elizabeth Buchan (multi-award winner and fellow south Londoner ). This is the enjoyable time, the pleasant anticipation, the dream of a best-seller, unsullied by one star reviews or poor sales numbers.

Only three weeks to go before my next book is published (by Hobeck Books) and I’ve received some very complimentary comments from fellow authors who have read proofs, like Vaseem Khan (award-winning author of the Malabar House series, set in 1950s India), Victoria Dowd (award-winning author of the Smart Woman series) and Elizabeth Buchan (multi-award winner and fellow south Londoner ). This is the enjoyable time, the pleasant anticipation, the dream of a best-seller, unsullied by one star reviews or poor sales numbers. so I’ll be speaking at the Clapham Society and local libraries and book clubs. Some are London wide – the London Transport Museum is carrying the book in its shop and I’ll be working with them to be part of their events calendar. Some are national – so I’ll be part of the Royal College of Nursing’s Summer exhibition and events programme, which is taking place across the country. I’m looking forward to attending its launch on 10th May (see above).

so I’ll be speaking at the Clapham Society and local libraries and book clubs. Some are London wide – the London Transport Museum is carrying the book in its shop and I’ll be working with them to be part of their events calendar. Some are national – so I’ll be part of the Royal College of Nursing’s Summer exhibition and events programme, which is taking place across the country. I’m looking forward to attending its launch on 10th May (see above). not a medic, though she worked for the RCN; a third generation involvement with nursing and medicine, albeit in a different capacity to her surgeon great grandmother. She told me lots of stories about Maud, known by the family as ‘Aunt Mary’ and sent me a photograph of her portrait, which currently hangs in Antonia’s mother’s house in London.

not a medic, though she worked for the RCN; a third generation involvement with nursing and medicine, albeit in a different capacity to her surgeon great grandmother. She told me lots of stories about Maud, known by the family as ‘Aunt Mary’ and sent me a photograph of her portrait, which currently hangs in Antonia’s mother’s house in London. I don’t know the answer to that and neither did Antonia. I hope to be able to speak with her father, who has a fund of stories about ‘Aunt Mary’ which might be enlightening. Nonetheless, I like to think that Maud, who had probably developed something of a thick skin by this time – she was denounced from the pulpit by her minister father (he said he would rather she died than became a doctor) when she was younger and had to blaze trails in other ways, decided, rather like Groucho Marx, not to join any club which would have her as a member, especially one which, in years previously, would not admit her.

I don’t know the answer to that and neither did Antonia. I hope to be able to speak with her father, who has a fund of stories about ‘Aunt Mary’ which might be enlightening. Nonetheless, I like to think that Maud, who had probably developed something of a thick skin by this time – she was denounced from the pulpit by her minister father (he said he would rather she died than became a doctor) when she was younger and had to blaze trails in other ways, decided, rather like Groucho Marx, not to join any club which would have her as a member, especially one which, in years previously, would not admit her. This is not the only remarkable coincidence attaching to this book. Early in the writing process, at first draft stage, I received an unanticipated invitation to a birthday celebration for a friend and couldn’t (for reasons too tedious to go into here) buy a birthday gift in time. So my gift was to name a character after my friend in the new book. I duly did so and, just prior to final editing, I sent her a copy of the manuscript. If she hadn’t liked ‘her’ character, or had had second thoughts about my using her name, she could withdraw and I would change the name. She and her partner, who also had a named character, were very happy, though she responded by sending me a copy of the birth certificate of her first born son. He was born at the South London Hospital in the 1970s! She had never mentioned where he was born (he now lives in Canada) so I had no idea. Thus, I found, my friend was a real patient at the real hospital as well as being a ‘character’ in the fictional version. What are the chances of that?

This is not the only remarkable coincidence attaching to this book. Early in the writing process, at first draft stage, I received an unanticipated invitation to a birthday celebration for a friend and couldn’t (for reasons too tedious to go into here) buy a birthday gift in time. So my gift was to name a character after my friend in the new book. I duly did so and, just prior to final editing, I sent her a copy of the manuscript. If she hadn’t liked ‘her’ character, or had had second thoughts about my using her name, she could withdraw and I would change the name. She and her partner, who also had a named character, were very happy, though she responded by sending me a copy of the birth certificate of her first born son. He was born at the South London Hospital in the 1970s! She had never mentioned where he was born (he now lives in Canada) so I had no idea. Thus, I found, my friend was a real patient at the real hospital as well as being a ‘character’ in the fictional version. What are the chances of that? Two happy accidents; I hope they bode well for the book. ‘The Midnight Man’ is published by Hobeck Books on 30th April. I will be posting further pieces about it as the date approaches. Available for pre-order from Mr Besos’

Two happy accidents; I hope they bode well for the book. ‘The Midnight Man’ is published by Hobeck Books on 30th April. I will be posting further pieces about it as the date approaches. Available for pre-order from Mr Besos’  I am very pleased with the cover of my next novel, The Midnight Man. Created by graphic designer,

I am very pleased with the cover of my next novel, The Midnight Man. Created by graphic designer,

hereby hangs another tale, which I will doubtless return to.

hereby hangs another tale, which I will doubtless return to. I have just returned to a cold and sleety Clapham after the sunnier skies of southern Spain, where the scent of orange blossom was already in the air and the 27th edition of the

I have just returned to a cold and sleety Clapham after the sunnier skies of southern Spain, where the scent of orange blossom was already in the air and the 27th edition of the  castanets dancing to black clad male guitarists, although you could see that if that was what you wanted. No, something fascinating has been happening for a number of years at this festival and this edition was no exception. Younger practitioners are examining the boundaries of what flamenco means, exploring and expanding their art.

castanets dancing to black clad male guitarists, although you could see that if that was what you wanted. No, something fascinating has been happening for a number of years at this festival and this edition was no exception. Younger practitioners are examining the boundaries of what flamenco means, exploring and expanding their art. We did see an amazing reflection on life and death in Finitud, the aforementioned Calero Caballero collaboration. We saw the pair ten years ago when their skill and artistry was expressed beautifully through the traditional forms and we’ve looked out for them ever since. Boy, have they developed. The show included an electric base guitar as well as flamenco guitar and, astonishingly, Mozart’s Requiem. A singer, a dancer and two musicians conjured up the vibrancy of the south American Day of the Dead, the solitude of graveyard contemplation and a lot in between. We had a fun 1930s cartoon of skeletons dancing to make us laugh and ended with an auto de fe. Stunning! This show was hugely emotionally engaging and created some stupendous images which will fill my mind for quite some time. It encapsulates what a new generation of flamenco artists are doing, developing themselves and their art.

We did see an amazing reflection on life and death in Finitud, the aforementioned Calero Caballero collaboration. We saw the pair ten years ago when their skill and artistry was expressed beautifully through the traditional forms and we’ve looked out for them ever since. Boy, have they developed. The show included an electric base guitar as well as flamenco guitar and, astonishingly, Mozart’s Requiem. A singer, a dancer and two musicians conjured up the vibrancy of the south American Day of the Dead, the solitude of graveyard contemplation and a lot in between. We had a fun 1930s cartoon of skeletons dancing to make us laugh and ended with an auto de fe. Stunning! This show was hugely emotionally engaging and created some stupendous images which will fill my mind for quite some time. It encapsulates what a new generation of flamenco artists are doing, developing themselves and their art. in art or, as a writer, on the page? What is creativity? I, for one, will be reflecting on this, with friend and fellow writer, Sunday Times best-selling novelist,

in art or, as a writer, on the page? What is creativity? I, for one, will be reflecting on this, with friend and fellow writer, Sunday Times best-selling novelist,

Deep inside the Blavatnik Building, itself recently the subject of a Supreme Court ruling, sit two small ‘rooms’ white painted ‘blocks’ from outside, but full of light, water and reflection within. These are Yayoi’s Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms, global phenomena. Tickets are limited and even when you have them you will queue to enter each room. At four fifteen on a Friday those queues were each about ten minutes in length, but getting longer as time went on. When you get to the doors you are allowed inside in groups of six people only and, when you’re inside, it’s easy to see why numbers are restricted.

Deep inside the Blavatnik Building, itself recently the subject of a Supreme Court ruling, sit two small ‘rooms’ white painted ‘blocks’ from outside, but full of light, water and reflection within. These are Yayoi’s Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms, global phenomena. Tickets are limited and even when you have them you will queue to enter each room. At four fifteen on a Friday those queues were each about ten minutes in length, but getting longer as time went on. When you get to the doors you are allowed inside in groups of six people only and, when you’re inside, it’s easy to see why numbers are restricted.  ). It is disorientating; difficult to tell who is real and who is reflection – and it wasn’t any easier looking at the photos afterwards. The chandelier repeats into an apparently vast chasm in the floor as well as along corridors into space. There are reflections of reflections, not all in the manner you imagine either, but when, say, a pair of bodyless photographing hands gets caught in the regressions.

). It is disorientating; difficult to tell who is real and who is reflection – and it wasn’t any easier looking at the photos afterwards. The chandelier repeats into an apparently vast chasm in the floor as well as along corridors into space. There are reflections of reflections, not all in the manner you imagine either, but when, say, a pair of bodyless photographing hands gets caught in the regressions. A myriad of lights are hung from the ceiling ( at least that’s how I reasoned it must work, I don’t actually know if that’s correct ) reflecting in multiple mirrors again, but also in the water on the floor. The visitor walks along a three foot wide pathway between the lights from one side of the ‘room’ to the other, something which takes but two or three minutes, if one was walking at normal pace. In fact one walks then stands, marvelling at the reflections and the lights, before starting out again. What the photographs in this piece don’t show is the variation in the colours of these lights as they slowly change from colour scheme to colour scheme. That is best shown when you look into the water (see below for a slightly better representation).

A myriad of lights are hung from the ceiling ( at least that’s how I reasoned it must work, I don’t actually know if that’s correct ) reflecting in multiple mirrors again, but also in the water on the floor. The visitor walks along a three foot wide pathway between the lights from one side of the ‘room’ to the other, something which takes but two or three minutes, if one was walking at normal pace. In fact one walks then stands, marvelling at the reflections and the lights, before starting out again. What the photographs in this piece don’t show is the variation in the colours of these lights as they slowly change from colour scheme to colour scheme. That is best shown when you look into the water (see below for a slightly better representation). biographical details which place the rooms into context of Yayoi Kushama’s life and work, plus the wonderful mirror box which in featured in an earlier piece I wrote when the Tate extension first opened. That too is worth seeing and playing with. Booking is currently until April though the exhibition is closed for maintenance in March. At a tenner it’s worth visiting (and you can catch the wonderful standing collection and some superb, free exhibitions, like A Year in Art; Australia 1992, which I’ve also written about elsewhere ). Highly recommended.

biographical details which place the rooms into context of Yayoi Kushama’s life and work, plus the wonderful mirror box which in featured in an earlier piece I wrote when the Tate extension first opened. That too is worth seeing and playing with. Booking is currently until April though the exhibition is closed for maintenance in March. At a tenner it’s worth visiting (and you can catch the wonderful standing collection and some superb, free exhibitions, like A Year in Art; Australia 1992, which I’ve also written about elsewhere ). Highly recommended. In April of this year I posted a piece about images of Tosca ( see ‘

In April of this year I posted a piece about images of Tosca ( see ‘ The artist most associated with Tosca, partly because he designed many posters for the Comedie Francais, where Bernhardt performed, and partly because his style is such a good example of Art Nouveau is probably Alphonse Mucha. Even the Hohenstein poster for the opera’s premiere in Rome in 1900 owed much to Mucha’s style. But his is not the only style which was copied and often other artist’s works were rifled for use on the posters. See the use of the Gustav Klimt’s ‘Judith’ in the poster for Middlebury Opera’s production (right) .

The artist most associated with Tosca, partly because he designed many posters for the Comedie Francais, where Bernhardt performed, and partly because his style is such a good example of Art Nouveau is probably Alphonse Mucha. Even the Hohenstein poster for the opera’s premiere in Rome in 1900 owed much to Mucha’s style. But his is not the only style which was copied and often other artist’s works were rifled for use on the posters. See the use of the Gustav Klimt’s ‘Judith’ in the poster for Middlebury Opera’s production (right) . I found a very striking poster from Poland, probably for a production by the opera company of the city of Bydgoszcz which was very reminiscent of the style of Frieda Kahlo (see left). It drew many comments on social media and divided people, they either loved or hated it.

I found a very striking poster from Poland, probably for a production by the opera company of the city of Bydgoszcz which was very reminiscent of the style of Frieda Kahlo (see left). It drew many comments on social media and divided people, they either loved or hated it. colour in the poster. I’m not sure if this was a sneaky subliminal message, but it is certainly surreal and I do not pretend to understand it, though it seems to be trying for an analysis of the opera at a subconscious level – Tosca pulling Cavaradossi’s strings.

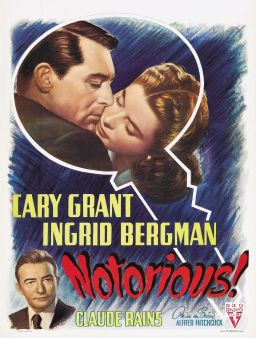

colour in the poster. I’m not sure if this was a sneaky subliminal message, but it is certainly surreal and I do not pretend to understand it, though it seems to be trying for an analysis of the opera at a subconscious level – Tosca pulling Cavaradossi’s strings. life, so there are plenty of leering Scarpias and retreating, suffering Toscas, though often clutching a dagger. The Italian ones are even more lurid than the Hollywood ones ( I suspect because Hollywood treated it as ‘high art’ ), but here is a more restrained offering – ‘The tragic love of Floria Tosca and Mario Cavaradossi commemorated in the immortal melodies of G. Puccini’. The director, ‘Carlo Koch’ is actually the noted German art historian and film director, Karl Koch, who undertook the film in 1939, jointly with Jean Renoir, at Mussolini’s invitation. Koch was Renoir’s assistant on Le Regle de Jeu

life, so there are plenty of leering Scarpias and retreating, suffering Toscas, though often clutching a dagger. The Italian ones are even more lurid than the Hollywood ones ( I suspect because Hollywood treated it as ‘high art’ ), but here is a more restrained offering – ‘The tragic love of Floria Tosca and Mario Cavaradossi commemorated in the immortal melodies of G. Puccini’. The director, ‘Carlo Koch’ is actually the noted German art historian and film director, Karl Koch, who undertook the film in 1939, jointly with Jean Renoir, at Mussolini’s invitation. Koch was Renoir’s assistant on Le Regle de Jeu and Renoir was instrumental in getting Koch out of Germany in 1936. Renoir eventually withdrew from the film, but Koch completed it, together with his assistant, one Luchino Visconti. Incidentally Koch and his wife settled in Barnet, north London once the war ended.

and Renoir was instrumental in getting Koch out of Germany in 1936. Renoir eventually withdrew from the film, but Koch completed it, together with his assistant, one Luchino Visconti. Incidentally Koch and his wife settled in Barnet, north London once the war ended. women through the ages. I went along yesterday and found it informative and interesting. It’s a small exhibition which considers an enduring subject, the presentation of a female likeness looking out of a window, sometimes directly at the viewer, sometimes not. Women have often been represented like this, usually by men, for various purposes, the sacred, the profane, the decorative or the titillating. I was hard pressed to think of more than one or two examples where men were represented in this way.

women through the ages. I went along yesterday and found it informative and interesting. It’s a small exhibition which considers an enduring subject, the presentation of a female likeness looking out of a window, sometimes directly at the viewer, sometimes not. Women have often been represented like this, usually by men, for various purposes, the sacred, the profane, the decorative or the titillating. I was hard pressed to think of more than one or two examples where men were represented in this way. man climbing a ladder to present apples to a woman in a window, probably a hetaira or courtesan. The fun times in the ancient world give way during the medieval period to the discouraging of looking at women, in the window or elsewhere, for fear of arousal and sin. In this period the ‘woman’ is the Madonna (see by Dirk Bouts left) in her role as the ‘window to heaven’, a symbolic window at her back. Or the saint suffering for her faith (a striking and slightly unsettling stone bas relief/sculpture of an incarcerated woman pressing her face against the bars of her cell). Moving on to the Renaissance and non-divine women are the subjects again – I was particularly struck by the Botticelli (his ‘line’ is always mesmerising). Through the Dutch interiors, showing women if not through windows then beside them, playing instruments, reading letters; then to the wonderful Rembrandt of an un-named young woman who leans out of the canvas in all her human glory (see above right).

man climbing a ladder to present apples to a woman in a window, probably a hetaira or courtesan. The fun times in the ancient world give way during the medieval period to the discouraging of looking at women, in the window or elsewhere, for fear of arousal and sin. In this period the ‘woman’ is the Madonna (see by Dirk Bouts left) in her role as the ‘window to heaven’, a symbolic window at her back. Or the saint suffering for her faith (a striking and slightly unsettling stone bas relief/sculpture of an incarcerated woman pressing her face against the bars of her cell). Moving on to the Renaissance and non-divine women are the subjects again – I was particularly struck by the Botticelli (his ‘line’ is always mesmerising). Through the Dutch interiors, showing women if not through windows then beside them, playing instruments, reading letters; then to the wonderful Rembrandt of an un-named young woman who leans out of the canvas in all her human glory (see above right). Degas and a Sickert, but the exhibition didn’t follow a linear timeline, interspersing modern works with the old. Some of these were more successful than others. Some were interesting – the ‘swap’ of poses and locations, between a female photographer and a female prostitute (I cannot remember the name of the photographer, which is annoying). Both women looked very much at home in their new personas.

Degas and a Sickert, but the exhibition didn’t follow a linear timeline, interspersing modern works with the old. Some of these were more successful than others. Some were interesting – the ‘swap’ of poses and locations, between a female photographer and a female prostitute (I cannot remember the name of the photographer, which is annoying). Both women looked very much at home in their new personas. being beckoned forward by a faceless man in a car and rejecting his summons by holding up her palm. This, like the Codrington, with its dead hen and half drunk bottle of what looks like vodka, was a story in a picture, or many possible stories. There were some beautifully staged photographs, the woman reading a letter (an eviction notice, it is mounted in a frame next to the photograph) which echoed those Dutch interiors and a super Australian piece ‘The Apartment’ showing two women in a domestic scene overlooking an industrial harbour – its perspective was remarkable.

being beckoned forward by a faceless man in a car and rejecting his summons by holding up her palm. This, like the Codrington, with its dead hen and half drunk bottle of what looks like vodka, was a story in a picture, or many possible stories. There were some beautifully staged photographs, the woman reading a letter (an eviction notice, it is mounted in a frame next to the photograph) which echoed those Dutch interiors and a super Australian piece ‘The Apartment’ showing two women in a domestic scene overlooking an industrial harbour – its perspective was remarkable. Britain’s Summer exhibition on Walter Sickert (1860 -1942). A pupil of James Macneill Whistler, friend of Edgar Degas and member of the New English Art Club as well as founding member of the Camden Town Group, Sickert seems to have been the most connected of painters. Forster was twenty years younger (1879 – 1970 ) and, similarly, a member of groups, in his case, the Apostles and then the Bloomsbury Group. Forster went on to pre-eminence, rather more than Sickert did, although the visual artist’s influence is felt, as the exhibition demonstrates, on generations of later painters, especially in England.

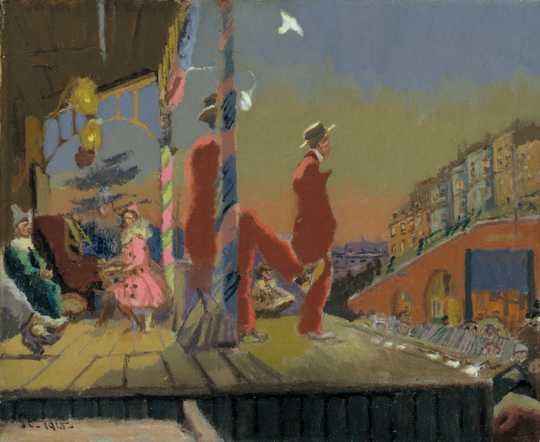

Britain’s Summer exhibition on Walter Sickert (1860 -1942). A pupil of James Macneill Whistler, friend of Edgar Degas and member of the New English Art Club as well as founding member of the Camden Town Group, Sickert seems to have been the most connected of painters. Forster was twenty years younger (1879 – 1970 ) and, similarly, a member of groups, in his case, the Apostles and then the Bloomsbury Group. Forster went on to pre-eminence, rather more than Sickert did, although the visual artist’s influence is felt, as the exhibition demonstrates, on generations of later painters, especially in England. The exhibition is also good in showing the young Sickert’s obvious admiration for both his teacher and for Degas. He attempts drawing in Whistler’s style and paints seascapes and urban landscapes and, later in life, attempts the unusual compositional style of Degas. The latter is most evident in the perspectives in pictures, like Trapeze ( so very close to Degas’ Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando

The exhibition is also good in showing the young Sickert’s obvious admiration for both his teacher and for Degas. He attempts drawing in Whistler’s style and paints seascapes and urban landscapes and, later in life, attempts the unusual compositional style of Degas. The latter is most evident in the perspectives in pictures, like Trapeze ( so very close to Degas’ Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando ) and the subject matter – the circus, the music hall and the demi-monde of Paris and London. When considering the paintings, comparisons favour the Frenchman ( and, indeed, the American ) in my view. That said, Sickert produced some wonderful art, very much in his own style. I especially liked his music hall paintings, where the effects of light and the gilded, glistening interiors of the theatres are captured so well. I also enjoyed his urban landscapes.

) and the subject matter – the circus, the music hall and the demi-monde of Paris and London. When considering the paintings, comparisons favour the Frenchman ( and, indeed, the American ) in my view. That said, Sickert produced some wonderful art, very much in his own style. I especially liked his music hall paintings, where the effects of light and the gilded, glistening interiors of the theatres are captured so well. I also enjoyed his urban landscapes. He chose to paint the music hall, rather than the more prestigious venues and concentrated on ordinary urban life, purchasing studios in the 1890s and early 1900s in working class areas the better to draw and paint everyday existence. I also like his way with a single light source, in evidence in the ‘music hall’ pictures but also in little gems like The Acting Manager, a small sketch for a larger painting, found near the beginning of the exhibition.

He chose to paint the music hall, rather than the more prestigious venues and concentrated on ordinary urban life, purchasing studios in the 1890s and early 1900s in working class areas the better to draw and paint everyday existence. I also like his way with a single light source, in evidence in the ‘music hall’ pictures but also in little gems like The Acting Manager, a small sketch for a larger painting, found near the beginning of the exhibition. I liked the solo nudes of ordinary women, often middle-aged and recumbent in non-classical poses, which, clearly, were influential upon later artists, most notably Lucien Freud. Sickert’s heavy impasto style is a forerunner of Bomberg, Auerbach and Gerhardt Richter. I also enjoyed his later paintings with more use of colour, like Brighton Pierrots and his interest in using photographs and photography in his art. In the twenties Sickert mentored and championed the artists in the East London Group; often untutored, working class individuals with little formal education. He encouraged and showed alongside them.

I liked the solo nudes of ordinary women, often middle-aged and recumbent in non-classical poses, which, clearly, were influential upon later artists, most notably Lucien Freud. Sickert’s heavy impasto style is a forerunner of Bomberg, Auerbach and Gerhardt Richter. I also enjoyed his later paintings with more use of colour, like Brighton Pierrots and his interest in using photographs and photography in his art. In the twenties Sickert mentored and championed the artists in the East London Group; often untutored, working class individuals with little formal education. He encouraged and showed alongside them. when researching this article that I discovered the generous patron, the committed supporter of the working class and documentary realism, the teacher ( at Westminster, where David Bomberg was one of his pupils ) and, ultimately, the establishment man – he was President of the Royal Society of British Artists and a Royal Academician, though, typically, he resigned his RA status on a point of principle. I had thought of Sickert as a flamboyant, self-publicising former actor, now I think of him as a guiding force, a helping hand to modern British painting. I don’t know why the exhibition didn’t bring that out more. Perhaps there was a reluctance to focus on the man – in the past much has been made of Sickert’s own interest in Jack the Ripper and Patricia Cornwell’s claim that he was the infamous Jack. Perhaps the curators wanted to concentrate instead on the paintings – entirely understandable.

when researching this article that I discovered the generous patron, the committed supporter of the working class and documentary realism, the teacher ( at Westminster, where David Bomberg was one of his pupils ) and, ultimately, the establishment man – he was President of the Royal Society of British Artists and a Royal Academician, though, typically, he resigned his RA status on a point of principle. I had thought of Sickert as a flamboyant, self-publicising former actor, now I think of him as a guiding force, a helping hand to modern British painting. I don’t know why the exhibition didn’t bring that out more. Perhaps there was a reluctance to focus on the man – in the past much has been made of Sickert’s own interest in Jack the Ripper and Patricia Cornwell’s claim that he was the infamous Jack. Perhaps the curators wanted to concentrate instead on the paintings – entirely understandable. I hadn’t appreciated the level of sophistication of the dwellers in this land from about 6,000 to 4,000 years ago. The world-view of the earliest, revolving around nature and the seasons, like many hunter-gatherer people, was shared across northern Europe. Of course, until about 6500 BCE and the rising of post Ice Age sea levels, the UK was part of the landmass of that continent. Although subsequently an island archipelago, the peoples who lived here had regular contact with their counterparts on the mainland. This can be seen in their art and craftwork, but also measured by their DNA. One of the most striking examples of this was of the Amesbury Archer. Bones belonging to this man, buried with his bow, were DNA tested. He was originally from the southern Alpine region, though he had lived in southern England for most of his life. Near his grave is that of another, younger man who shares the first’s DNA and is likely to have been his grandson. This man was born and lived most of his life in the Alps, but he was clearly in Amesbury when he met his end. A family visit? Or did the grandson come to live with his grandparents?

I hadn’t appreciated the level of sophistication of the dwellers in this land from about 6,000 to 4,000 years ago. The world-view of the earliest, revolving around nature and the seasons, like many hunter-gatherer people, was shared across northern Europe. Of course, until about 6500 BCE and the rising of post Ice Age sea levels, the UK was part of the landmass of that continent. Although subsequently an island archipelago, the peoples who lived here had regular contact with their counterparts on the mainland. This can be seen in their art and craftwork, but also measured by their DNA. One of the most striking examples of this was of the Amesbury Archer. Bones belonging to this man, buried with his bow, were DNA tested. He was originally from the southern Alpine region, though he had lived in southern England for most of his life. Near his grave is that of another, younger man who shares the first’s DNA and is likely to have been his grandson. This man was born and lived most of his life in the Alps, but he was clearly in Amesbury when he met his end. A family visit? Or did the grandson come to live with his grandparents? beautiful. Perfectly carved and turned stones, with elaborate patterning, these weren’t to be used for everyday, but were ceremonial and included in burials. I was fascinated by one aspect of that early culture, that ‘art’ lay in the act of creation, not, or not only, in the item produced by it. Thus, things did not have the same value as the ability to create them, which seems an eminently sensible value system to me. There is also a wonderful, finely wrought golden collar from this era. Gold was used, not because it had any intrinsic value, but because it was the colour of and reflected the light from, the sun.

beautiful. Perfectly carved and turned stones, with elaborate patterning, these weren’t to be used for everyday, but were ceremonial and included in burials. I was fascinated by one aspect of that early culture, that ‘art’ lay in the act of creation, not, or not only, in the item produced by it. Thus, things did not have the same value as the ability to create them, which seems an eminently sensible value system to me. There is also a wonderful, finely wrought golden collar from this era. Gold was used, not because it had any intrinsic value, but because it was the colour of and reflected the light from, the sun. The exhibition explains, through artefacts, how that culture changed, with the introduction of farming and a concentration on animals and other aspects of nature as a commodity. Art was still relatively fluid, in that stone carvings were made outside and weren’t ‘finished’ objects, but people added to them all the time. This is also true of Stonehenge itself. The landscape in which it was built was already crossed by ceremonial ditches and banks and, after the great sarsen stones were raised, carved on mortice and tenon principles ( see photograph, left) it was added to years later with blue stones brought from Wales, over 220 miles away.

The exhibition explains, through artefacts, how that culture changed, with the introduction of farming and a concentration on animals and other aspects of nature as a commodity. Art was still relatively fluid, in that stone carvings were made outside and weren’t ‘finished’ objects, but people added to them all the time. This is also true of Stonehenge itself. The landscape in which it was built was already crossed by ceremonial ditches and banks and, after the great sarsen stones were raised, carved on mortice and tenon principles ( see photograph, left) it was added to years later with blue stones brought from Wales, over 220 miles away. on Troy. This exhibition places the British pieces in that cross-cultural context, with a collection of armour, roughly contemporaneous to the Illiad and not dissimilar to that worn in ancient Greece (though the helmets look more like Janissaries). There were also exquisite golden drinking bowls and fine copper horsehead artefacts (the horse featured strongly as did the snake, the bird and the sun and moon ). This was a culture close to nature, even when that nature was largely tamed.

on Troy. This exhibition places the British pieces in that cross-cultural context, with a collection of armour, roughly contemporaneous to the Illiad and not dissimilar to that worn in ancient Greece (though the helmets look more like Janissaries). There were also exquisite golden drinking bowls and fine copper horsehead artefacts (the horse featured strongly as did the snake, the bird and the sun and moon ). This was a culture close to nature, even when that nature was largely tamed. the time of the lunar month. This shows a level of sophistication in understanding of the movement of the stars and planets which is reinforced when one sees how many barrows and henges were aligned with sun and, or, moon. The exhibition ranges across many of these, from Denmark, Ireland, the islands of Scotland as well as Wales, Spain, France and elsewhere in England. It also shows how the sea began to play a greater and greater role in the culture of the people living here, as trading took place and the sea itself became a place to worship. There is a recreation of the remarkable Seahenge discovered in the saltmarsh of the Norfolk coast and which, incidentally, features in the crime fiction of Elly Griffiths’ Ruth Galloway books.

the time of the lunar month. This shows a level of sophistication in understanding of the movement of the stars and planets which is reinforced when one sees how many barrows and henges were aligned with sun and, or, moon. The exhibition ranges across many of these, from Denmark, Ireland, the islands of Scotland as well as Wales, Spain, France and elsewhere in England. It also shows how the sea began to play a greater and greater role in the culture of the people living here, as trading took place and the sea itself became a place to worship. There is a recreation of the remarkable Seahenge discovered in the saltmarsh of the Norfolk coast and which, incidentally, features in the crime fiction of Elly Griffiths’ Ruth Galloway books. … but the singing of songs. St Paul’s Opera, Clapham, presented the Big Birthday Bash last Friday and great fun was had by all, as much on stage as in the audience.

… but the singing of songs. St Paul’s Opera, Clapham, presented the Big Birthday Bash last Friday and great fun was had by all, as much on stage as in the audience. Opera and classical favourites, mostly ‘big tunes’, formed the first half of the evening’s entertainment, followed by cabaret and show tunes in the second. Two Australians, a Greek and a Latvian as well as those native to these British Isles formed the company for the evening, several prize-winners among them. The singers were current and former members of SPO, clad in their shiny best (and that was the baritone’s black satin suit). A theme reflected in the audience by SPO super-fan Teresa, in her sparkly rainbow biker jacket. Puccini and Rossini formed the backbone of the first half, spiced with Lehar, Bizet, Leoncavallo and Strauss with one Mozart piece to add a touch of the sublime. It ended with Brindisi, the famous drinking song from La Traviata. Post interval ( more wine, that song was prophetic, and meeting yet more friends and neighbours ) there was Offenbach, Britten and Bernstein, plus Cole Porter, Rogers & Hammerstein and Sondheim.

Opera and classical favourites, mostly ‘big tunes’, formed the first half of the evening’s entertainment, followed by cabaret and show tunes in the second. Two Australians, a Greek and a Latvian as well as those native to these British Isles formed the company for the evening, several prize-winners among them. The singers were current and former members of SPO, clad in their shiny best (and that was the baritone’s black satin suit). A theme reflected in the audience by SPO super-fan Teresa, in her sparkly rainbow biker jacket. Puccini and Rossini formed the backbone of the first half, spiced with Lehar, Bizet, Leoncavallo and Strauss with one Mozart piece to add a touch of the sublime. It ended with Brindisi, the famous drinking song from La Traviata. Post interval ( more wine, that song was prophetic, and meeting yet more friends and neighbours ) there was Offenbach, Britten and Bernstein, plus Cole Porter, Rogers & Hammerstein and Sondheim. Highlights? There were many. Lyric tenor Martins Smaukstelis singing ‘Maria’ from West Side Story – ‘knocked it out the park’ said my American neighbour; the aforementioned Mozart ‘Soave sia il vento’ from Cosi fan Tutti sung by Tanya Hurst, Alexandra Dinwiddie and Louis Hurst and birthday girl and SPO co-founder Patricia Ninian singing ‘Glitter and be Gay’ from Candide.

Highlights? There were many. Lyric tenor Martins Smaukstelis singing ‘Maria’ from West Side Story – ‘knocked it out the park’ said my American neighbour; the aforementioned Mozart ‘Soave sia il vento’ from Cosi fan Tutti sung by Tanya Hurst, Alexandra Dinwiddie and Louis Hurst and birthday girl and SPO co-founder Patricia Ninian singing ‘Glitter and be Gay’ from Candide. Theatre on 21st February about establishing this favourite local opera company from scratch. Unfortunately I’m unable to attend, but I will be going to the the Masterclass at St Paul’s by David Butt Philip (Sydney Opera, the NY Met and Wiener Stadtsoper) on 3rd March – tickets £10. He will also be performing a Gala concert with some friends, Lauren Fagan, Stephanie Wake-Edwards and David Shipley, all alumni of the Royal Opera’s Young Artist Programme. This takes place on Thursday 24th March, tickets £30. I imagine that all these events will be very popular, so buy early.

Theatre on 21st February about establishing this favourite local opera company from scratch. Unfortunately I’m unable to attend, but I will be going to the the Masterclass at St Paul’s by David Butt Philip (Sydney Opera, the NY Met and Wiener Stadtsoper) on 3rd March – tickets £10. He will also be performing a Gala concert with some friends, Lauren Fagan, Stephanie Wake-Edwards and David Shipley, all alumni of the Royal Opera’s Young Artist Programme. This takes place on Thursday 24th March, tickets £30. I imagine that all these events will be very popular, so buy early.