Yesterday I went to the British Museum to catch the Peru exhibition before it closes on 20th February. This relatively small but very interesting exhibition is in the Great Court Gallery (above the Reading Room) and is organised in conjunction with the Museo de Arte de Lima. It brings together artefacts from the BM’s own collection with those from Peru and elsewhere to reveal the history, beliefs and culture of a series of South American societies and peoples from BCE to the sixteenth century arrival of the conquistadors.

Yesterday I went to the British Museum to catch the Peru exhibition before it closes on 20th February. This relatively small but very interesting exhibition is in the Great Court Gallery (above the Reading Room) and is organised in conjunction with the Museo de Arte de Lima. It brings together artefacts from the BM’s own collection with those from Peru and elsewhere to reveal the history, beliefs and culture of a series of South American societies and peoples from BCE to the sixteenth century arrival of the conquistadors.

My knowledge of such societies was restricted to Schaffer’s 1964 play The Royal Hunt of the Sun, numerous bloodthirsty films and cartoons from childhood, the wonderful Royal Academy exhibition of the 90s on the Aztecs (from a different part of south America completely) and, perhaps most personally, the Palacio del Conde de los Andes in Jerez de la Frontera, which belonged to the last Viceroy of Peru. This exhibition has expanded it enormously, covering as it does the period between 2500 BCE and the 1500s, tropical forests, arid plains and, above all, the Andes, a geographical region centred on Peru, but including Argentina, Bolivia, Columbia and Ecuador. I was completely ignorant of the people who lived at Chavin de Huantar (1200BCE) who made the remarkable gold headdress and earrings (right). Theirs was a site of pilgrimage to an oracle. In southern Peru archeologists discovered the funerary goods of the Paracas people (900BCE) who were followed by the more famous Nascas (200BCE-600CE) with their amazing and huge geoglyphs, which can only be seen in their entirety from the sky.

perhaps most personally, the Palacio del Conde de los Andes in Jerez de la Frontera, which belonged to the last Viceroy of Peru. This exhibition has expanded it enormously, covering as it does the period between 2500 BCE and the 1500s, tropical forests, arid plains and, above all, the Andes, a geographical region centred on Peru, but including Argentina, Bolivia, Columbia and Ecuador. I was completely ignorant of the people who lived at Chavin de Huantar (1200BCE) who made the remarkable gold headdress and earrings (right). Theirs was a site of pilgrimage to an oracle. In southern Peru archeologists discovered the funerary goods of the Paracas people (900BCE) who were followed by the more famous Nascas (200BCE-600CE) with their amazing and huge geoglyphs, which can only be seen in their entirety from the sky.

In northern Peru the Moche people (100-800 CE), fabulous ceramicists (see figure of a Moche warrior, left), concentrated along the coasts and river valleys, while the Wari (600-900CE) developed in the Ayacucho region and expanded to cover the southern highlands and the northern coast. Then, between the 10th and 12th centuries the Kingdom of Chimu dominated, its capital Chan Chan having a population of up to 75,000 people. In the central Andes the Inca empire emerged in about 1400, expanding its territory throughout the region, via a system of roads and waterways between diverse cultures and communities. This included the creation of the mountain fastness which is Machu Pichu, or ‘ancient mountain’, including about 200 polished stone buildings, as well as terraces and pyramids. Though this was not the Inca capital, which was at Cusco.

In northern Peru the Moche people (100-800 CE), fabulous ceramicists (see figure of a Moche warrior, left), concentrated along the coasts and river valleys, while the Wari (600-900CE) developed in the Ayacucho region and expanded to cover the southern highlands and the northern coast. Then, between the 10th and 12th centuries the Kingdom of Chimu dominated, its capital Chan Chan having a population of up to 75,000 people. In the central Andes the Inca empire emerged in about 1400, expanding its territory throughout the region, via a system of roads and waterways between diverse cultures and communities. This included the creation of the mountain fastness which is Machu Pichu, or ‘ancient mountain’, including about 200 polished stone buildings, as well as terraces and pyramids. Though this was not the Inca capital, which was at Cusco.

The Incas were eventually deposed by the Spanish, led by Pizarro and a brutal repression of indigenous ways of life followed. It is Pizarro’s first encounter and subsequent relationship with the Inca Emperor Atahuallpa which features in the aforementioned play (and film). The exhibition included artefacts from the colonial period, though not many of them.

ways of life followed. It is Pizarro’s first encounter and subsequent relationship with the Inca Emperor Atahuallpa which features in the aforementioned play (and film). The exhibition included artefacts from the colonial period, though not many of them.

What I found fascinating about the peoples living in these regions was that they developed art and technology (the roads and waterways across the Andes for example) without a system of writing. Rather they used a system of khipu to transmit information – knotted textiles. I imagine that they also had an oral tradition of storytelling, most ancient societies did, but, because these stories were never written down these would have been lost.  They certainly had complex belief systems, centred on nature and the land, as shown by the exquisite ceramics in the form of felines and serpents (see left). It also included blood sacrifice (back to those childhood bloodthirsty yarns) with any prisoners captured during wars being slain as a sacrifice to the gods of the land. One funerary robe included no fewer than seventy four human figures in its border and central pattern, each of them carrying a severed human head. Ceramics and musical instruments were decorated with similarly gruesome patterns. The exhibition includes a number of sculptures of captured prisoners, roped and awaiting their fate.

They certainly had complex belief systems, centred on nature and the land, as shown by the exquisite ceramics in the form of felines and serpents (see left). It also included blood sacrifice (back to those childhood bloodthirsty yarns) with any prisoners captured during wars being slain as a sacrifice to the gods of the land. One funerary robe included no fewer than seventy four human figures in its border and central pattern, each of them carrying a severed human head. Ceramics and musical instruments were decorated with similarly gruesome patterns. The exhibition includes a number of sculptures of captured prisoners, roped and awaiting their fate.

If you get the opportunity, do visit this exhibition before it closes. It isn’t huge, but leave yourself plenty of time, there’s a lot to absorb. Entry costs £17, with some £14.80 concessions.

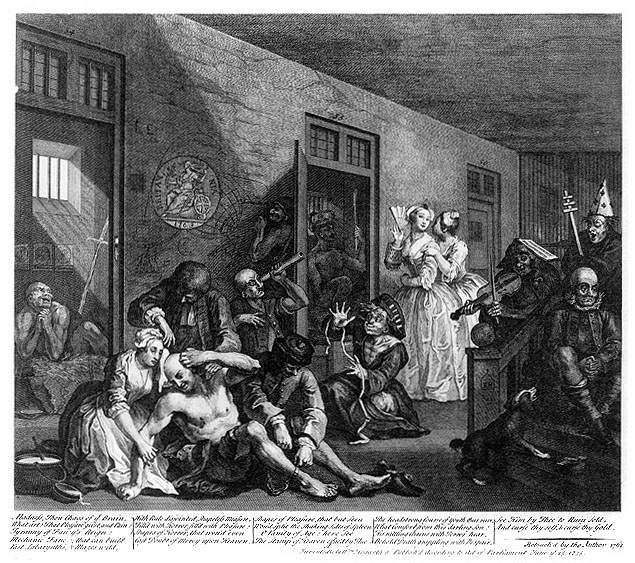

One of Tate Britain’s big shows this winter, Hogarth and Europe looks at the ever popular eighteenth century artist in the context of the changing society of the time and the similarities with artists across Europe. I went to take a look last week.

One of Tate Britain’s big shows this winter, Hogarth and Europe looks at the ever popular eighteenth century artist in the context of the changing society of the time and the similarities with artists across Europe. I went to take a look last week. were striking, the family resemblance between then and with their brother very evident. That said, there is always more to be found in his very full frames and this exhibition draws attention to particular aspects not focused on before.

were striking, the family resemblance between then and with their brother very evident. That said, there is always more to be found in his very full frames and this exhibition draws attention to particular aspects not focused on before. The exhibition prompts you to look at the familiar scenes with a social historian’s eye, picking out that fine, oriental china cluttering the Squanderfield’s mantlepiece, noticing the French furnishings, the French and Dutch old masters on the wall in The Marriage Settlement, the exotics – the black slaves, the Italian castrato singer, the French dancing master – in later Marriage paintings. Whilst seeing his black characters, usually unfree, I hadn’t noticed before the way that Hogarth often positions them (not just household slaves, but in street scenes too) as a counter to white immorality.

The exhibition prompts you to look at the familiar scenes with a social historian’s eye, picking out that fine, oriental china cluttering the Squanderfield’s mantlepiece, noticing the French furnishings, the French and Dutch old masters on the wall in The Marriage Settlement, the exotics – the black slaves, the Italian castrato singer, the French dancing master – in later Marriage paintings. Whilst seeing his black characters, usually unfree, I hadn’t noticed before the way that Hogarth often positions them (not just household slaves, but in street scenes too) as a counter to white immorality.  unfunny, though chock-full of detail, but I acknowledge its originality and influence. He was very famous during his lifetime mainly because so many of his ‘morality’ works were turned into prints (he studied, originally as an engraver). He has also been a major influence on later artists and the word ‘Hogarthian’ has come to represent many a teeming, rambunctious and satiric scene. This exhibition shows that, while his European contemporaries were painting scenes of the city, like him, they were far less assured in their social commentary and much less irreverent and satirical. Some, like Canaletto, were content to capture (very beautifully, it must be said) what was before them.

unfunny, though chock-full of detail, but I acknowledge its originality and influence. He was very famous during his lifetime mainly because so many of his ‘morality’ works were turned into prints (he studied, originally as an engraver). He has also been a major influence on later artists and the word ‘Hogarthian’ has come to represent many a teeming, rambunctious and satiric scene. This exhibition shows that, while his European contemporaries were painting scenes of the city, like him, they were far less assured in their social commentary and much less irreverent and satirical. Some, like Canaletto, were content to capture (very beautifully, it must be said) what was before them. I appreciated the charitable work he did, with other artists and musicians, notably Handel, in supporting the Foundlings Hospital but I hadn’t understood that his preoccupation with the materialism and moral decline of ‘modern’ society was also fueled by his own history. His father got into debt and was imprisoned for a time, leaving the young Hogarth and his mother to provide for the family. The Madhouse final scene from Rake was only a metaphorical step away from the debtor’s prison where Hogarth senior had been incarcerated.

I appreciated the charitable work he did, with other artists and musicians, notably Handel, in supporting the Foundlings Hospital but I hadn’t understood that his preoccupation with the materialism and moral decline of ‘modern’ society was also fueled by his own history. His father got into debt and was imprisoned for a time, leaving the young Hogarth and his mother to provide for the family. The Madhouse final scene from Rake was only a metaphorical step away from the debtor’s prison where Hogarth senior had been incarcerated. week I returned there for a second exhibition of Hokusai work, this time focusing on his drawings for The Great Picture Book of Everything.

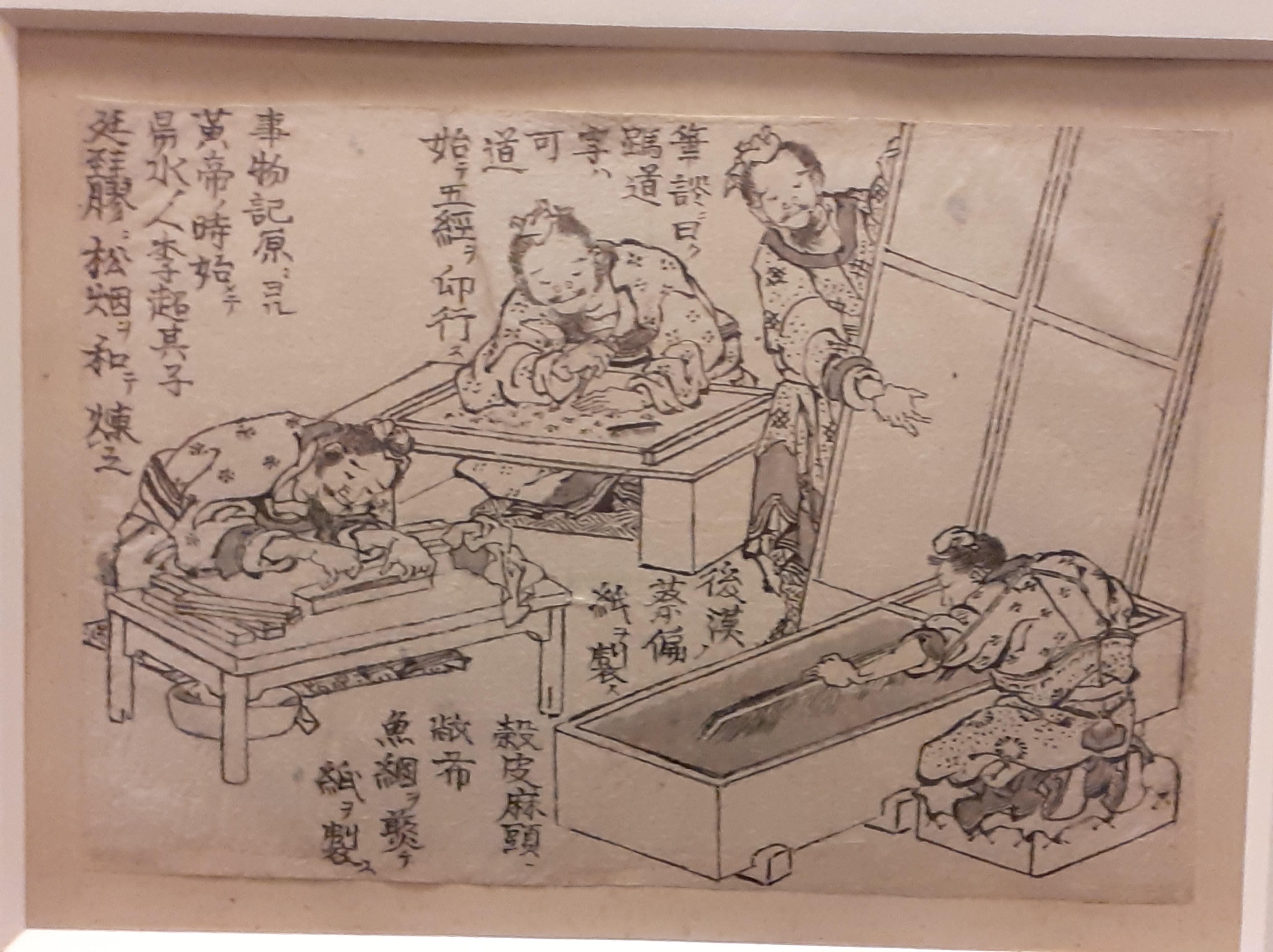

week I returned there for a second exhibition of Hokusai work, this time focusing on his drawings for The Great Picture Book of Everything. As an example of the production process there is a section on the print known as The Great Wave, for which Hokusai is probably most famous. There are many thousands of versions of this picture, called Under the Wave off Kanagawa ( first published 1831 ). Woodblock prints were inexpensive in nineteenth century Japan, costing approximately the same as two dishes of noodles and the blocks would be used to produce thousands of images. They frequently wore down, creating different versions of the same image and when new blocks were created, these too could differ from the original.

As an example of the production process there is a section on the print known as The Great Wave, for which Hokusai is probably most famous. There are many thousands of versions of this picture, called Under the Wave off Kanagawa ( first published 1831 ). Woodblock prints were inexpensive in nineteenth century Japan, costing approximately the same as two dishes of noodles and the blocks would be used to produce thousands of images. They frequently wore down, creating different versions of the same image and when new blocks were created, these too could differ from the original. their subjects. They are also remarkable for their subject matter. Between 1639 and 1859 Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa shoguns who forbade the Japanese people from travelling abroad. Yet in producing the drawings, between 1820 and 1860, Hokusai depicted peoples from foreign lands as well as characters from Indian and Chinese mythology ( see right, figures of India, China and Korea ).

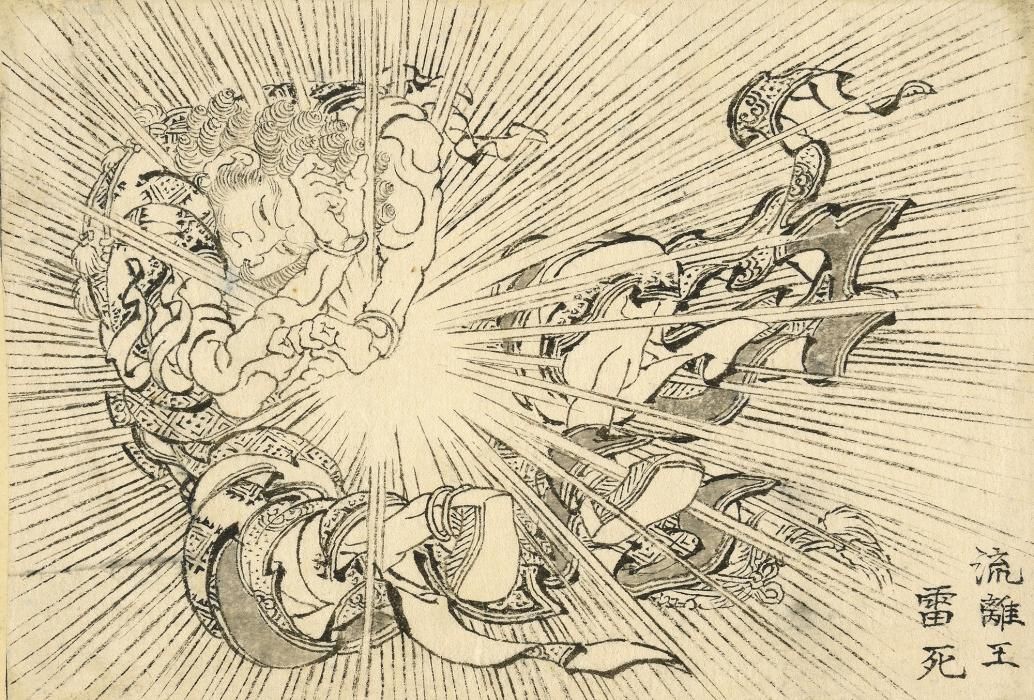

their subjects. They are also remarkable for their subject matter. Between 1639 and 1859 Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa shoguns who forbade the Japanese people from travelling abroad. Yet in producing the drawings, between 1820 and 1860, Hokusai depicted peoples from foreign lands as well as characters from Indian and Chinese mythology ( see right, figures of India, China and Korea ). That said, I realised early in my visit that I would have to buy the catalogue, because it simply isn’t possible to stand for long enough in front of these small pictures to really enjoy all their detail and subtlety – too many other people are trying to do the same. Besides, it’s a book and I can’t resist book buying. The exhibition is in Room 90, one of the rooms used for small exhibitions of prints and drawings at the rear of the Museum ( beyond Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt and up the stairs ). Entry is only £9 for adults and, even with timed tickets, it was getting crowded when I visited.

That said, I realised early in my visit that I would have to buy the catalogue, because it simply isn’t possible to stand for long enough in front of these small pictures to really enjoy all their detail and subtlety – too many other people are trying to do the same. Besides, it’s a book and I can’t resist book buying. The exhibition is in Room 90, one of the rooms used for small exhibitions of prints and drawings at the rear of the Museum ( beyond Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt and up the stairs ). Entry is only £9 for adults and, even with timed tickets, it was getting crowded when I visited. have come from the pages of a modern comic/graphic novel or a Roy Lichtenstein work ( Kerpow! ). All they would need would be primary colours. Others depict interior scenes or verandas in a way which reminded me of Degas, with an asymmetrical picture construction. I look forward to many happy hours with my catalogue, really appreciating these drawings in full detail, but, as an enticing taster, this exhibition was wonderful. It runs until 30th January 2022 and the book costs £20.

have come from the pages of a modern comic/graphic novel or a Roy Lichtenstein work ( Kerpow! ). All they would need would be primary colours. Others depict interior scenes or verandas in a way which reminded me of Degas, with an asymmetrical picture construction. I look forward to many happy hours with my catalogue, really appreciating these drawings in full detail, but, as an enticing taster, this exhibition was wonderful. It runs until 30th January 2022 and the book costs £20. On a grey and somewhat chilly Bank Holiday Sunday English National Opera, with the full ENO orchestra and chorus and soloists David Junghoon Kim, Natalya Romaniw and Roland Wood were at Crystal Palace Park. So were we.

On a grey and somewhat chilly Bank Holiday Sunday English National Opera, with the full ENO orchestra and chorus and soloists David Junghoon Kim, Natalya Romaniw and Roland Wood were at Crystal Palace Park. So were we. couple of burger joints, a pizza place, churros and sushi – with long queues, which meant people walking back to their places bearing food after the performance had commenced. There were bars aplenty, unfortunately they sold only hugely overpriced cans – of beer, of wine and of gin & tonic. No draught beer, no bottles of wine. And no bringing your own drinks with you. We knew this, so didn’t try, but others clearly did not and had their goodies confiscated at the entrance. Given the lack of choice and the prices charged this left a sour taste in a lot of mouths.

couple of burger joints, a pizza place, churros and sushi – with long queues, which meant people walking back to their places bearing food after the performance had commenced. There were bars aplenty, unfortunately they sold only hugely overpriced cans – of beer, of wine and of gin & tonic. No draught beer, no bottles of wine. And no bringing your own drinks with you. We knew this, so didn’t try, but others clearly did not and had their goodies confiscated at the entrance. Given the lack of choice and the prices charged this left a sour taste in a lot of mouths. the back of Zone A, only a few yards from where we sat. They weren’t pleased and understandably so.

the back of Zone A, only a few yards from where we sat. They weren’t pleased and understandably so. and powerful Cavaradossi who reached those high notes with ease. Romaniw was empassioned and exquisite – even in a park and with an audience this big, you could have heard a pin drop during ‘Vissi d’arte‘. At the end, everyone was on their feet and clapping and cheering ( and booing Scarpia, who was an excellent Roland Wood ). Though there were also folk beginning to clear away their things – it was cold by this time. The group to the immediate right of us had brought duvets, they were snug.

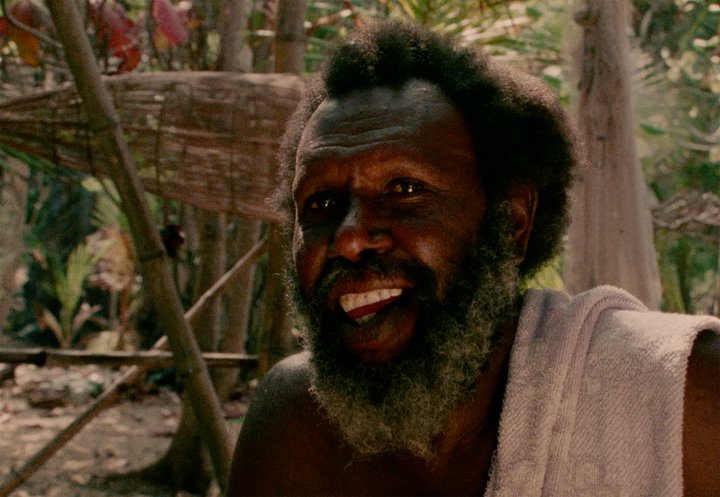

and powerful Cavaradossi who reached those high notes with ease. Romaniw was empassioned and exquisite – even in a park and with an audience this big, you could have heard a pin drop during ‘Vissi d’arte‘. At the end, everyone was on their feet and clapping and cheering ( and booing Scarpia, who was an excellent Roland Wood ). Though there were also folk beginning to clear away their things – it was cold by this time. The group to the immediate right of us had brought duvets, they were snug. 1992 is an important year in Australian law and history because the High Court of Australia delivered a landmark ruling known as the ‘Mabo decision’. This overturned the legal concept of ‘terra nullius’ – land belonging to nobody – which was used to justify taking over the land, occupied for thousands of years by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, that subsequently became known as Australia. Eddie Koiki Mabo was a Torres Strait Islander, a Meriam man, who, along with other Islanders, filed a claim in the High Court for native title to portions of Mer Island. After ten years, on 3rd June 1992, the High Court found for Eddie, who had died of cancer five months earlier. 3rd June is celebrated as ‘Mabo Day’ in the Torres Strait Islands and there is an ongoing campaign to make it a national Australian holiday. This exhibition looks at artworks inspired by the relationship between land and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people, sometimes created in response to land disputes and colonialism.

1992 is an important year in Australian law and history because the High Court of Australia delivered a landmark ruling known as the ‘Mabo decision’. This overturned the legal concept of ‘terra nullius’ – land belonging to nobody – which was used to justify taking over the land, occupied for thousands of years by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, that subsequently became known as Australia. Eddie Koiki Mabo was a Torres Strait Islander, a Meriam man, who, along with other Islanders, filed a claim in the High Court for native title to portions of Mer Island. After ten years, on 3rd June 1992, the High Court found for Eddie, who had died of cancer five months earlier. 3rd June is celebrated as ‘Mabo Day’ in the Torres Strait Islands and there is an ongoing campaign to make it a national Australian holiday. This exhibition looks at artworks inspired by the relationship between land and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people, sometimes created in response to land disputes and colonialism. one sees at the very start of the exhibition on the Aitsis Map. I had understood a little about the connection between the Aboriginal people and the land, a reciprocal and custodial relationship. They do not ‘own’ it in the European sense of dividing and apportioning pieces of land, but have an ongoing cultural connection with it, which underpins their history, spiritual beliefs, language, lore, family and identity. This is inherent in the art of contemporary artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Dale Harding and John Mawurndjul ( I loved his woven female ancestor ).

one sees at the very start of the exhibition on the Aitsis Map. I had understood a little about the connection between the Aboriginal people and the land, a reciprocal and custodial relationship. They do not ‘own’ it in the European sense of dividing and apportioning pieces of land, but have an ongoing cultural connection with it, which underpins their history, spiritual beliefs, language, lore, family and identity. This is inherent in the art of contemporary artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Dale Harding and John Mawurndjul ( I loved his woven female ancestor ).

Given the antiquity of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and the cultural influence it has had over the millennia it’s not surprising that large numbers of visual artists have been inspired by it. Followers of my twitter feed will know I have been collecting and sharing images of Delphi, the Temple of Apollo and the various historical or mythical beings who came there, drawn or painted by famous artists. So, we’ve had Gustave Dore’s Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes or Furies (left), Edward Lear’s water colour of the Phaedriades, the massive cliffs which loom over the Temple site and William Blake’s illustration for ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ showing ‘The Overthrow of Apollo and the Pagan Gods’.

Given the antiquity of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and the cultural influence it has had over the millennia it’s not surprising that large numbers of visual artists have been inspired by it. Followers of my twitter feed will know I have been collecting and sharing images of Delphi, the Temple of Apollo and the various historical or mythical beings who came there, drawn or painted by famous artists. So, we’ve had Gustave Dore’s Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes or Furies (left), Edward Lear’s water colour of the Phaedriades, the massive cliffs which loom over the Temple site and William Blake’s illustration for ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ showing ‘The Overthrow of Apollo and the Pagan Gods’. events or characters from Greek drama set at Delphi. On Greek redware (right) for example, showing the sleeping Erinyes being roused from their Apollo-induced slumber by the vengeful spirit of Clytemnestra, urging them to hunt down her son, and murderer, Orestes ( from Eumenides by Aeschylus ). Later paintings include Orestes being pursued by the same furies by, among others, John Singer Sergeant, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, John Flaxman and Franz Stuck, until we’re up to date with John Wilson (after Bouguereau).

events or characters from Greek drama set at Delphi. On Greek redware (right) for example, showing the sleeping Erinyes being roused from their Apollo-induced slumber by the vengeful spirit of Clytemnestra, urging them to hunt down her son, and murderer, Orestes ( from Eumenides by Aeschylus ). Later paintings include Orestes being pursued by the same furies by, among others, John Singer Sergeant, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, John Flaxman and Franz Stuck, until we’re up to date with John Wilson (after Bouguereau). own versions, like that in Puck magazine (1877) or in Punch (left). In this instance it is the Rt. Hon. John Bright MP who is in the Orestes role, being pursued by the vested interests which he opposed through the Anti-Corn Law League. It was Bright, famous for his oratorical skills among other things, who coined the phrase ‘Mother of Parliaments’. He is also credited with first using the phrase ‘flogging a dead horse’ to illustrate the pointlessness of certain activities (in Bright’s case this meant getting the House of Commons to consider Parliamentary reform – ’twas ever thus).

own versions, like that in Puck magazine (1877) or in Punch (left). In this instance it is the Rt. Hon. John Bright MP who is in the Orestes role, being pursued by the vested interests which he opposed through the Anti-Corn Law League. It was Bright, famous for his oratorical skills among other things, who coined the phrase ‘Mother of Parliaments’. He is also credited with first using the phrase ‘flogging a dead horse’ to illustrate the pointlessness of certain activities (in Bright’s case this meant getting the House of Commons to consider Parliamentary reform – ’twas ever thus). Wenceslas Holler etched them in the seventeenth century (right) and they have re-emerged in modern day gaming ( though with a rather different, sexy, look which speaks to who it is who plays those games rather than any mythological authenticity ). Naked the furies may have, traditionally, been, but not looking like a set of pouting, come-hither dominatrices.

Wenceslas Holler etched them in the seventeenth century (right) and they have re-emerged in modern day gaming ( though with a rather different, sexy, look which speaks to who it is who plays those games rather than any mythological authenticity ). Naked the furies may have, traditionally, been, but not looking like a set of pouting, come-hither dominatrices. The Pythia, or priestess of Apollo who spoke, as the Oracle, with Apollo’s voice is also a favourite subject in paint and in sculpture. Eugene Delacroix showed Lycurgus consulting her, John Collier made her a hooded, pre-raphaelite religious perched high on her tripod or three-legged stool (left). Note the gases swirling upwards from the crack in the floor of her underground room, the inhalation of which led to her madness and prophecies. No such crevice has been found at the Temple site, but, as a character explains in the book “geologists have found that two geological fault lines cross beneath Delphi, with fissures under the Temple itself which allow small amounts of naturally occurring gas to rise to the surface. Rock testing showed ethane, methane and ethylene − formerly used as an anaesthetic − to be present. These would create a calm, trancelike state and, if a lot was consumed, a form of wild mania.”

The Pythia, or priestess of Apollo who spoke, as the Oracle, with Apollo’s voice is also a favourite subject in paint and in sculpture. Eugene Delacroix showed Lycurgus consulting her, John Collier made her a hooded, pre-raphaelite religious perched high on her tripod or three-legged stool (left). Note the gases swirling upwards from the crack in the floor of her underground room, the inhalation of which led to her madness and prophecies. No such crevice has been found at the Temple site, but, as a character explains in the book “geologists have found that two geological fault lines cross beneath Delphi, with fissures under the Temple itself which allow small amounts of naturally occurring gas to rise to the surface. Rock testing showed ethane, methane and ethylene − formerly used as an anaesthetic − to be present. These would create a calm, trancelike state and, if a lot was consumed, a form of wild mania.” …and things are more familiar. The activity which accompanies publishing a crime fiction book was new to me with Plague, but this time, with Oracle, it’s less so. There are fewer decisions than last time because much has already been determined, Oracle will be consistent with Plague, in size, in print, in design. It even has approximately the same number of pages.

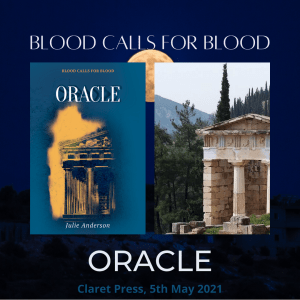

…and things are more familiar. The activity which accompanies publishing a crime fiction book was new to me with Plague, but this time, with Oracle, it’s less so. There are fewer decisions than last time because much has already been determined, Oracle will be consistent with Plague, in size, in print, in design. It even has approximately the same number of pages. these days such images come in various forms – Facebook banners, Instagram posts and Twitter headers – and some come with animation. The one on the right is an Instagram post, which uses a photograph of the Treasury of the Athenians at the Temple of Apollo, Delphi, as well as a copy of the cover and its tagline – ‘Blood calls for blood’ on a background of a full moon rising above a hillside. There is an animated version of this too.

these days such images come in various forms – Facebook banners, Instagram posts and Twitter headers – and some come with animation. The one on the right is an Instagram post, which uses a photograph of the Treasury of the Athenians at the Temple of Apollo, Delphi, as well as a copy of the cover and its tagline – ‘Blood calls for blood’ on a background of a full moon rising above a hillside. There is an animated version of this too. dramatic. I think it’s eye-catching. I just hope that the book isn’t mIstaken for a vampire novel (because of that tag-line). A number of early readers of Plague thought, from the blurb, that it was about a pandemic. No fear of misunderstanding the title this time, the blurb makes reference to the ancient oracle, but who knows what else people with think of.

dramatic. I think it’s eye-catching. I just hope that the book isn’t mIstaken for a vampire novel (because of that tag-line). A number of early readers of Plague thought, from the blurb, that it was about a pandemic. No fear of misunderstanding the title this time, the blurb makes reference to the ancient oracle, but who knows what else people with think of. There are some differences too, in part because I’ve learned from experience. So, for example, there’s an Oracle postcard to send out with review copies (last time I exhausted my personal stock of notelets). Claret is having the ARCs printed at the moment and I’ll be looking to take receipt of boxes of books in the next week or so. The other, more exciting thing is that readers are telling me that they’re waiting for the book to come out ( the virtue of having a series ). Also, it seems, there are a lot more media events – interviews, talks, blogs, podcasts – than last time. In part, I suspect because I have more media contacts now (and I’m good value i.e. or the most part, free), but also because I’m no longer an unknown. That Oracle is ‘the further adventures of…’ helps.

There are some differences too, in part because I’ve learned from experience. So, for example, there’s an Oracle postcard to send out with review copies (last time I exhausted my personal stock of notelets). Claret is having the ARCs printed at the moment and I’ll be looking to take receipt of boxes of books in the next week or so. The other, more exciting thing is that readers are telling me that they’re waiting for the book to come out ( the virtue of having a series ). Also, it seems, there are a lot more media events – interviews, talks, blogs, podcasts – than last time. In part, I suspect because I have more media contacts now (and I’m good value i.e. or the most part, free), but also because I’m no longer an unknown. That Oracle is ‘the further adventures of…’ helps. My new crime thriller Oracle is set in Delphi, Greece, close to the ancient Temple of Apollo half way up Mount Parnassus. The crimes happen during an international conference taking place at the European Cultural Centre which lies just outside the town of Delphi. The ECCD is a real place, which I visited at the end of last century when I attended a conference there.

My new crime thriller Oracle is set in Delphi, Greece, close to the ancient Temple of Apollo half way up Mount Parnassus. The crimes happen during an international conference taking place at the European Cultural Centre which lies just outside the town of Delphi. The ECCD is a real place, which I visited at the end of last century when I attended a conference there.

Aside from the view and the nearby ancient Temple, I remember its fine, confident modern architecture, using local stone as well as concrete and lots of glass – making the most of those spectacular views. My heroine, Cassandra, occupies one of the rooms in the Guesthouse (left) above the restaurant on the ground floor.

Aside from the view and the nearby ancient Temple, I remember its fine, confident modern architecture, using local stone as well as concrete and lots of glass – making the most of those spectacular views. My heroine, Cassandra, occupies one of the rooms in the Guesthouse (left) above the restaurant on the ground floor. raining, but the mountain peaks were snow covered. As I sat in that same restaurant with a storm raging outside and the lights flickering, briefly, a fellow conference goer suggested that it would be a tremendous place for a murder mystery. Over twenty years later, when Claret Press suggested that I write one, the ECCD and the beautiful ancient temple nearby immediately sprang to mind.

raining, but the mountain peaks were snow covered. As I sat in that same restaurant with a storm raging outside and the lights flickering, briefly, a fellow conference goer suggested that it would be a tremendous place for a murder mystery. Over twenty years later, when Claret Press suggested that I write one, the ECCD and the beautiful ancient temple nearby immediately sprang to mind. So it was Delphi, not London, which was the setting which I thought of first, but it soon became apparent to me that my first book, introducing the recurring character of my detective and her associates, should be set where most of the books would be taking place and that was London. From there on it had to be Westminster and Thorney Island, places which I knew very well, having trodden the streets there for years. Thus was Plague born. At the end of Oracle it is where Cassie returns to for the third book in the series, Opera, although I confess that I do have a yen to take her off to Rome at some point in the future, another city which I know very well.

So it was Delphi, not London, which was the setting which I thought of first, but it soon became apparent to me that my first book, introducing the recurring character of my detective and her associates, should be set where most of the books would be taking place and that was London. From there on it had to be Westminster and Thorney Island, places which I knew very well, having trodden the streets there for years. Thus was Plague born. At the end of Oracle it is where Cassie returns to for the third book in the series, Opera, although I confess that I do have a yen to take her off to Rome at some point in the future, another city which I know very well. Maybe it’s because I’m preparing a talk on Politics and Prose for the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea and Westminster Libraries ( it’s free and happening on 25th January if anyone is interested, see Eventbrite

Maybe it’s because I’m preparing a talk on Politics and Prose for the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea and Westminster Libraries ( it’s free and happening on 25th January if anyone is interested, see Eventbrite  others. The crude and barbaric terror of the Stalinist period is shown, full throttle, where the answer to any problem was murder and truth was what the most powerful said it was. It’s a mesmerising and very funny film, in an absurdist way, but it’s also not comfortable watching. If you haven’t seen it, I can definitely recommend it.

others. The crude and barbaric terror of the Stalinist period is shown, full throttle, where the answer to any problem was murder and truth was what the most powerful said it was. It’s a mesmerising and very funny film, in an absurdist way, but it’s also not comfortable watching. If you haven’t seen it, I can definitely recommend it. the tight-knit nature of U.S. politics – the intern is the daughter of the Committee member, the rival campaign managers are well-known to each other (each trying to exploit the other’s known foibles ). It’s a quieter film which depicts an inhuman and corrupt world – hardly news – but does so through the prism of one man’s ambition and where it leads. Again, recommended.

the tight-knit nature of U.S. politics – the intern is the daughter of the Committee member, the rival campaign managers are well-known to each other (each trying to exploit the other’s known foibles ). It’s a quieter film which depicts an inhuman and corrupt world – hardly news – but does so through the prism of one man’s ambition and where it leads. Again, recommended. Anyone who remembers the wit of The West Wing won’t be surprised by that on show here, it made this viewer laugh out loud a few times, though with a bitter twist. This truly was a ‘political trial’. It’s also a clever depiction of a moment in time rather in the way that the TV series Mrs America captured the spirit of the 1970s political backlash to the 60s. I strongly recommend you watch this film.

Anyone who remembers the wit of The West Wing won’t be surprised by that on show here, it made this viewer laugh out loud a few times, though with a bitter twist. This truly was a ‘political trial’. It’s also a clever depiction of a moment in time rather in the way that the TV series Mrs America captured the spirit of the 1970s political backlash to the 60s. I strongly recommend you watch this film. I’ll be exploring how politics is depicted in stories, as well as discussing what a ‘political novel’ is in my talk on 25th January.

I’ll be exploring how politics is depicted in stories, as well as discussing what a ‘political novel’ is in my talk on 25th January. imagined as well as the archaeological city. I spent several happy hours in it yesterday (and will be returning next week).

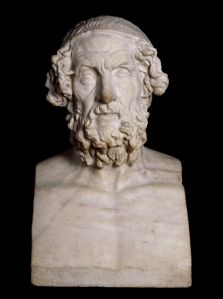

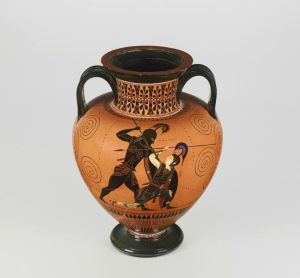

imagined as well as the archaeological city. I spent several happy hours in it yesterday (and will be returning next week). from the coloured figures, like those on the large two handled pot depicting Achilles killing Amazon Queen Penthisiliea (right) or the Judgement of Paris on a wine krater, to the delicate line drawings showing Briseis being led away from Achilles’ tent. I will also remember the stone bas relief showing this scene, with Achilles looking away in anger, but Patroclus placing a consolatory hand on Briseis’ shoulder as she is collected by Agamemnon’s soldier. A tender gesture.

from the coloured figures, like those on the large two handled pot depicting Achilles killing Amazon Queen Penthisiliea (right) or the Judgement of Paris on a wine krater, to the delicate line drawings showing Briseis being led away from Achilles’ tent. I will also remember the stone bas relief showing this scene, with Achilles looking away in anger, but Patroclus placing a consolatory hand on Briseis’ shoulder as she is collected by Agamemnon’s soldier. A tender gesture. It is testament to the power of the ancient story that the characters live so vividly again. But then, the story has been told and retold, as evidenced by the lines from the epics scribbled by ancient Roman children on the papyri copy books displayed. Its retelling is brought bang up to date with the poster from the, much derided, 21st century Hollywood film Troy and modern versions of The Judgement of Paris – photographic – and The Siren’s Song ( see left for the ancient depiction, below for the modern collage by Romare Bearden ). Aficionados of the male body please note, Brad Pitt has quite a lot of competition in the buffed masculinity stakes, though it’s interesting that, even where a ‘hero’ such as Odysseus is obviously beyond youth and is depicted on artefacts with an older face, his body is still drawn as youthfully ideal. Hollywood’s fixation with perfect bodies is nothing new.

It is testament to the power of the ancient story that the characters live so vividly again. But then, the story has been told and retold, as evidenced by the lines from the epics scribbled by ancient Roman children on the papyri copy books displayed. Its retelling is brought bang up to date with the poster from the, much derided, 21st century Hollywood film Troy and modern versions of The Judgement of Paris – photographic – and The Siren’s Song ( see left for the ancient depiction, below for the modern collage by Romare Bearden ). Aficionados of the male body please note, Brad Pitt has quite a lot of competition in the buffed masculinity stakes, though it’s interesting that, even where a ‘hero’ such as Odysseus is obviously beyond youth and is depicted on artefacts with an older face, his body is still drawn as youthfully ideal. Hollywood’s fixation with perfect bodies is nothing new. There is a very interesting section on the real city of Troy, or what we now believe is the real city. Not Schliemann’s much too early, if appropriately burnt, discovery but a later version. I didn’t realise just how many Troys there were, built on top of one another, but there are informative graphics showing just how these cities developed and when. Indeed the whole exhibition is well organised, with clearly written and illuminating captions. Technology, from the annotated drawings in light of

There is a very interesting section on the real city of Troy, or what we now believe is the real city. Not Schliemann’s much too early, if appropriately burnt, discovery but a later version. I didn’t realise just how many Troys there were, built on top of one another, but there are informative graphics showing just how these cities developed and when. Indeed the whole exhibition is well organised, with clearly written and illuminating captions. Technology, from the annotated drawings in light of  various pieces of complex decoration to help the viewer unscramble some of the detail, to the videos showing the massing levels of the different Troys is used cleverly and well.

various pieces of complex decoration to help the viewer unscramble some of the detail, to the videos showing the massing levels of the different Troys is used cleverly and well.