Life is imitating art again. This time in regard to the, aptly named, ‘Oracle’. The second book in the series which ‘Plague’ began is set in Delphi, Greece and takes justice as its theme, in the way that the theme of ‘Plague’ is power. So it explores the idea of justice and how it is achieved, including concepts like vengeance, retribution, legal codes and punishment and law enforcement.

Life is imitating art again. This time in regard to the, aptly named, ‘Oracle’. The second book in the series which ‘Plague’ began is set in Delphi, Greece and takes justice as its theme, in the way that the theme of ‘Plague’ is power. So it explores the idea of justice and how it is achieved, including concepts like vengeance, retribution, legal codes and punishment and law enforcement.

This is particularly relevant in societies where the law, as a means of achieving justice for everyone, is becoming out of reach for many, thereby diluting justice for all. Either because of cost (and the vast reduction in legal aid available to those who don’t have the money to seek justice) or because of right wing populist, media-amplified ideas that people belonging to certain groups do not deserve access to justice. Asylum seekers, for example, or refugees. Demonising the ‘other’ is a standard populist tactic, so are attacks on the concept of human rights, which are, by their nature, applicable to all human  beings, regardless.

beings, regardless.

If this makes ‘Oracle’ sound dull, I would like to reassure you that it’s only as dull as ‘Plague’ was and a quick glance at reader reviews on Goodreads or Amazon, or its critical reception, shows that ‘Plague’ was pretty exciting.

I was prompted towards justice as a theme by recent events, particularly the Supreme Court preventing the executive from shutting down Parliament, the UK’s sovereign body. The ongoing Black Lives Matter protests at the treatment by the police of specific groups of people, those who happen not to be white, in the States and here also played a part. More recently the death of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader  Ginsberg and the scramble to replace her with someone partisan towards a specific political position also highlighted the link between justice and politics.

Ginsberg and the scramble to replace her with someone partisan towards a specific political position also highlighted the link between justice and politics.

In ‘Oracle’ a senior politician doesn’t trust that the officers being sent to investigate murky goings on are truly impartial, because of the politicisation of the police. In Greece there are close historic ties between the police and the military, which ruled the country as a junta until 1974. I began writing ‘Oracle’ in early 2019, however, some time before the legal trial of a whole political party, Golden Dawn.

On 7 October 2020, Athens Appeals Court ruled that Golden Dawn operated as a  criminal organization, systematically attacking migrants and leftists. The court also announced verdicts for sixty-eight defendants including the party’s political leadership. Nikolaos Michaloliakos and six other prominent members and former MPs, charged with running a criminal organization, were found guilty. Verdicts of murder, attempted murder, and violent attacks on immigrants and left-wing political opponents were also delivered. Golden Dawn held 17 seats in the Hellenic Parliament only five years ago. An independent investigation by the Council of Europe found disturbing links between Golden Dawn and the police.

criminal organization, systematically attacking migrants and leftists. The court also announced verdicts for sixty-eight defendants including the party’s political leadership. Nikolaos Michaloliakos and six other prominent members and former MPs, charged with running a criminal organization, were found guilty. Verdicts of murder, attempted murder, and violent attacks on immigrants and left-wing political opponents were also delivered. Golden Dawn held 17 seats in the Hellenic Parliament only five years ago. An independent investigation by the Council of Europe found disturbing links between Golden Dawn and the police.

The politicisation of elements of the justice system which already feature in ‘Oracle’ have a real life corollary. Just as elements of the governing system in ‘Plague’, like the awarding of large sums of taxpayers’ money to companies without any track record, or assets, avoiding due diligence and accountability, have a similar echo in real life. It’s encouraging and dis-spiriting at the same time.

If you’re interested in reading about the coincidences between the plot of Plague and real life try Plague – Stranger than Fiction The Plague Story Continues Stranger than Fiction II

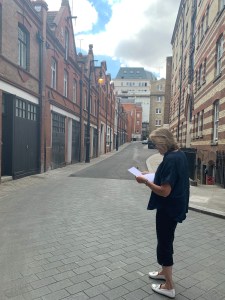

So, we’ve had the Plague Book walk and the Plague Blog Tour ( which finished on Friday ) and both have been fun to do and, I hope, brought the book to the attention of the book-buying public, or at least that section of it which exists on-line. This is the first time a book of mine has been part of a Blog Tour and it’s been an interesting and enjoyable experience. Emma from Damp Pebbles, a crime and horror specialist blog tour organiser, has been helpful and professional throughout, marshalling the book bloggers to produce and reveal their reviews day after day.

So, we’ve had the Plague Book walk and the Plague Blog Tour ( which finished on Friday ) and both have been fun to do and, I hope, brought the book to the attention of the book-buying public, or at least that section of it which exists on-line. This is the first time a book of mine has been part of a Blog Tour and it’s been an interesting and enjoyable experience. Emma from Damp Pebbles, a crime and horror specialist blog tour organiser, has been helpful and professional throughout, marshalling the book bloggers to produce and reveal their reviews day after day. reading what people made of it and there were some new insights too, which even this author hadn’t thought about. For example, thank you Karen Cole for pointing out just how often Cassie self-sabotages. There is also some anticipation around Oracle, the next in the series ( many of the bloggers said they would like to review that one as well ).

reading what people made of it and there were some new insights too, which even this author hadn’t thought about. For example, thank you Karen Cole for pointing out just how often Cassie self-sabotages. There is also some anticipation around Oracle, the next in the series ( many of the bloggers said they would like to review that one as well ). In the absence of a physical launch and book shop signings, I’ve spoken about the book and the writing of it on radio and Youtube ( you can hear/see those interviews and events, if you’ve a mind to, on the Events page of this web-site ). There is more of this planned, with recordings and uploading to Youtube ( to both the Claret Press channel and my own ). For example, at some point before Christmas there will be a discussion with various experts on London and its history.

In the absence of a physical launch and book shop signings, I’ve spoken about the book and the writing of it on radio and Youtube ( you can hear/see those interviews and events, if you’ve a mind to, on the Events page of this web-site ). There is more of this planned, with recordings and uploading to Youtube ( to both the Claret Press channel and my own ). For example, at some point before Christmas there will be a discussion with various experts on London and its history. sure how many members of the public would pay to come on either ( David, a London Walks specialist, thinks there may be people who would ). I have other events, interviews and talks, lined up and another twitter ‘giveaway’ too at the end of October.

sure how many members of the public would pay to come on either ( David, a London Walks specialist, thinks there may be people who would ). I have other events, interviews and talks, lined up and another twitter ‘giveaway’ too at the end of October. USA too.

USA too. One area which features in Plague but which was not covered by our recent bookwalk is SW4, or Clapham, where I happen to live. It is here that the heroine, Cassandra Fortune, has her flat, where she lives with her cat, Spiggott. Like so much of Clapham this would have been built by Victorian and Edwardian pattern builders, so named because they used a template, or several, when constructing street after street during the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. I have placed the flat in a fictitious road within the little maze of roads off Clapham Common South Side, where the buildings are often elegant purpose built maisonettes.

One area which features in Plague but which was not covered by our recent bookwalk is SW4, or Clapham, where I happen to live. It is here that the heroine, Cassandra Fortune, has her flat, where she lives with her cat, Spiggott. Like so much of Clapham this would have been built by Victorian and Edwardian pattern builders, so named because they used a template, or several, when constructing street after street during the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. I have placed the flat in a fictitious road within the little maze of roads off Clapham Common South Side, where the buildings are often elegant purpose built maisonettes.

Another of the aforementioned good things is Clapham Common, which sits in the middle of the Clapham area. It is a photograph of the Common and the ferris wheel of a travelling circus encamped there which alerts Cassie to a newspaper photographer having been snooping around. The photograph left was taken on 1st October 2020.

Another of the aforementioned good things is Clapham Common, which sits in the middle of the Clapham area. It is a photograph of the Common and the ferris wheel of a travelling circus encamped there which alerts Cassie to a newspaper photographer having been snooping around. The photograph left was taken on 1st October 2020. South and Clapham North (and we have the Junction too, we’re well connected – this is beginning to sound like an advert for Clapham). At each of them are circular, pillbox style structures which mark the presence of the deep shelters, constructed during the second World War to house civilians during air raids. There were originally ten of these planned across London, though only eight were ever sunk, three of them in Clapham close to the Northern line. Cassie notes the one next to Clapham Common tube station as Daljit, Sergeant Patel, drives her to the Golden Square crime scene. The image above is of the deep shelter at Clapham South, which was used, in the 1950s, to house those migrants arriving from Empire on the HMS Windrush and other similar, later, ships.

South and Clapham North (and we have the Junction too, we’re well connected – this is beginning to sound like an advert for Clapham). At each of them are circular, pillbox style structures which mark the presence of the deep shelters, constructed during the second World War to house civilians during air raids. There were originally ten of these planned across London, though only eight were ever sunk, three of them in Clapham close to the Northern line. Cassie notes the one next to Clapham Common tube station as Daljit, Sergeant Patel, drives her to the Golden Square crime scene. The image above is of the deep shelter at Clapham South, which was used, in the 1950s, to house those migrants arriving from Empire on the HMS Windrush and other similar, later, ships.

First a Book Walk for Plague, now a Book Tour!

First a Book Walk for Plague, now a Book Tour! COVID ( ironic for a book entitled ‘Plague’ ). As my previous post,

COVID ( ironic for a book entitled ‘Plague’ ). As my previous post,  First, they decide that no book should be stored in these over-crowded warehouse for more than 48 hours, so only the quick sellers will find house room ( a tough, if logical, commercial decision ). Second, Amazon turn to their tried and trusted method of making decisions about products – an algorithm. The algorithm is predictive and it determines which books are likely to sell quickly i.e. for which there is greatest demand.

First, they decide that no book should be stored in these over-crowded warehouse for more than 48 hours, so only the quick sellers will find house room ( a tough, if logical, commercial decision ). Second, Amazon turn to their tried and trusted method of making decisions about products – an algorithm. The algorithm is predictive and it determines which books are likely to sell quickly i.e. for which there is greatest demand. publisher, Claret Press, is a small indie, which doesn’t have the budget for a massive sales pitch and stormtrooper publicists and this counts against Plague too. The clever algorithm is never going to choose to stock Plague over many of those other books. So ‘Temporarily Out of Stock’ appears, even though the book is available.

publisher, Claret Press, is a small indie, which doesn’t have the budget for a massive sales pitch and stormtrooper publicists and this counts against Plague too. The clever algorithm is never going to choose to stock Plague over many of those other books. So ‘Temporarily Out of Stock’ appears, even though the book is available. however hard I, and Claret Press, work, it’s unlikely to impress that algorithm.

however hard I, and Claret Press, work, it’s unlikely to impress that algorithm. Yes, it’s happening today, 15th September! And I’m getting some excellent feedback and reviews! So pleased, after all the hard work.

Yes, it’s happening today, 15th September! And I’m getting some excellent feedback and reviews! So pleased, after all the hard work. taking place now I would have to do a major rewrite to incorporate COVID and some, at least, of the events of the novel almost certainly wouldn’t take place. Given that the editing phase of the book was concluded in April, when we had just entered lock down and no one knew what was going to happen, this wasn’t an option. Hence the removal of the year.

taking place now I would have to do a major rewrite to incorporate COVID and some, at least, of the events of the novel almost certainly wouldn’t take place. Given that the editing phase of the book was concluded in April, when we had just entered lock down and no one knew what was going to happen, this wasn’t an option. Hence the removal of the year. This year they returned on 1st September but will not close as usual. Like all physical gatherings, even relatively small ones (the ‘rule of six’) the conferences have been cancelled and activity will take place online. Given the imminent shenanigans in the Palace of Westminster in regard to the UK Internal Markets Bill, they may not take place at all. The current Parliamentary schedule currently shows PMQs and Private Members Bills proceeding throughout October, but little else.

This year they returned on 1st September but will not close as usual. Like all physical gatherings, even relatively small ones (the ‘rule of six’) the conferences have been cancelled and activity will take place online. Given the imminent shenanigans in the Palace of Westminster in regard to the UK Internal Markets Bill, they may not take place at all. The current Parliamentary schedule currently shows PMQs and Private Members Bills proceeding throughout October, but little else. (and major works) which sets the time limit for solving the case. The first arrest is made for a crime committed on 10th September and the day – and night – of 15th has a particular significance (early readers of the book will know this). Hence the publication date of 15th September.

(and major works) which sets the time limit for solving the case. The first arrest is made for a crime committed on 10th September and the day – and night – of 15th has a particular significance (early readers of the book will know this). Hence the publication date of 15th September. First up – bricks. The Victorians were great decorators in brick, something I’ve had several conversations about recently because we’ve just had a face lift for our Victorian house. I now know more about bricks than I ever thought was possible, largely courtesy of David Fairbrother, who oversaw the work, a man who truly loves bricks. On our walk we encountered some excellent examples of Victorian brickwork, like that announcing Grosvenor Works or the decoration on the buildings at the top of Great Smith Street, or, see left, the brickwork on the Marlborough Head public house, North Audley Street (readers of the novel will recognise that street name). The young woman working there was surprised and, I think, rather charmed, by our fruitless search

First up – bricks. The Victorians were great decorators in brick, something I’ve had several conversations about recently because we’ve just had a face lift for our Victorian house. I now know more about bricks than I ever thought was possible, largely courtesy of David Fairbrother, who oversaw the work, a man who truly loves bricks. On our walk we encountered some excellent examples of Victorian brickwork, like that announcing Grosvenor Works or the decoration on the buildings at the top of Great Smith Street, or, see left, the brickwork on the Marlborough Head public house, North Audley Street (readers of the novel will recognise that street name). The young woman working there was surprised and, I think, rather charmed, by our fruitless search  for any indicator that there were Roman baths nearby.

for any indicator that there were Roman baths nearby. broadly, around the subject matter of the book. So, a Stop Works sign propped in a doorway of the Norman Shaw buildings on the Embankment ( a former home of the Metropolitan Police and work place of one of the victims in the novel, where he is helping to refurbish the building ). Colourful chains at the construction site on Davies Street by Bond Street Underground Station, site of the first discovered crime, against said victim. The vaulted roof of the arches through which one passes from Horseguards Parade into Whitehall (which appears to be numbered, something I’ve not noticed before) and the receding arches within the arches, through which the protesters pass before harassing my heroine.

broadly, around the subject matter of the book. So, a Stop Works sign propped in a doorway of the Norman Shaw buildings on the Embankment ( a former home of the Metropolitan Police and work place of one of the victims in the novel, where he is helping to refurbish the building ). Colourful chains at the construction site on Davies Street by Bond Street Underground Station, site of the first discovered crime, against said victim. The vaulted roof of the arches through which one passes from Horseguards Parade into Whitehall (which appears to be numbered, something I’ve not noticed before) and the receding arches within the arches, through which the protesters pass before harassing my heroine. houses in London. Not, perhaps the smallest that, I believe, is The Dove in Hammersmith, but pretty small nonetheless. We found the four-storey Coach and Horses on the edge of Mayfair, it is still a working pub ( though we didn’t enter, either this or the Marlborough Head, just in case you’re wondering, we were committed book walkers ). Besides, the No Entry sign outside could have put us off. Other unusual architecture spotted includes Sothebys’ warehouse, found down a back street and what looked like a closed up market hall in Davies Mews.

houses in London. Not, perhaps the smallest that, I believe, is The Dove in Hammersmith, but pretty small nonetheless. We found the four-storey Coach and Horses on the edge of Mayfair, it is still a working pub ( though we didn’t enter, either this or the Marlborough Head, just in case you’re wondering, we were committed book walkers ). Besides, the No Entry sign outside could have put us off. Other unusual architecture spotted includes Sothebys’ warehouse, found down a back street and what looked like a closed up market hall in Davies Mews. There is the recent, real, discovery of hundreds of bodies, skeletons, in a lost medieval sacristy belonging to Westminster Abbey as reported in

There is the recent, real, discovery of hundreds of bodies, skeletons, in a lost medieval sacristy belonging to Westminster Abbey as reported in  be what I can only call the procurement scandals. In the novel large government contracts, worth several billion pounds, are being tendered and, as one of the characters says ‘…the contracts aren’t being awarded in the usual way.’ It’s corruption – the contracts are being given to companies run by associates and accomplices of the villains, who also make money on the stock exchange as the shares of those companies rise in value. At least in the book the companies in question have the relevant expertise and a track record in providing the types of services being tendered for.

be what I can only call the procurement scandals. In the novel large government contracts, worth several billion pounds, are being tendered and, as one of the characters says ‘…the contracts aren’t being awarded in the usual way.’ It’s corruption – the contracts are being given to companies run by associates and accomplices of the villains, who also make money on the stock exchange as the shares of those companies rise in value. At least in the book the companies in question have the relevant expertise and a track record in providing the types of services being tendered for. three companies, one specialising in pest control, one a confectionery wholesaler and one an opaque private fund owned via a tax haven. The PPE – face masks – sold by the last of these companies, Ayanda Capital, under a contract worth £252m, was found to be unsuitable for use in the NHS (and untested). Yet at least this contract was publicly tendered. The contracts granted to Public First, a company with close ties to Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings, seem not to have been tendered at all and The Good Law Project and a number of non-Tory MPs are seeking judicial review of the awarding of them. They have also begun proceedings against Michael Gove in regard to one of these contracts. Contrary to government regulations, the contracts themselves have not been published (once granted, contracts are required to be published within thirty days).

three companies, one specialising in pest control, one a confectionery wholesaler and one an opaque private fund owned via a tax haven. The PPE – face masks – sold by the last of these companies, Ayanda Capital, under a contract worth £252m, was found to be unsuitable for use in the NHS (and untested). Yet at least this contract was publicly tendered. The contracts granted to Public First, a company with close ties to Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings, seem not to have been tendered at all and The Good Law Project and a number of non-Tory MPs are seeking judicial review of the awarding of them. They have also begun proceedings against Michael Gove in regard to one of these contracts. Contrary to government regulations, the contracts themselves have not been published (once granted, contracts are required to be published within thirty days). money involved.’ My main character Cassie is, of course, working on minor procurement contracts at the start of the novel, but she has no enthusiasm for the work. As a former senior civil servant I sympathise with those who are having to deal with the situation now, knowing that the correct procedures aren’t being followed. It seems that Ministers are hiding behind COVID and emergency powers to hand large sums of money to preferred bidders, regardless of said bidders ability to deliver the contracts.

money involved.’ My main character Cassie is, of course, working on minor procurement contracts at the start of the novel, but she has no enthusiasm for the work. As a former senior civil servant I sympathise with those who are having to deal with the situation now, knowing that the correct procedures aren’t being followed. It seems that Ministers are hiding behind COVID and emergency powers to hand large sums of money to preferred bidders, regardless of said bidders ability to deliver the contracts. Now that publication day for ‘Plague’ approaches (just under three weeks to go ) it seems an appropriate time to recap on how the book got where it is. I began writing it in 2018 at the behest of Claret Press, a small independent publishers. This took just over a year and a half. When re-writing and revising I engaged with a number of book clubs around the country as well as with members of the writer’s group to which I belong in south London, to take their views. In addition, as part of my research, I have consulted a number of experts – a micro-biologist, a retired policeman and several people who work, or worked, in the Palace of Westminster.

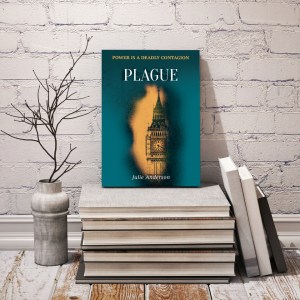

Now that publication day for ‘Plague’ approaches (just under three weeks to go ) it seems an appropriate time to recap on how the book got where it is. I began writing it in 2018 at the behest of Claret Press, a small independent publishers. This took just over a year and a half. When re-writing and revising I engaged with a number of book clubs around the country as well as with members of the writer’s group to which I belong in south London, to take their views. In addition, as part of my research, I have consulted a number of experts – a micro-biologist, a retired policeman and several people who work, or worked, in the Palace of Westminster.

A number of reviewers read the blurb, looked at the cover and downloaded the text clearly expecting something other than what’s in my book. Their expectations centred on it being a ‘government conspiracy’ novel, possibly in regard to some form of bio-weapon (hence ‘Plague’). I don’t know how that expectation was raised, but it clearly was for a number of people and that had to be addressed. I want to sell books, but I don’t want to disappoint readers, which will happen if they buy it thinking it is something other than it actually is.

A number of reviewers read the blurb, looked at the cover and downloaded the text clearly expecting something other than what’s in my book. Their expectations centred on it being a ‘government conspiracy’ novel, possibly in regard to some form of bio-weapon (hence ‘Plague’). I don’t know how that expectation was raised, but it clearly was for a number of people and that had to be addressed. I want to sell books, but I don’t want to disappoint readers, which will happen if they buy it thinking it is something other than it actually is. Is the thought of my heroine, Cassie, when told where another character in my novel lives. Yet, before our Bookwalk took us to look at the enviable address, we had some more medieval ground to cover, specifically the 14th century Jewel Tower. This remnant of the Abbey, which stood next to the Abbey moat, now stands on Abingdon or ‘College’ Green opposite Parliament. It is part of the Palace of Westminster, although set apart from Barry’s Victorian pile and Westminster Hall and it plays a crucial role in Plague.

Is the thought of my heroine, Cassie, when told where another character in my novel lives. Yet, before our Bookwalk took us to look at the enviable address, we had some more medieval ground to cover, specifically the 14th century Jewel Tower. This remnant of the Abbey, which stood next to the Abbey moat, now stands on Abingdon or ‘College’ Green opposite Parliament. It is part of the Palace of Westminster, although set apart from Barry’s Victorian pile and Westminster Hall and it plays a crucial role in Plague. ground which surrounds it, a testament to its great age. It is open to the public, though not at the present moment. We entertained a rather bored-looking set of professional camera men set up in their familiar interviewing place on the Green, by doing our own ‘pieces to camera’ both in front of the Jewel Tower and the Victoria Tower, one of the few parts of the Palace of Westminster not covered in scaffolding or sheeting. Returning to Parliament Square, we went past the Abbey itself and entered Great Smith Street, then Little Smith Street, into that maze of small alleyways with buildings belonging to the Abbey and the Church.

ground which surrounds it, a testament to its great age. It is open to the public, though not at the present moment. We entertained a rather bored-looking set of professional camera men set up in their familiar interviewing place on the Green, by doing our own ‘pieces to camera’ both in front of the Jewel Tower and the Victoria Tower, one of the few parts of the Palace of Westminster not covered in scaffolding or sheeting. Returning to Parliament Square, we went past the Abbey itself and entered Great Smith Street, then Little Smith Street, into that maze of small alleyways with buildings belonging to the Abbey and the Church. Great College Street was our destination, where Westminster School buildings run into the 14th century boundary wall, and under which the River Tyburn ran. It is on the corner with Barton Street where our desirable residence sits. Here we were fortunate to come across a woman who worked in the next house along, who was charmed by the thought of the neighbouring house appearing in a novel (and we think we made a sale). I hope the occupants of the actual house are equally charmed.

Great College Street was our destination, where Westminster School buildings run into the 14th century boundary wall, and under which the River Tyburn ran. It is on the corner with Barton Street where our desirable residence sits. Here we were fortunate to come across a woman who worked in the next house along, who was charmed by the thought of the neighbouring house appearing in a novel (and we think we made a sale). I hope the occupants of the actual house are equally charmed. Smith Square, are, to my mind, some of the most desirable in London. The fine Georgian town houses sit in quiet, tree-lined streets, yet are close to one of London’s ‘centres’ and the epicentre of establishment power. Many of them are still in private ownership, either as houses or apartments, though there are many school buildings at the north end and the Georgian buildings give way to corporate headquarters and government departments to the south. Marsham Street is lined with government

Smith Square, are, to my mind, some of the most desirable in London. The fine Georgian town houses sit in quiet, tree-lined streets, yet are close to one of London’s ‘centres’ and the epicentre of establishment power. Many of them are still in private ownership, either as houses or apartments, though there are many school buildings at the north end and the Georgian buildings give way to corporate headquarters and government departments to the south. Marsham Street is lined with government  buildings – the Home Office, the Department for Transport, the old DTI building, many of them linked. All lie on the route of the number 88 bus – the ‘Clapham omnibus’ – and we hopped on to it for a few stops to Pimlico, because we were running out of time (and, by now, our feet were hurting). The Pimlico which we currently see, of elegant early Victorian terraces, is predominantly the creation of the property developer Thomas Cubitt in the 1830s. In the novel it is where a

buildings – the Home Office, the Department for Transport, the old DTI building, many of them linked. All lie on the route of the number 88 bus – the ‘Clapham omnibus’ – and we hopped on to it for a few stops to Pimlico, because we were running out of time (and, by now, our feet were hurting). The Pimlico which we currently see, of elegant early Victorian terraces, is predominantly the creation of the property developer Thomas Cubitt in the 1830s. In the novel it is where a  supporting character lives, on Tachbrook Street, so named for the Tach Brook which, at this point, ran into the old River Tyburn and thence to the Thames.

supporting character lives, on Tachbrook Street, so named for the Tach Brook which, at this point, ran into the old River Tyburn and thence to the Thames. halves awaited. The day ended with a most perfect sunset over the Thames and Pimlico. A really great walk ( over seven miles of it ) and a really great day. My thanks to Helen Hughes for her photography and her company.

halves awaited. The day ended with a most perfect sunset over the Thames and Pimlico. A really great walk ( over seven miles of it ) and a really great day. My thanks to Helen Hughes for her photography and her company.