Yesterday I went to the British Museum to catch the Peru exhibition before it closes on 20th February. This relatively small but very interesting exhibition is in the Great Court Gallery (above the Reading Room) and is organised in conjunction with the Museo de Arte de Lima. It brings together artefacts from the BM’s own collection with those from Peru and elsewhere to reveal the history, beliefs and culture of a series of South American societies and peoples from BCE to the sixteenth century arrival of the conquistadors.

Yesterday I went to the British Museum to catch the Peru exhibition before it closes on 20th February. This relatively small but very interesting exhibition is in the Great Court Gallery (above the Reading Room) and is organised in conjunction with the Museo de Arte de Lima. It brings together artefacts from the BM’s own collection with those from Peru and elsewhere to reveal the history, beliefs and culture of a series of South American societies and peoples from BCE to the sixteenth century arrival of the conquistadors.

My knowledge of such societies was restricted to Schaffer’s 1964 play The Royal Hunt of the Sun, numerous bloodthirsty films and cartoons from childhood, the wonderful Royal Academy exhibition of the 90s on the Aztecs (from a different part of south America completely) and, perhaps most personally, the Palacio del Conde de los Andes in Jerez de la Frontera, which belonged to the last Viceroy of Peru. This exhibition has expanded it enormously, covering as it does the period between 2500 BCE and the 1500s, tropical forests, arid plains and, above all, the Andes, a geographical region centred on Peru, but including Argentina, Bolivia, Columbia and Ecuador. I was completely ignorant of the people who lived at Chavin de Huantar (1200BCE) who made the remarkable gold headdress and earrings (right). Theirs was a site of pilgrimage to an oracle. In southern Peru archeologists discovered the funerary goods of the Paracas people (900BCE) who were followed by the more famous Nascas (200BCE-600CE) with their amazing and huge geoglyphs, which can only be seen in their entirety from the sky.

perhaps most personally, the Palacio del Conde de los Andes in Jerez de la Frontera, which belonged to the last Viceroy of Peru. This exhibition has expanded it enormously, covering as it does the period between 2500 BCE and the 1500s, tropical forests, arid plains and, above all, the Andes, a geographical region centred on Peru, but including Argentina, Bolivia, Columbia and Ecuador. I was completely ignorant of the people who lived at Chavin de Huantar (1200BCE) who made the remarkable gold headdress and earrings (right). Theirs was a site of pilgrimage to an oracle. In southern Peru archeologists discovered the funerary goods of the Paracas people (900BCE) who were followed by the more famous Nascas (200BCE-600CE) with their amazing and huge geoglyphs, which can only be seen in their entirety from the sky.

In northern Peru the Moche people (100-800 CE), fabulous ceramicists (see figure of a Moche warrior, left), concentrated along the coasts and river valleys, while the Wari (600-900CE) developed in the Ayacucho region and expanded to cover the southern highlands and the northern coast. Then, between the 10th and 12th centuries the Kingdom of Chimu dominated, its capital Chan Chan having a population of up to 75,000 people. In the central Andes the Inca empire emerged in about 1400, expanding its territory throughout the region, via a system of roads and waterways between diverse cultures and communities. This included the creation of the mountain fastness which is Machu Pichu, or ‘ancient mountain’, including about 200 polished stone buildings, as well as terraces and pyramids. Though this was not the Inca capital, which was at Cusco.

In northern Peru the Moche people (100-800 CE), fabulous ceramicists (see figure of a Moche warrior, left), concentrated along the coasts and river valleys, while the Wari (600-900CE) developed in the Ayacucho region and expanded to cover the southern highlands and the northern coast. Then, between the 10th and 12th centuries the Kingdom of Chimu dominated, its capital Chan Chan having a population of up to 75,000 people. In the central Andes the Inca empire emerged in about 1400, expanding its territory throughout the region, via a system of roads and waterways between diverse cultures and communities. This included the creation of the mountain fastness which is Machu Pichu, or ‘ancient mountain’, including about 200 polished stone buildings, as well as terraces and pyramids. Though this was not the Inca capital, which was at Cusco.

The Incas were eventually deposed by the Spanish, led by Pizarro and a brutal repression of indigenous ways of life followed. It is Pizarro’s first encounter and subsequent relationship with the Inca Emperor Atahuallpa which features in the aforementioned play (and film). The exhibition included artefacts from the colonial period, though not many of them.

ways of life followed. It is Pizarro’s first encounter and subsequent relationship with the Inca Emperor Atahuallpa which features in the aforementioned play (and film). The exhibition included artefacts from the colonial period, though not many of them.

What I found fascinating about the peoples living in these regions was that they developed art and technology (the roads and waterways across the Andes for example) without a system of writing. Rather they used a system of khipu to transmit information – knotted textiles. I imagine that they also had an oral tradition of storytelling, most ancient societies did, but, because these stories were never written down these would have been lost.  They certainly had complex belief systems, centred on nature and the land, as shown by the exquisite ceramics in the form of felines and serpents (see left). It also included blood sacrifice (back to those childhood bloodthirsty yarns) with any prisoners captured during wars being slain as a sacrifice to the gods of the land. One funerary robe included no fewer than seventy four human figures in its border and central pattern, each of them carrying a severed human head. Ceramics and musical instruments were decorated with similarly gruesome patterns. The exhibition includes a number of sculptures of captured prisoners, roped and awaiting their fate.

They certainly had complex belief systems, centred on nature and the land, as shown by the exquisite ceramics in the form of felines and serpents (see left). It also included blood sacrifice (back to those childhood bloodthirsty yarns) with any prisoners captured during wars being slain as a sacrifice to the gods of the land. One funerary robe included no fewer than seventy four human figures in its border and central pattern, each of them carrying a severed human head. Ceramics and musical instruments were decorated with similarly gruesome patterns. The exhibition includes a number of sculptures of captured prisoners, roped and awaiting their fate.

If you get the opportunity, do visit this exhibition before it closes. It isn’t huge, but leave yourself plenty of time, there’s a lot to absorb. Entry costs £17, with some £14.80 concessions.

Boring, right?

Boring, right? there, fronting a Tesco store and apartments. This has been extended to incorporate another ‘wing’ which was in the extension plans for the 1930s but never built, replacing one of the original old houses, Preston House, of which the hospital was comprised.

there, fronting a Tesco store and apartments. This has been extended to incorporate another ‘wing’ which was in the extension plans for the 1930s but never built, replacing one of the original old houses, Preston House, of which the hospital was comprised. Anderson Hospital, founded 1872) on the Euston Road, the first hospital in the UK to be staffed entirely by women. But by the early years of the century demand hugely outstripped the ability of this hospital to cope and so the South London was proposed. An astonishingly successful fund-raising campaign began and properties at Clapham South were purchased and converted. The hospital opened its doors in 1912.

Anderson Hospital, founded 1872) on the Euston Road, the first hospital in the UK to be staffed entirely by women. But by the early years of the century demand hugely outstripped the ability of this hospital to cope and so the South London was proposed. An astonishingly successful fund-raising campaign began and properties at Clapham South were purchased and converted. The hospital opened its doors in 1912. the inside of the buildings altered radically between 1912 and 1935 (when the Cooper building was built). The archivist provided me with an Ordnance Survey map and a large bundle of drainage plans, covering those for the original conversion of private houses to hospital, through various extensions, to the 1930s plans. I had to put them into some sort of order and understand how they fitted together. Fortunately for me they were dated (though what the plans showed, exactly, wasn’t always immediately clear).

the inside of the buildings altered radically between 1912 and 1935 (when the Cooper building was built). The archivist provided me with an Ordnance Survey map and a large bundle of drainage plans, covering those for the original conversion of private houses to hospital, through various extensions, to the 1930s plans. I had to put them into some sort of order and understand how they fitted together. Fortunately for me they were dated (though what the plans showed, exactly, wasn’t always immediately clear). on how the water and waste drained away to the sewers. There was some of that, but there was a lot more as well. There is water throughout a building, especially a hospital and it has to drain away, so the plans covered all the floors, even the fourth, showing all the ‘water features’ sinks, baths, sluices etc.. I was pleased to see that even the servants rooms had hand washing basins, although they didn’t have en suite bathrooms. Those were communal at the end of the corridor.

on how the water and waste drained away to the sewers. There was some of that, but there was a lot more as well. There is water throughout a building, especially a hospital and it has to drain away, so the plans covered all the floors, even the fourth, showing all the ‘water features’ sinks, baths, sluices etc.. I was pleased to see that even the servants rooms had hand washing basins, although they didn’t have en suite bathrooms. Those were communal at the end of the corridor. There was also a staff dining room or canteen and a School of Nursing. The grounds included gardens, a tennis court and, from the 30s again, a block providing nurses’ accommodation, including sitting rooms and a recreation area. I recall walking past the block along Hazelbourne Road on my way to and from the tube every morning when I first moved to London. How I wish that I had taken photographs, but camera phones weren’t invented then. Nonetheless, the plans gave me lots of information and I’ve begun to build a picture of what life there may have been like.

There was also a staff dining room or canteen and a School of Nursing. The grounds included gardens, a tennis court and, from the 30s again, a block providing nurses’ accommodation, including sitting rooms and a recreation area. I recall walking past the block along Hazelbourne Road on my way to and from the tube every morning when I first moved to London. How I wish that I had taken photographs, but camera phones weren’t invented then. Nonetheless, the plans gave me lots of information and I’ve begun to build a picture of what life there may have been like. still finding interesting places new to me, sometimes close to home. Ten days ago I found myself in Stockwell.

still finding interesting places new to me, sometimes close to home. Ten days ago I found myself in Stockwell. Leisure Magazine. It was somewhat daunting, to be interviewing the man who had interviewed so many famous, and infamous, people and whose voice had formed part of the backdrop to my mornings for so many years. Stourton was a main presenter on Radio 4’s Today Programme for a decade – as well as The World at One and The World This Weekend, both of which he still does on occasion.

Leisure Magazine. It was somewhat daunting, to be interviewing the man who had interviewed so many famous, and infamous, people and whose voice had formed part of the backdrop to my mornings for so many years. Stourton was a main presenter on Radio 4’s Today Programme for a decade – as well as The World at One and The World This Weekend, both of which he still does on occasion. not to be late, I was ridiculously early. So I wandered towards the address I had been given and discovered, for the first time, Stockwell Park or the Stockwell Conservation Area. It received that designation in 1973 and covers the old Stockwell Green (the 15th century manor house which formerly stood there has links with Thomas Cromwell) and the later 19th century developments of Stockwell Crescent and the roads running from it. Built primarily in the 1830s the surviving buildings are elegant early Victorian villas with gardens. They were built to different designs, which distinguishes them from the smaller, ‘pattern built’ south London Victoriana elsewhere (like some of my beloved Clapham).

not to be late, I was ridiculously early. So I wandered towards the address I had been given and discovered, for the first time, Stockwell Park or the Stockwell Conservation Area. It received that designation in 1973 and covers the old Stockwell Green (the 15th century manor house which formerly stood there has links with Thomas Cromwell) and the later 19th century developments of Stockwell Crescent and the roads running from it. Built primarily in the 1830s the surviving buildings are elegant early Victorian villas with gardens. They were built to different designs, which distinguishes them from the smaller, ‘pattern built’ south London Victoriana elsewhere (like some of my beloved Clapham). found St Michael’s Church of England church (consecrated 1841) and a blue plaque marking the home of Lillian Bayliss, Director of the Old Vic and Sadlers Wells theatres and founder of the forerunners of the English National Opera, the National Theatre and the Royal Ballet. The whole enclave was a delight and so very near to the busy Stockwell Road which runs directly into the City. I never knew it existed.

found St Michael’s Church of England church (consecrated 1841) and a blue plaque marking the home of Lillian Bayliss, Director of the Old Vic and Sadlers Wells theatres and founder of the forerunners of the English National Opera, the National Theatre and the Royal Ballet. The whole enclave was a delight and so very near to the busy Stockwell Road which runs directly into the City. I never knew it existed.

Yesterday to the British Museum during the last week of the exhibition Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint which ends on Sunday. It’s an interesting exhibition which follows Becket’s upbringing, fairly meteoric career ( from Cheapside immigrant merchant’s son to the Archbishopric and Lord Chancellorship of England ) to his eventual death and subsequent canonisation. I reread Murder in the Cathedral in preparation and the exhibition ends with lines from that verse play.

Yesterday to the British Museum during the last week of the exhibition Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint which ends on Sunday. It’s an interesting exhibition which follows Becket’s upbringing, fairly meteoric career ( from Cheapside immigrant merchant’s son to the Archbishopric and Lord Chancellorship of England ) to his eventual death and subsequent canonisation. I reread Murder in the Cathedral in preparation and the exhibition ends with lines from that verse play. seemed to me and my companion, also sought martyrdom as the ultimate step, a translation into immortality. Everyone knows the story, or has seen the film and recognises the famous quote ‘Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?’, although this is, without explanation, changed to ‘Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?’ in this exhibition.

seemed to me and my companion, also sought martyrdom as the ultimate step, a translation into immortality. Everyone knows the story, or has seen the film and recognises the famous quote ‘Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?’, although this is, without explanation, changed to ‘Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?’ in this exhibition.  British Museum curators shouldn’t, in my view, be saying it is because, aside from anything else, it will then become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Three young people, unknown to me, but who went round the exhibition at approximately the same time as I did, clearly took away this ‘story’ without its context. Henry might not be a popular, or even a colourful, character, by all accounts he was a choleric and sometimes harsh individual, but he also inherited a cash-strapped and exhausted land, following the war between Stephen and Matilda ( Henry’s mother ). Just because he isn’t particularly likeable doesn’t mean his role in history should be limited to his role in a martyrdom. In my humble opinion, it’s bad history ( even if it is good story telling. ) The richness and complexity of life, even life in the past, is reduced in this way. Rant over.

British Museum curators shouldn’t, in my view, be saying it is because, aside from anything else, it will then become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Three young people, unknown to me, but who went round the exhibition at approximately the same time as I did, clearly took away this ‘story’ without its context. Henry might not be a popular, or even a colourful, character, by all accounts he was a choleric and sometimes harsh individual, but he also inherited a cash-strapped and exhausted land, following the war between Stephen and Matilda ( Henry’s mother ). Just because he isn’t particularly likeable doesn’t mean his role in history should be limited to his role in a martyrdom. In my humble opinion, it’s bad history ( even if it is good story telling. ) The richness and complexity of life, even life in the past, is reduced in this way. Rant over. as the murder itself. I was intrigued to find out about the broken sword and the depiction which showed this, as well as a chunk of skull falling to the flagstones of the cathedral floor. It’s interesting that these small, if gory, details survived and thrived in later representations of the scene. I was surprised by the far-flung examples of the Becket cult – stone carving from Sweden, a reliquary from Norway, reference in a parchment from Italy. Maybe I shouldn’t have been, the Church stretched across Europe and its saints were promoted widely.

as the murder itself. I was intrigued to find out about the broken sword and the depiction which showed this, as well as a chunk of skull falling to the flagstones of the cathedral floor. It’s interesting that these small, if gory, details survived and thrived in later representations of the scene. I was surprised by the far-flung examples of the Becket cult – stone carving from Sweden, a reliquary from Norway, reference in a parchment from Italy. Maybe I shouldn’t have been, the Church stretched across Europe and its saints were promoted widely. As readers of Plague will know London hosts many a Roman remnant, from the baths beneath the West End to the Temple of Mithras underneath the Bank of England, but on Friday last I went to see those currently on show at the British Museum in the exhibition Nero: the man behind the myth.

As readers of Plague will know London hosts many a Roman remnant, from the baths beneath the West End to the Temple of Mithras underneath the Bank of England, but on Friday last I went to see those currently on show at the British Museum in the exhibition Nero: the man behind the myth.  for nine days – but he wasn’t alone in doing so. He did commit murders, at least indirectly – first century Roman palace power plays were brutal and murderous. There is evidence, however, that he cared about the people of the city – he instigated relief efforts after the Great Fire, offering shelter in his own palaces and organising food supplies and he started a very large rebuilding programme soon after. It’s almost certain that he was innocent of initiating the fire. The plebs certainly thought better of him than their Senatorial ‘betters’, Nero’s is the imperial name most often found in positive ancient graffiti. He improved the road to Ostia, Rome’s harbour where the grain shipments arrived, so as to protect the city’s food supply and insisted that the rebuilt Rome had better standards of housing. So, not all bad then.

for nine days – but he wasn’t alone in doing so. He did commit murders, at least indirectly – first century Roman palace power plays were brutal and murderous. There is evidence, however, that he cared about the people of the city – he instigated relief efforts after the Great Fire, offering shelter in his own palaces and organising food supplies and he started a very large rebuilding programme soon after. It’s almost certain that he was innocent of initiating the fire. The plebs certainly thought better of him than their Senatorial ‘betters’, Nero’s is the imperial name most often found in positive ancient graffiti. He improved the road to Ostia, Rome’s harbour where the grain shipments arrived, so as to protect the city’s food supply and insisted that the rebuilt Rome had better standards of housing. So, not all bad then.  look at the historical sources. That Nero was ruthless and brutal – well, which Emperor could have ruled Rome for fourteen tumultuous years if he hadn’t been? That he ‘fiddled while Rome burned’ or at least played a lyre, comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio, historians writing during the age of later emperors and whose interests were served by making their masters look good in comparison. Tacitus, who was actually alive at the time of the fire, places Nero outside Rome when the fire happened. Given the title of the exhibition I was hoping there would be more exploration of how and why myths like those surrounding Nero were formed and how common ‘stories’ sometimes reveal a deeper truth, but that wasn’t where this was going.

look at the historical sources. That Nero was ruthless and brutal – well, which Emperor could have ruled Rome for fourteen tumultuous years if he hadn’t been? That he ‘fiddled while Rome burned’ or at least played a lyre, comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio, historians writing during the age of later emperors and whose interests were served by making their masters look good in comparison. Tacitus, who was actually alive at the time of the fire, places Nero outside Rome when the fire happened. Given the title of the exhibition I was hoping there would be more exploration of how and why myths like those surrounding Nero were formed and how common ‘stories’ sometimes reveal a deeper truth, but that wasn’t where this was going. One story I’ve come across, though I’m not sure how true it is, is about his meeting with the Pythia of Delphi. Nero toured Greece in CE 66/67 when he granted the Greeks their ‘freedom’ ( largely from the steep taxes Rome imposed upon client peoples ) and took part in the Isthmian Games. Like anyone who was anyone in the ancient world, he went to Delphi. The Pythia forbade his entry to the Temple of Apollo, calling him a matricide and telling him that the number 73 would mark the hour of his downfall. He had her burned alive ( or so Dio Cassius says ) but took her words to mean that he would live until a ripe old age. In fact he was deposed only a year or so later, by the general, later Emperor, Galba, who happened to be 73 years old at the time ( or so the story goes ). What to take from this, other than not to cross a pythia, I’m not at all sure, but then, all stories about the Pythia tend to show how she was right in the end. Not much consolation when you’re killed horribly. It makes the murder in Oracle look tame in comparison.

One story I’ve come across, though I’m not sure how true it is, is about his meeting with the Pythia of Delphi. Nero toured Greece in CE 66/67 when he granted the Greeks their ‘freedom’ ( largely from the steep taxes Rome imposed upon client peoples ) and took part in the Isthmian Games. Like anyone who was anyone in the ancient world, he went to Delphi. The Pythia forbade his entry to the Temple of Apollo, calling him a matricide and telling him that the number 73 would mark the hour of his downfall. He had her burned alive ( or so Dio Cassius says ) but took her words to mean that he would live until a ripe old age. In fact he was deposed only a year or so later, by the general, later Emperor, Galba, who happened to be 73 years old at the time ( or so the story goes ). What to take from this, other than not to cross a pythia, I’m not at all sure, but then, all stories about the Pythia tend to show how she was right in the end. Not much consolation when you’re killed horribly. It makes the murder in Oracle look tame in comparison. fascinating bunch, they still exert a celebrity-style, dark and seductive glamour even today, that it’s engaging. Some of the exhibits are exquisite – the jewellery, for example, or gruesome – the heavy slave chains, or the gladiator armour and the visitor forms a more rounded picture of the emperor, much more nuanced than the popular myth would have us believe. A good exhibition, worth visiting, that will make you reassess your understanding of Nero, but prepare to concentrate, there are a lot of coins.

fascinating bunch, they still exert a celebrity-style, dark and seductive glamour even today, that it’s engaging. Some of the exhibits are exquisite – the jewellery, for example, or gruesome – the heavy slave chains, or the gladiator armour and the visitor forms a more rounded picture of the emperor, much more nuanced than the popular myth would have us believe. A good exhibition, worth visiting, that will make you reassess your understanding of Nero, but prepare to concentrate, there are a lot of coins.

I’ve recently been out and about looking at the places in London where the third book in the Cassandra Fortune series, entitled ‘Opera‘, is set. The obvious one, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, is not yet open to anyone but ticket holders to socially distanced performances ( though I have a contact there for when it opens more widely ), but there are others, less obvious and, to non-Londoners, perhaps something of a revelation. If ‘Plague‘ was set in places that we all know, even if it took you to parts of those places which are usually closed to view, or hidden, ‘Opera’ will introduce some settings which are less well-known, but, I hope, people may then visit.

I’ve recently been out and about looking at the places in London where the third book in the Cassandra Fortune series, entitled ‘Opera‘, is set. The obvious one, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, is not yet open to anyone but ticket holders to socially distanced performances ( though I have a contact there for when it opens more widely ), but there are others, less obvious and, to non-Londoners, perhaps something of a revelation. If ‘Plague‘ was set in places that we all know, even if it took you to parts of those places which are usually closed to view, or hidden, ‘Opera’ will introduce some settings which are less well-known, but, I hope, people may then visit.

Brompton is one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ Victorian cemeteries, which includes Highgate, with its graves of Karl Marx, George Eliot and other very famous people and Kelsall Green with its oft-filmed catacombs. While well known to locals – and a godsend during lockdowns – it is less widely known than these others. Both Kelsall Green and Tower Hamlets ( another Magnificent Seven cemetery ) featured in ‘Plague’. Brompton is owned by the Crown and run by The Royal Parks and includes many military graves, including of Commonwealth service personnel maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and many Czechoslovak, Polish and Russian military burials. It is also evidence of the diversity of Victorian London, housing as it did and does, the remains of individuals ranging from Chief Long Wolf of the Ogulala Sioux nation to Johannes Zukertorte, Jewish-Polish chess grandmaster and the Keeley and Vokes families, music hall artistes and actors. Other individuals buried here include a Mr Nutkin, Mr Brock, Mr Tod, Jeremiah Fisher and Peter Rabbett – Beatrix Potter lived nearby and was known to walk in the cemetery often, did these names inspire her?

Brompton is one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ Victorian cemeteries, which includes Highgate, with its graves of Karl Marx, George Eliot and other very famous people and Kelsall Green with its oft-filmed catacombs. While well known to locals – and a godsend during lockdowns – it is less widely known than these others. Both Kelsall Green and Tower Hamlets ( another Magnificent Seven cemetery ) featured in ‘Plague’. Brompton is owned by the Crown and run by The Royal Parks and includes many military graves, including of Commonwealth service personnel maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and many Czechoslovak, Polish and Russian military burials. It is also evidence of the diversity of Victorian London, housing as it did and does, the remains of individuals ranging from Chief Long Wolf of the Ogulala Sioux nation to Johannes Zukertorte, Jewish-Polish chess grandmaster and the Keeley and Vokes families, music hall artistes and actors. Other individuals buried here include a Mr Nutkin, Mr Brock, Mr Tod, Jeremiah Fisher and Peter Rabbett – Beatrix Potter lived nearby and was known to walk in the cemetery often, did these names inspire her? The Chapel at the cemetery’s southern end wasn’t open last week, but the grand colonnade is open all year round. Built in a style aping that of St Peter’s Square in Rome, the Colonnade runs above catacombs, which were fashionable for a brief time in Victorian London ( all too brief, additional catacombs built along the west side of the cemetery were never fully occupied ). The steps down to them are very wide and shallow, mainly because the lead-lined coffins deemed necessary for catacomb interment were extremely heavy and therefore difficult for pallbearers to carry and manoeuvre. The catacombs themselves are not open to the public except on special tours and open days and the locked metal doors, with their sculpted serpentine bas reliefs offer tantalising glimpses within.

The Chapel at the cemetery’s southern end wasn’t open last week, but the grand colonnade is open all year round. Built in a style aping that of St Peter’s Square in Rome, the Colonnade runs above catacombs, which were fashionable for a brief time in Victorian London ( all too brief, additional catacombs built along the west side of the cemetery were never fully occupied ). The steps down to them are very wide and shallow, mainly because the lead-lined coffins deemed necessary for catacomb interment were extremely heavy and therefore difficult for pallbearers to carry and manoeuvre. The catacombs themselves are not open to the public except on special tours and open days and the locked metal doors, with their sculpted serpentine bas reliefs offer tantalising glimpses within. At Delphi it was the Pythia who spoke for the god Apollo – ‘prophet’ or prophetess’ originally meaning ‘spokesperson’. At Cumae it was the similarly Apollonian Sibyl and at Siwah in Egypt another sibyl, supposedly of the line of Poseidon and related to Nile, spoke for Zeus-Ammon. The first two were real women and, unusually for much of the ancient world, women who had power. They were actually a succession of women who filled the ‘office’ of Pythia or Sibyl ( although it is said that the most famous of the latter was granted extra long life and lived until very old, shrunken and wizened ). They certainly helped determine policy. As Cicero says of the Delphic Pythia, there wasn’t a important decision taken in the ancient Greek world without consulting her.

At Delphi it was the Pythia who spoke for the god Apollo – ‘prophet’ or prophetess’ originally meaning ‘spokesperson’. At Cumae it was the similarly Apollonian Sibyl and at Siwah in Egypt another sibyl, supposedly of the line of Poseidon and related to Nile, spoke for Zeus-Ammon. The first two were real women and, unusually for much of the ancient world, women who had power. They were actually a succession of women who filled the ‘office’ of Pythia or Sibyl ( although it is said that the most famous of the latter was granted extra long life and lived until very old, shrunken and wizened ). They certainly helped determine policy. As Cicero says of the Delphic Pythia, there wasn’t a important decision taken in the ancient Greek world without consulting her. The Pythia’s fame was assured and she features in drama, poetry, histories and other writings from about the sixth century BCE onwards ( although there was a priestess of legend supposedly at Delphi before then ). The Sibyl of Cumae may not have been quite as well known, but she had her adherents too, especially in the Roman period, and legendary stories grew up around her. The most famous was probably that involving Tarquin, the supposed last king of Rome, and the Sybilline books. An unknown woman arrived in Rome and offered to sell the king nine books of prophesies. Given the enormous sum she asked for them Tarquin refused to buy. She burnt three of them and asked the same price for the remaining six. Again Tarquin refused and she burned another three. Only three books remained, but Tarquin relented and bought them, for the original asking price for the nine. At which point the woman disappeared and the books were stored in the temple of Capitoline Jove on the Capitol. They were burned in a subsequent fire.

The Pythia’s fame was assured and she features in drama, poetry, histories and other writings from about the sixth century BCE onwards ( although there was a priestess of legend supposedly at Delphi before then ). The Sibyl of Cumae may not have been quite as well known, but she had her adherents too, especially in the Roman period, and legendary stories grew up around her. The most famous was probably that involving Tarquin, the supposed last king of Rome, and the Sybilline books. An unknown woman arrived in Rome and offered to sell the king nine books of prophesies. Given the enormous sum she asked for them Tarquin refused to buy. She burnt three of them and asked the same price for the remaining six. Again Tarquin refused and she burned another three. Only three books remained, but Tarquin relented and bought them, for the original asking price for the nine. At which point the woman disappeared and the books were stored in the temple of Capitoline Jove on the Capitol. They were burned in a subsequent fire. too was visited by Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt and though history doesn’t record how he treated the people there, it does say he went away content. The Siwah Oracle, wisely, forbade its supplicants from discussing what the Oracle had said, which pre-empted the examination of its prophesies which other prophetic Oracles were subject to. Unfortunately this also means we don’t have the wonderful stories about this oracle that we have about the other two. The legendary Sybil at Siwah was supposedly the daughter of Lamia, herself the daughter of Poseidon, God of the sea ( and she appears in Euripides play, Lamia ).

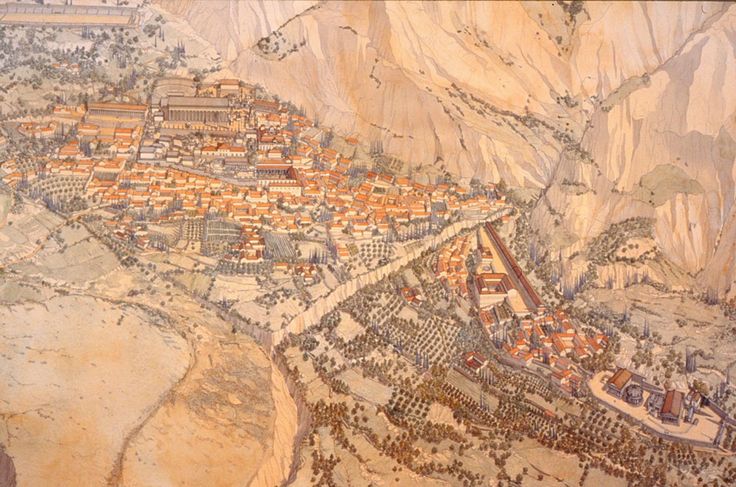

too was visited by Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt and though history doesn’t record how he treated the people there, it does say he went away content. The Siwah Oracle, wisely, forbade its supplicants from discussing what the Oracle had said, which pre-empted the examination of its prophesies which other prophetic Oracles were subject to. Unfortunately this also means we don’t have the wonderful stories about this oracle that we have about the other two. The legendary Sybil at Siwah was supposedly the daughter of Lamia, herself the daughter of Poseidon, God of the sea ( and she appears in Euripides play, Lamia ). In Aethiopica, an ancient novel by Heliodorus, a central character who is a priest of the Egyptian goddess Isis, describes Delphi as where the divine can be found, a natural fortress, beloved of Nature. Other ancient writers commented on its hidden aspect. It’s certainly true that the mountain itself seems to protect the sanctuary, denying the visitor any faraway view, hiding the site until the traveller rounds the last craggy outcrop and sees the Temple nestling in a bowl of the mountain, the harsh, grey granite rising up behind. It must, in the days of its full splendour, have been a truly stunning sight. The marble of its many buildings reflecting the sunlight and glowing golden at dusk as the pilgrims climbed the paths to the Temple, to petition the Oracle of the God Apollo for answers, the last rays of the sun glinting in the gold which topped many of the monuments. It’s still fairly impressive now.

In Aethiopica, an ancient novel by Heliodorus, a central character who is a priest of the Egyptian goddess Isis, describes Delphi as where the divine can be found, a natural fortress, beloved of Nature. Other ancient writers commented on its hidden aspect. It’s certainly true that the mountain itself seems to protect the sanctuary, denying the visitor any faraway view, hiding the site until the traveller rounds the last craggy outcrop and sees the Temple nestling in a bowl of the mountain, the harsh, grey granite rising up behind. It must, in the days of its full splendour, have been a truly stunning sight. The marble of its many buildings reflecting the sunlight and glowing golden at dusk as the pilgrims climbed the paths to the Temple, to petition the Oracle of the God Apollo for answers, the last rays of the sun glinting in the gold which topped many of the monuments. It’s still fairly impressive now. As Nico, an employee of Delphi Museum and a character in my novel, says ‘The temple ruins you’ll see today date back to 320 BCE. It’s the sixth Temple of Apollo to stand here, ‘though the site has been sacred for millenia.’ The Sacred Way, the stone pathway which zigzags across the mountain slope, rising towards the Temple Terrace, is a relatively modern addition, in the 5th and 6th centuries CE and, though this is the route followed by modern visitors, the Temple site BCE would have had several entrances and paths and sets of steps between paths, not unlike those in the town of Delphi today.

As Nico, an employee of Delphi Museum and a character in my novel, says ‘The temple ruins you’ll see today date back to 320 BCE. It’s the sixth Temple of Apollo to stand here, ‘though the site has been sacred for millenia.’ The Sacred Way, the stone pathway which zigzags across the mountain slope, rising towards the Temple Terrace, is a relatively modern addition, in the 5th and 6th centuries CE and, though this is the route followed by modern visitors, the Temple site BCE would have had several entrances and paths and sets of steps between paths, not unlike those in the town of Delphi today. boundary walls constructed in the sixth century BCE. The square addition of the Roman Agora is on the right and the ancient Amphitheatre is directly behind the massive Temple itself. The Temple was the heart of the sanctuary, its Terrace packed with monuments, statuary and other offerings to the God. Many of the box-like buildings you can see on the slopes below it were Treasuries, belonging to city states, islands, countries, where their special offerings were stored. The Treasury of the Athenians, which features in ‘Oracle’ is the best restored. Originally dedicated after the victory at Marathon the restoration took place in the early twentieth century with money raised from the modern city of Athens.

boundary walls constructed in the sixth century BCE. The square addition of the Roman Agora is on the right and the ancient Amphitheatre is directly behind the massive Temple itself. The Temple was the heart of the sanctuary, its Terrace packed with monuments, statuary and other offerings to the God. Many of the box-like buildings you can see on the slopes below it were Treasuries, belonging to city states, islands, countries, where their special offerings were stored. The Treasury of the Athenians, which features in ‘Oracle’ is the best restored. Originally dedicated after the victory at Marathon the restoration took place in the early twentieth century with money raised from the modern city of Athens. version of Golvin’s watercolour. This stands at the bottom right of the picture (right) just beyond the Gymnasium – you can see the long running track – and plunge pool. This was where athletic members of the public would work out and train. The Sanctuary Stadium, where the Pythian Games were held, is much higher up the mountain, its edge can be seen in the top left hand corner of the larger picture. It is from the Stadium that my heroine looks down on the precinct – ‘It was easy to understand why this place had been sacred for so long’ she says. ‘It was so still, a sense of the divine so near to the surface. It had astonishing drama and beauty.’ And it still does.

version of Golvin’s watercolour. This stands at the bottom right of the picture (right) just beyond the Gymnasium – you can see the long running track – and plunge pool. This was where athletic members of the public would work out and train. The Sanctuary Stadium, where the Pythian Games were held, is much higher up the mountain, its edge can be seen in the top left hand corner of the larger picture. It is from the Stadium that my heroine looks down on the precinct – ‘It was easy to understand why this place had been sacred for so long’ she says. ‘It was so still, a sense of the divine so near to the surface. It had astonishing drama and beauty.’ And it still does. various forms of a council representing, at least nominally, all of Greece. There was a decided element of outshining the competition, with cities and other dedicatees, building ‘bigger and better’ than their fellows. Not least of the rivalries was that between Athens and Sparta, as you would expect, but there were others, often reflecting the political tensions of the day. In all there were three Sacred Wars for the prize of virtual overlordship of Delphi, dominating the council, and more than one political enemy was flung from the top of the Phaedriades cliffs as a blasphemer (planting evidence of stolen goods which had been dedicated to the God was a common trick).

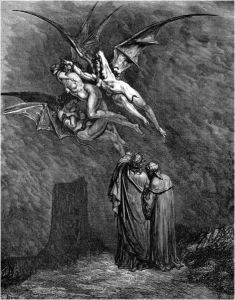

various forms of a council representing, at least nominally, all of Greece. There was a decided element of outshining the competition, with cities and other dedicatees, building ‘bigger and better’ than their fellows. Not least of the rivalries was that between Athens and Sparta, as you would expect, but there were others, often reflecting the political tensions of the day. In all there were three Sacred Wars for the prize of virtual overlordship of Delphi, dominating the council, and more than one political enemy was flung from the top of the Phaedriades cliffs as a blasphemer (planting evidence of stolen goods which had been dedicated to the God was a common trick). Given the antiquity of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and the cultural influence it has had over the millennia it’s not surprising that large numbers of visual artists have been inspired by it. Followers of my twitter feed will know I have been collecting and sharing images of Delphi, the Temple of Apollo and the various historical or mythical beings who came there, drawn or painted by famous artists. So, we’ve had Gustave Dore’s Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes or Furies (left), Edward Lear’s water colour of the Phaedriades, the massive cliffs which loom over the Temple site and William Blake’s illustration for ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ showing ‘The Overthrow of Apollo and the Pagan Gods’.

Given the antiquity of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and the cultural influence it has had over the millennia it’s not surprising that large numbers of visual artists have been inspired by it. Followers of my twitter feed will know I have been collecting and sharing images of Delphi, the Temple of Apollo and the various historical or mythical beings who came there, drawn or painted by famous artists. So, we’ve had Gustave Dore’s Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes or Furies (left), Edward Lear’s water colour of the Phaedriades, the massive cliffs which loom over the Temple site and William Blake’s illustration for ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ showing ‘The Overthrow of Apollo and the Pagan Gods’. events or characters from Greek drama set at Delphi. On Greek redware (right) for example, showing the sleeping Erinyes being roused from their Apollo-induced slumber by the vengeful spirit of Clytemnestra, urging them to hunt down her son, and murderer, Orestes ( from Eumenides by Aeschylus ). Later paintings include Orestes being pursued by the same furies by, among others, John Singer Sergeant, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, John Flaxman and Franz Stuck, until we’re up to date with John Wilson (after Bouguereau).

events or characters from Greek drama set at Delphi. On Greek redware (right) for example, showing the sleeping Erinyes being roused from their Apollo-induced slumber by the vengeful spirit of Clytemnestra, urging them to hunt down her son, and murderer, Orestes ( from Eumenides by Aeschylus ). Later paintings include Orestes being pursued by the same furies by, among others, John Singer Sergeant, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, John Flaxman and Franz Stuck, until we’re up to date with John Wilson (after Bouguereau). own versions, like that in Puck magazine (1877) or in Punch (left). In this instance it is the Rt. Hon. John Bright MP who is in the Orestes role, being pursued by the vested interests which he opposed through the Anti-Corn Law League. It was Bright, famous for his oratorical skills among other things, who coined the phrase ‘Mother of Parliaments’. He is also credited with first using the phrase ‘flogging a dead horse’ to illustrate the pointlessness of certain activities (in Bright’s case this meant getting the House of Commons to consider Parliamentary reform – ’twas ever thus).

own versions, like that in Puck magazine (1877) or in Punch (left). In this instance it is the Rt. Hon. John Bright MP who is in the Orestes role, being pursued by the vested interests which he opposed through the Anti-Corn Law League. It was Bright, famous for his oratorical skills among other things, who coined the phrase ‘Mother of Parliaments’. He is also credited with first using the phrase ‘flogging a dead horse’ to illustrate the pointlessness of certain activities (in Bright’s case this meant getting the House of Commons to consider Parliamentary reform – ’twas ever thus). Wenceslas Holler etched them in the seventeenth century (right) and they have re-emerged in modern day gaming ( though with a rather different, sexy, look which speaks to who it is who plays those games rather than any mythological authenticity ). Naked the furies may have, traditionally, been, but not looking like a set of pouting, come-hither dominatrices.

Wenceslas Holler etched them in the seventeenth century (right) and they have re-emerged in modern day gaming ( though with a rather different, sexy, look which speaks to who it is who plays those games rather than any mythological authenticity ). Naked the furies may have, traditionally, been, but not looking like a set of pouting, come-hither dominatrices. The Pythia, or priestess of Apollo who spoke, as the Oracle, with Apollo’s voice is also a favourite subject in paint and in sculpture. Eugene Delacroix showed Lycurgus consulting her, John Collier made her a hooded, pre-raphaelite religious perched high on her tripod or three-legged stool (left). Note the gases swirling upwards from the crack in the floor of her underground room, the inhalation of which led to her madness and prophecies. No such crevice has been found at the Temple site, but, as a character explains in the book “geologists have found that two geological fault lines cross beneath Delphi, with fissures under the Temple itself which allow small amounts of naturally occurring gas to rise to the surface. Rock testing showed ethane, methane and ethylene − formerly used as an anaesthetic − to be present. These would create a calm, trancelike state and, if a lot was consumed, a form of wild mania.”

The Pythia, or priestess of Apollo who spoke, as the Oracle, with Apollo’s voice is also a favourite subject in paint and in sculpture. Eugene Delacroix showed Lycurgus consulting her, John Collier made her a hooded, pre-raphaelite religious perched high on her tripod or three-legged stool (left). Note the gases swirling upwards from the crack in the floor of her underground room, the inhalation of which led to her madness and prophecies. No such crevice has been found at the Temple site, but, as a character explains in the book “geologists have found that two geological fault lines cross beneath Delphi, with fissures under the Temple itself which allow small amounts of naturally occurring gas to rise to the surface. Rock testing showed ethane, methane and ethylene − formerly used as an anaesthetic − to be present. These would create a calm, trancelike state and, if a lot was consumed, a form of wild mania.” …and things are more familiar. The activity which accompanies publishing a crime fiction book was new to me with Plague, but this time, with Oracle, it’s less so. There are fewer decisions than last time because much has already been determined, Oracle will be consistent with Plague, in size, in print, in design. It even has approximately the same number of pages.

…and things are more familiar. The activity which accompanies publishing a crime fiction book was new to me with Plague, but this time, with Oracle, it’s less so. There are fewer decisions than last time because much has already been determined, Oracle will be consistent with Plague, in size, in print, in design. It even has approximately the same number of pages. these days such images come in various forms – Facebook banners, Instagram posts and Twitter headers – and some come with animation. The one on the right is an Instagram post, which uses a photograph of the Treasury of the Athenians at the Temple of Apollo, Delphi, as well as a copy of the cover and its tagline – ‘Blood calls for blood’ on a background of a full moon rising above a hillside. There is an animated version of this too.

these days such images come in various forms – Facebook banners, Instagram posts and Twitter headers – and some come with animation. The one on the right is an Instagram post, which uses a photograph of the Treasury of the Athenians at the Temple of Apollo, Delphi, as well as a copy of the cover and its tagline – ‘Blood calls for blood’ on a background of a full moon rising above a hillside. There is an animated version of this too. dramatic. I think it’s eye-catching. I just hope that the book isn’t mIstaken for a vampire novel (because of that tag-line). A number of early readers of Plague thought, from the blurb, that it was about a pandemic. No fear of misunderstanding the title this time, the blurb makes reference to the ancient oracle, but who knows what else people with think of.

dramatic. I think it’s eye-catching. I just hope that the book isn’t mIstaken for a vampire novel (because of that tag-line). A number of early readers of Plague thought, from the blurb, that it was about a pandemic. No fear of misunderstanding the title this time, the blurb makes reference to the ancient oracle, but who knows what else people with think of. There are some differences too, in part because I’ve learned from experience. So, for example, there’s an Oracle postcard to send out with review copies (last time I exhausted my personal stock of notelets). Claret is having the ARCs printed at the moment and I’ll be looking to take receipt of boxes of books in the next week or so. The other, more exciting thing is that readers are telling me that they’re waiting for the book to come out ( the virtue of having a series ). Also, it seems, there are a lot more media events – interviews, talks, blogs, podcasts – than last time. In part, I suspect because I have more media contacts now (and I’m good value i.e. or the most part, free), but also because I’m no longer an unknown. That Oracle is ‘the further adventures of…’ helps.

There are some differences too, in part because I’ve learned from experience. So, for example, there’s an Oracle postcard to send out with review copies (last time I exhausted my personal stock of notelets). Claret is having the ARCs printed at the moment and I’ll be looking to take receipt of boxes of books in the next week or so. The other, more exciting thing is that readers are telling me that they’re waiting for the book to come out ( the virtue of having a series ). Also, it seems, there are a lot more media events – interviews, talks, blogs, podcasts – than last time. In part, I suspect because I have more media contacts now (and I’m good value i.e. or the most part, free), but also because I’m no longer an unknown. That Oracle is ‘the further adventures of…’ helps.