I’ve recently been out and about looking at the places in London where the third book in the Cassandra Fortune series, entitled ‘Opera‘, is set. The obvious one, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, is not yet open to anyone but ticket holders to socially distanced performances ( though I have a contact there for when it opens more widely ), but there are others, less obvious and, to non-Londoners, perhaps something of a revelation. If ‘Plague‘ was set in places that we all know, even if it took you to parts of those places which are usually closed to view, or hidden, ‘Opera’ will introduce some settings which are less well-known, but, I hope, people may then visit.

I’ve recently been out and about looking at the places in London where the third book in the Cassandra Fortune series, entitled ‘Opera‘, is set. The obvious one, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, is not yet open to anyone but ticket holders to socially distanced performances ( though I have a contact there for when it opens more widely ), but there are others, less obvious and, to non-Londoners, perhaps something of a revelation. If ‘Plague‘ was set in places that we all know, even if it took you to parts of those places which are usually closed to view, or hidden, ‘Opera’ will introduce some settings which are less well-known, but, I hope, people may then visit.

I visited one of these last week, just before the heatwave hit. Cloudy weather notwithstanding, Brompton Cemetery was still a delight to visit. Designed as a ‘Garden Cemetery’ and meant, from its inception, to be a public space as well as a last resting place, the cemetery stretches over a long, rectangular-shaped forty acres on the Fulham Chelsea borders. It has a grand entrance lodge gate at its northern extremity which houses a café, an information centre and exhibition space ( and which will feature in the book ) and which looks down a grand main avenue towards the chapel and colonnade at the far end.

The main avenue is flanked by the grander grave markers and mausolea, this was the most public and therefore the most expensive part of the cemetery to bury your loved ones. The side avenues and circles have their fair share of statuary and raised tombs too, though the still working part of the cemetery to the west is in a lower key. On Wednesday, when I visited, the cow parsley was rampant and allowed to be so, only the edges of the lawns next to the avenues were mown ( except for the railed section of the cemetery which belongs to the Brigade of Guards and which was fully mown with military precision ). Butterflies and bees were plentiful, the latter possibly living in the cemetery bee hives still kept on the west side of the cemetery.

Brompton is one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ Victorian cemeteries, which includes Highgate, with its graves of Karl Marx, George Eliot and other very famous people and Kelsall Green with its oft-filmed catacombs. While well known to locals – and a godsend during lockdowns – it is less widely known than these others. Both Kelsall Green and Tower Hamlets ( another Magnificent Seven cemetery ) featured in ‘Plague’. Brompton is owned by the Crown and run by The Royal Parks and includes many military graves, including of Commonwealth service personnel maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and many Czechoslovak, Polish and Russian military burials. It is also evidence of the diversity of Victorian London, housing as it did and does, the remains of individuals ranging from Chief Long Wolf of the Ogulala Sioux nation to Johannes Zukertorte, Jewish-Polish chess grandmaster and the Keeley and Vokes families, music hall artistes and actors. Other individuals buried here include a Mr Nutkin, Mr Brock, Mr Tod, Jeremiah Fisher and Peter Rabbett – Beatrix Potter lived nearby and was known to walk in the cemetery often, did these names inspire her?

Brompton is one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ Victorian cemeteries, which includes Highgate, with its graves of Karl Marx, George Eliot and other very famous people and Kelsall Green with its oft-filmed catacombs. While well known to locals – and a godsend during lockdowns – it is less widely known than these others. Both Kelsall Green and Tower Hamlets ( another Magnificent Seven cemetery ) featured in ‘Plague’. Brompton is owned by the Crown and run by The Royal Parks and includes many military graves, including of Commonwealth service personnel maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and many Czechoslovak, Polish and Russian military burials. It is also evidence of the diversity of Victorian London, housing as it did and does, the remains of individuals ranging from Chief Long Wolf of the Ogulala Sioux nation to Johannes Zukertorte, Jewish-Polish chess grandmaster and the Keeley and Vokes families, music hall artistes and actors. Other individuals buried here include a Mr Nutkin, Mr Brock, Mr Tod, Jeremiah Fisher and Peter Rabbett – Beatrix Potter lived nearby and was known to walk in the cemetery often, did these names inspire her?

The Chapel at the cemetery’s southern end wasn’t open last week, but the grand colonnade is open all year round. Built in a style aping that of St Peter’s Square in Rome, the Colonnade runs above catacombs, which were fashionable for a brief time in Victorian London ( all too brief, additional catacombs built along the west side of the cemetery were never fully occupied ). The steps down to them are very wide and shallow, mainly because the lead-lined coffins deemed necessary for catacomb interment were extremely heavy and therefore difficult for pallbearers to carry and manoeuvre. The catacombs themselves are not open to the public except on special tours and open days and the locked metal doors, with their sculpted serpentine bas reliefs offer tantalising glimpses within.

The Chapel at the cemetery’s southern end wasn’t open last week, but the grand colonnade is open all year round. Built in a style aping that of St Peter’s Square in Rome, the Colonnade runs above catacombs, which were fashionable for a brief time in Victorian London ( all too brief, additional catacombs built along the west side of the cemetery were never fully occupied ). The steps down to them are very wide and shallow, mainly because the lead-lined coffins deemed necessary for catacomb interment were extremely heavy and therefore difficult for pallbearers to carry and manoeuvre. The catacombs themselves are not open to the public except on special tours and open days and the locked metal doors, with their sculpted serpentine bas reliefs offer tantalising glimpses within.

If you happen to be in West London and have an hour or so to spare, you could do worse than spend it in this tranquil and interesting haven from the city which surrounds it. I will, most certainly, be back.

At Delphi it was the Pythia who spoke for the god Apollo – ‘prophet’ or prophetess’ originally meaning ‘spokesperson’. At Cumae it was the similarly Apollonian Sibyl and at Siwah in Egypt another sibyl, supposedly of the line of Poseidon and related to Nile, spoke for Zeus-Ammon. The first two were real women and, unusually for much of the ancient world, women who had power. They were actually a succession of women who filled the ‘office’ of Pythia or Sibyl ( although it is said that the most famous of the latter was granted extra long life and lived until very old, shrunken and wizened ). They certainly helped determine policy. As Cicero says of the Delphic Pythia, there wasn’t a important decision taken in the ancient Greek world without consulting her.

At Delphi it was the Pythia who spoke for the god Apollo – ‘prophet’ or prophetess’ originally meaning ‘spokesperson’. At Cumae it was the similarly Apollonian Sibyl and at Siwah in Egypt another sibyl, supposedly of the line of Poseidon and related to Nile, spoke for Zeus-Ammon. The first two were real women and, unusually for much of the ancient world, women who had power. They were actually a succession of women who filled the ‘office’ of Pythia or Sibyl ( although it is said that the most famous of the latter was granted extra long life and lived until very old, shrunken and wizened ). They certainly helped determine policy. As Cicero says of the Delphic Pythia, there wasn’t a important decision taken in the ancient Greek world without consulting her. most famous prediction was probably that given to King Croesus of Lydia ( the Croesus who was so rich that his name became a byword for wealth – ‘as rich as Croesus’ ). Croesus, who had clearly hoped to find favour with the Pythia by sending her vast quantities of gold, was pondering whether or not to invade the neighbouring kingdom of Persia, then ruled by Cyrus. She advised him that, should he do so, he would destroy a great empire. Croesus duly launched his campaign in 547 BCE. After some inconclusive fighting, Cyrus defeated Croesus at Thymbria in 546 and Croesus took refuge in his capital of Sardis. The Siege of Sardis resulted in his capture and the Persians went on to annex Lydia. It was then clear that the empire which the Pythia foresaw Croesus destroying was his own.

most famous prediction was probably that given to King Croesus of Lydia ( the Croesus who was so rich that his name became a byword for wealth – ‘as rich as Croesus’ ). Croesus, who had clearly hoped to find favour with the Pythia by sending her vast quantities of gold, was pondering whether or not to invade the neighbouring kingdom of Persia, then ruled by Cyrus. She advised him that, should he do so, he would destroy a great empire. Croesus duly launched his campaign in 547 BCE. After some inconclusive fighting, Cyrus defeated Croesus at Thymbria in 546 and Croesus took refuge in his capital of Sardis. The Siege of Sardis resulted in his capture and the Persians went on to annex Lydia. It was then clear that the empire which the Pythia foresaw Croesus destroying was his own. The Pythia’s fame was assured and she features in drama, poetry, histories and other writings from about the sixth century BCE onwards ( although there was a priestess of legend supposedly at Delphi before then ). The Sibyl of Cumae may not have been quite as well known, but she had her adherents too, especially in the Roman period, and legendary stories grew up around her. The most famous was probably that involving Tarquin, the supposed last king of Rome, and the Sybilline books. An unknown woman arrived in Rome and offered to sell the king nine books of prophesies. Given the enormous sum she asked for them Tarquin refused to buy. She burnt three of them and asked the same price for the remaining six. Again Tarquin refused and she burned another three. Only three books remained, but Tarquin relented and bought them, for the original asking price for the nine. At which point the woman disappeared and the books were stored in the temple of Capitoline Jove on the Capitol. They were burned in a subsequent fire.

The Pythia’s fame was assured and she features in drama, poetry, histories and other writings from about the sixth century BCE onwards ( although there was a priestess of legend supposedly at Delphi before then ). The Sibyl of Cumae may not have been quite as well known, but she had her adherents too, especially in the Roman period, and legendary stories grew up around her. The most famous was probably that involving Tarquin, the supposed last king of Rome, and the Sybilline books. An unknown woman arrived in Rome and offered to sell the king nine books of prophesies. Given the enormous sum she asked for them Tarquin refused to buy. She burnt three of them and asked the same price for the remaining six. Again Tarquin refused and she burned another three. Only three books remained, but Tarquin relented and bought them, for the original asking price for the nine. At which point the woman disappeared and the books were stored in the temple of Capitoline Jove on the Capitol. They were burned in a subsequent fire. too was visited by Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt and though history doesn’t record how he treated the people there, it does say he went away content. The Siwah Oracle, wisely, forbade its supplicants from discussing what the Oracle had said, which pre-empted the examination of its prophesies which other prophetic Oracles were subject to. Unfortunately this also means we don’t have the wonderful stories about this oracle that we have about the other two. The legendary Sybil at Siwah was supposedly the daughter of Lamia, herself the daughter of Poseidon, God of the sea ( and she appears in Euripides play, Lamia ).

too was visited by Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt and though history doesn’t record how he treated the people there, it does say he went away content. The Siwah Oracle, wisely, forbade its supplicants from discussing what the Oracle had said, which pre-empted the examination of its prophesies which other prophetic Oracles were subject to. Unfortunately this also means we don’t have the wonderful stories about this oracle that we have about the other two. The legendary Sybil at Siwah was supposedly the daughter of Lamia, herself the daughter of Poseidon, God of the sea ( and she appears in Euripides play, Lamia ). Given the antiquity of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and the cultural influence it has had over the millennia it’s not surprising that large numbers of visual artists have been inspired by it. Followers of my twitter feed will know I have been collecting and sharing images of Delphi, the Temple of Apollo and the various historical or mythical beings who came there, drawn or painted by famous artists. So, we’ve had Gustave Dore’s Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes or Furies (left), Edward Lear’s water colour of the Phaedriades, the massive cliffs which loom over the Temple site and William Blake’s illustration for ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ showing ‘The Overthrow of Apollo and the Pagan Gods’.

Given the antiquity of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and the cultural influence it has had over the millennia it’s not surprising that large numbers of visual artists have been inspired by it. Followers of my twitter feed will know I have been collecting and sharing images of Delphi, the Temple of Apollo and the various historical or mythical beings who came there, drawn or painted by famous artists. So, we’ve had Gustave Dore’s Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes or Furies (left), Edward Lear’s water colour of the Phaedriades, the massive cliffs which loom over the Temple site and William Blake’s illustration for ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ showing ‘The Overthrow of Apollo and the Pagan Gods’. events or characters from Greek drama set at Delphi. On Greek redware (right) for example, showing the sleeping Erinyes being roused from their Apollo-induced slumber by the vengeful spirit of Clytemnestra, urging them to hunt down her son, and murderer, Orestes ( from Eumenides by Aeschylus ). Later paintings include Orestes being pursued by the same furies by, among others, John Singer Sergeant, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, John Flaxman and Franz Stuck, until we’re up to date with John Wilson (after Bouguereau).

events or characters from Greek drama set at Delphi. On Greek redware (right) for example, showing the sleeping Erinyes being roused from their Apollo-induced slumber by the vengeful spirit of Clytemnestra, urging them to hunt down her son, and murderer, Orestes ( from Eumenides by Aeschylus ). Later paintings include Orestes being pursued by the same furies by, among others, John Singer Sergeant, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, John Flaxman and Franz Stuck, until we’re up to date with John Wilson (after Bouguereau). own versions, like that in Puck magazine (1877) or in Punch (left). In this instance it is the Rt. Hon. John Bright MP who is in the Orestes role, being pursued by the vested interests which he opposed through the Anti-Corn Law League. It was Bright, famous for his oratorical skills among other things, who coined the phrase ‘Mother of Parliaments’. He is also credited with first using the phrase ‘flogging a dead horse’ to illustrate the pointlessness of certain activities (in Bright’s case this meant getting the House of Commons to consider Parliamentary reform – ’twas ever thus).

own versions, like that in Puck magazine (1877) or in Punch (left). In this instance it is the Rt. Hon. John Bright MP who is in the Orestes role, being pursued by the vested interests which he opposed through the Anti-Corn Law League. It was Bright, famous for his oratorical skills among other things, who coined the phrase ‘Mother of Parliaments’. He is also credited with first using the phrase ‘flogging a dead horse’ to illustrate the pointlessness of certain activities (in Bright’s case this meant getting the House of Commons to consider Parliamentary reform – ’twas ever thus). Wenceslas Holler etched them in the seventeenth century (right) and they have re-emerged in modern day gaming ( though with a rather different, sexy, look which speaks to who it is who plays those games rather than any mythological authenticity ). Naked the furies may have, traditionally, been, but not looking like a set of pouting, come-hither dominatrices.

Wenceslas Holler etched them in the seventeenth century (right) and they have re-emerged in modern day gaming ( though with a rather different, sexy, look which speaks to who it is who plays those games rather than any mythological authenticity ). Naked the furies may have, traditionally, been, but not looking like a set of pouting, come-hither dominatrices. The Pythia, or priestess of Apollo who spoke, as the Oracle, with Apollo’s voice is also a favourite subject in paint and in sculpture. Eugene Delacroix showed Lycurgus consulting her, John Collier made her a hooded, pre-raphaelite religious perched high on her tripod or three-legged stool (left). Note the gases swirling upwards from the crack in the floor of her underground room, the inhalation of which led to her madness and prophecies. No such crevice has been found at the Temple site, but, as a character explains in the book “geologists have found that two geological fault lines cross beneath Delphi, with fissures under the Temple itself which allow small amounts of naturally occurring gas to rise to the surface. Rock testing showed ethane, methane and ethylene − formerly used as an anaesthetic − to be present. These would create a calm, trancelike state and, if a lot was consumed, a form of wild mania.”

The Pythia, or priestess of Apollo who spoke, as the Oracle, with Apollo’s voice is also a favourite subject in paint and in sculpture. Eugene Delacroix showed Lycurgus consulting her, John Collier made her a hooded, pre-raphaelite religious perched high on her tripod or three-legged stool (left). Note the gases swirling upwards from the crack in the floor of her underground room, the inhalation of which led to her madness and prophecies. No such crevice has been found at the Temple site, but, as a character explains in the book “geologists have found that two geological fault lines cross beneath Delphi, with fissures under the Temple itself which allow small amounts of naturally occurring gas to rise to the surface. Rock testing showed ethane, methane and ethylene − formerly used as an anaesthetic − to be present. These would create a calm, trancelike state and, if a lot was consumed, a form of wild mania.” …and things are more familiar. The activity which accompanies publishing a crime fiction book was new to me with Plague, but this time, with Oracle, it’s less so. There are fewer decisions than last time because much has already been determined, Oracle will be consistent with Plague, in size, in print, in design. It even has approximately the same number of pages.

…and things are more familiar. The activity which accompanies publishing a crime fiction book was new to me with Plague, but this time, with Oracle, it’s less so. There are fewer decisions than last time because much has already been determined, Oracle will be consistent with Plague, in size, in print, in design. It even has approximately the same number of pages. these days such images come in various forms – Facebook banners, Instagram posts and Twitter headers – and some come with animation. The one on the right is an Instagram post, which uses a photograph of the Treasury of the Athenians at the Temple of Apollo, Delphi, as well as a copy of the cover and its tagline – ‘Blood calls for blood’ on a background of a full moon rising above a hillside. There is an animated version of this too.

these days such images come in various forms – Facebook banners, Instagram posts and Twitter headers – and some come with animation. The one on the right is an Instagram post, which uses a photograph of the Treasury of the Athenians at the Temple of Apollo, Delphi, as well as a copy of the cover and its tagline – ‘Blood calls for blood’ on a background of a full moon rising above a hillside. There is an animated version of this too. As I did for the launch of Plague, I’ve uploaded a new Facebook and a new Twitter Header, using the new banner shown below, which also now lies beneath my email signature. This includes the same images as the Instagram post, with the addition of a rather wonderful artwork by Gustave Dore. The engraving is one of the French master illustrator’s pieces for The Divine Comedy, Canto IX ( 1867) and it shows Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes, or Furies. It is entitled ‘Megaera, Tisipone and Alecto’, so I would imagine this might get used quite a lot ( it’s also out of copyright ). I’ve always been a Dore admirer and I’m not alone. As the Tate’s exhibition on Van Gogh showed, the Dutch painter loved Dore’s work and collected it, basing some of his own compositions on Dore engravings. This image appears in the banner, with the others, set against a background of black, with a wisp of blue/grey smoke curling across it and the tagline, which is in red this time. Very

As I did for the launch of Plague, I’ve uploaded a new Facebook and a new Twitter Header, using the new banner shown below, which also now lies beneath my email signature. This includes the same images as the Instagram post, with the addition of a rather wonderful artwork by Gustave Dore. The engraving is one of the French master illustrator’s pieces for The Divine Comedy, Canto IX ( 1867) and it shows Dante and Virgil encountering the Erinyes, or Furies. It is entitled ‘Megaera, Tisipone and Alecto’, so I would imagine this might get used quite a lot ( it’s also out of copyright ). I’ve always been a Dore admirer and I’m not alone. As the Tate’s exhibition on Van Gogh showed, the Dutch painter loved Dore’s work and collected it, basing some of his own compositions on Dore engravings. This image appears in the banner, with the others, set against a background of black, with a wisp of blue/grey smoke curling across it and the tagline, which is in red this time. Very dramatic. I think it’s eye-catching. I just hope that the book isn’t mIstaken for a vampire novel (because of that tag-line). A number of early readers of Plague thought, from the blurb, that it was about a pandemic. No fear of misunderstanding the title this time, the blurb makes reference to the ancient oracle, but who knows what else people with think of.

dramatic. I think it’s eye-catching. I just hope that the book isn’t mIstaken for a vampire novel (because of that tag-line). A number of early readers of Plague thought, from the blurb, that it was about a pandemic. No fear of misunderstanding the title this time, the blurb makes reference to the ancient oracle, but who knows what else people with think of. There are some differences too, in part because I’ve learned from experience. So, for example, there’s an Oracle postcard to send out with review copies (last time I exhausted my personal stock of notelets). Claret is having the ARCs printed at the moment and I’ll be looking to take receipt of boxes of books in the next week or so. The other, more exciting thing is that readers are telling me that they’re waiting for the book to come out ( the virtue of having a series ). Also, it seems, there are a lot more media events – interviews, talks, blogs, podcasts – than last time. In part, I suspect because I have more media contacts now (and I’m good value i.e. or the most part, free), but also because I’m no longer an unknown. That Oracle is ‘the further adventures of…’ helps.

There are some differences too, in part because I’ve learned from experience. So, for example, there’s an Oracle postcard to send out with review copies (last time I exhausted my personal stock of notelets). Claret is having the ARCs printed at the moment and I’ll be looking to take receipt of boxes of books in the next week or so. The other, more exciting thing is that readers are telling me that they’re waiting for the book to come out ( the virtue of having a series ). Also, it seems, there are a lot more media events – interviews, talks, blogs, podcasts – than last time. In part, I suspect because I have more media contacts now (and I’m good value i.e. or the most part, free), but also because I’m no longer an unknown. That Oracle is ‘the further adventures of…’ helps. My new crime thriller Oracle is set in Delphi, Greece, close to the ancient Temple of Apollo half way up Mount Parnassus. The crimes happen during an international conference taking place at the European Cultural Centre which lies just outside the town of Delphi. The ECCD is a real place, which I visited at the end of last century when I attended a conference there.

My new crime thriller Oracle is set in Delphi, Greece, close to the ancient Temple of Apollo half way up Mount Parnassus. The crimes happen during an international conference taking place at the European Cultural Centre which lies just outside the town of Delphi. The ECCD is a real place, which I visited at the end of last century when I attended a conference there.

Aside from the view and the nearby ancient Temple, I remember its fine, confident modern architecture, using local stone as well as concrete and lots of glass – making the most of those spectacular views. My heroine, Cassandra, occupies one of the rooms in the Guesthouse (left) above the restaurant on the ground floor.

Aside from the view and the nearby ancient Temple, I remember its fine, confident modern architecture, using local stone as well as concrete and lots of glass – making the most of those spectacular views. My heroine, Cassandra, occupies one of the rooms in the Guesthouse (left) above the restaurant on the ground floor. raining, but the mountain peaks were snow covered. As I sat in that same restaurant with a storm raging outside and the lights flickering, briefly, a fellow conference goer suggested that it would be a tremendous place for a murder mystery. Over twenty years later, when Claret Press suggested that I write one, the ECCD and the beautiful ancient temple nearby immediately sprang to mind.

raining, but the mountain peaks were snow covered. As I sat in that same restaurant with a storm raging outside and the lights flickering, briefly, a fellow conference goer suggested that it would be a tremendous place for a murder mystery. Over twenty years later, when Claret Press suggested that I write one, the ECCD and the beautiful ancient temple nearby immediately sprang to mind. So it was Delphi, not London, which was the setting which I thought of first, but it soon became apparent to me that my first book, introducing the recurring character of my detective and her associates, should be set where most of the books would be taking place and that was London. From there on it had to be Westminster and Thorney Island, places which I knew very well, having trodden the streets there for years. Thus was Plague born. At the end of Oracle it is where Cassie returns to for the third book in the series, Opera, although I confess that I do have a yen to take her off to Rome at some point in the future, another city which I know very well.

So it was Delphi, not London, which was the setting which I thought of first, but it soon became apparent to me that my first book, introducing the recurring character of my detective and her associates, should be set where most of the books would be taking place and that was London. From there on it had to be Westminster and Thorney Island, places which I knew very well, having trodden the streets there for years. Thus was Plague born. At the end of Oracle it is where Cassie returns to for the third book in the series, Opera, although I confess that I do have a yen to take her off to Rome at some point in the future, another city which I know very well. Back to Sunday, 21st January 1855 in a Trafalgar Square deep in snow, where about fifteen hundred people are gathering. They’re meeting to protest at the mismanagement and needless loss of life in the Crimean War, but can’t help larking about and they pelt passing traffic (and pedestrians) with snowballs. The police ask them to stop, but the protesters pelt the police too.

Back to Sunday, 21st January 1855 in a Trafalgar Square deep in snow, where about fifteen hundred people are gathering. They’re meeting to protest at the mismanagement and needless loss of life in the Crimean War, but can’t help larking about and they pelt passing traffic (and pedestrians) with snowballs. The police ask them to stop, but the protesters pelt the police too. but the failure to provide troops with the most basic necessities of life and the dreadful death rate resulting.

but the failure to provide troops with the most basic necessities of life and the dreadful death rate resulting. passed a vote demanding a full investigation. Lord Aberdeen, the Prime Minister, resigned on 30th January 1855.

passed a vote demanding a full investigation. Lord Aberdeen, the Prime Minister, resigned on 30th January 1855.  That’s what Britain still has. There are some service failures today – nothing is perfect – but these are often driven by politicians not civil servants, however much politicians seek to blame them (sometimes aided and abetted by the press). We touched on this in last night’s panel discussion on COVID, Corruption and Crony Capitalism, but we ran out of time before we could discuss why cronyism is so damaging to public service provision and so destructive of human lives. This article is by way of a reminder; January 1855 is where we were. Let’s not go back there.

That’s what Britain still has. There are some service failures today – nothing is perfect – but these are often driven by politicians not civil servants, however much politicians seek to blame them (sometimes aided and abetted by the press). We touched on this in last night’s panel discussion on COVID, Corruption and Crony Capitalism, but we ran out of time before we could discuss why cronyism is so damaging to public service provision and so destructive of human lives. This article is by way of a reminder; January 1855 is where we were. Let’s not go back there. Phew! I finally get to look forward to Christmas after the whirlwind of activity – talks, discussions, events, giveaways – which has accompanied the publication of my first crime thriller back in September. All something of an eye-opener to this writer, whose adventure books set in 13th century Spain never generated this much activity and interest. Even in a world reduced by COVID I’ve been very, very busy, almost always online. It’s been tremendous fun, by and large, and I’ve worked with and met some great people, online, on social media and, not least, the readers of my book.

Phew! I finally get to look forward to Christmas after the whirlwind of activity – talks, discussions, events, giveaways – which has accompanied the publication of my first crime thriller back in September. All something of an eye-opener to this writer, whose adventure books set in 13th century Spain never generated this much activity and interest. Even in a world reduced by COVID I’ve been very, very busy, almost always online. It’s been tremendous fun, by and large, and I’ve worked with and met some great people, online, on social media and, not least, the readers of my book. from a U3A crime fiction reading book group who have chosen Plague as their book for March and want me to do a talk for them, which I’m happy to do. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and Westminster people also seemed pleased, they have asked me to do another talk in January, this time about ‘Politics and Prose’ – political fiction in a time of increasing citizen journalism and social media commentary. That’s something I’ve blogged about in the past ( see

from a U3A crime fiction reading book group who have chosen Plague as their book for March and want me to do a talk for them, which I’m happy to do. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and Westminster people also seemed pleased, they have asked me to do another talk in January, this time about ‘Politics and Prose’ – political fiction in a time of increasing citizen journalism and social media commentary. That’s something I’ve blogged about in the past ( see  genuine enthusiasm shine through. I’m definitely more comfortable when interacting, either with other speakers or with questioners. That is, in part, why the Secrets of Subterranean London discussion worked so well. If you haven’t watched it, you can find a link

genuine enthusiasm shine through. I’m definitely more comfortable when interacting, either with other speakers or with questioners. That is, in part, why the Secrets of Subterranean London discussion worked so well. If you haven’t watched it, you can find a link  Fortunately, it worked out well.

Fortunately, it worked out well. Like any place inhabited by humans for centuries, London is a multi-layered city, its history piled up beneath the feet of the people who walk its streets. This was the subject of last night’s tremendous discussion with Dr Tom Ardill of the Museum of London and award-winning Blue Badge Guide Fiona Lukas.

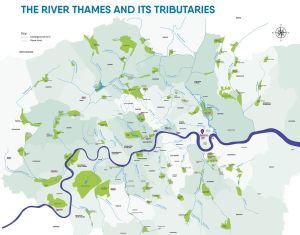

Like any place inhabited by humans for centuries, London is a multi-layered city, its history piled up beneath the feet of the people who walk its streets. This was the subject of last night’s tremendous discussion with Dr Tom Ardill of the Museum of London and award-winning Blue Badge Guide Fiona Lukas. that, by the thirteenth century Londoners of the City were seeking for a fresh water supply further afield and they lighted upon the Tyburn. In order to bring its waters to the City they constructed the Great Conduit which ran south then east across London.

that, by the thirteenth century Londoners of the City were seeking for a fresh water supply further afield and they lighted upon the Tyburn. In order to bring its waters to the City they constructed the Great Conduit which ran south then east across London. Fiona’s description of the modern travails of London Transport with new London Underground stations was very interesting, especially the example of the new, very deep and very modern, Westminster station . I never knew that the two District line tube tunnels were on top of one another not along side, but, when I thought about it, this made sense of the way the inside of the station was designed. I certainly wasn’t aware of the difficulties encountered because of the proximity of the station to the Houses of Parliament, not least the secrecy about why designs for the new station were repeatedly vetoed.

Fiona’s description of the modern travails of London Transport with new London Underground stations was very interesting, especially the example of the new, very deep and very modern, Westminster station . I never knew that the two District line tube tunnels were on top of one another not along side, but, when I thought about it, this made sense of the way the inside of the station was designed. I certainly wasn’t aware of the difficulties encountered because of the proximity of the station to the Houses of Parliament, not least the secrecy about why designs for the new station were repeatedly vetoed. where Churchill’s wartime cabinet used to meet when the Cabinet Office War Rooms were unavailable, or Brompton Road. There is also Aldwych, formerly Strand, a station I used to walk past every day on my way to work in Bush House, close to, yes, a bona fide Roman Baths.

where Churchill’s wartime cabinet used to meet when the Cabinet Office War Rooms were unavailable, or Brompton Road. There is also Aldwych, formerly Strand, a station I used to walk past every day on my way to work in Bush House, close to, yes, a bona fide Roman Baths. Claret Press is organising an online event which may be of interest to readers of this website. On 11th December, from 7 – 8 in the evening, I will be speaking with Tom Ardill, Curator at the Museum of London and Fiona Lukas, award-winning Blue Badge guide and expert on the London Underground.

Claret Press is organising an online event which may be of interest to readers of this website. On 11th December, from 7 – 8 in the evening, I will be speaking with Tom Ardill, Curator at the Museum of London and Fiona Lukas, award-winning Blue Badge guide and expert on the London Underground. the time. Did you know, for example, that there is a Tyburn Angling Society, set up to try and ‘restore’ the river so as to fish in it ( an almost impossible task since it has been subsumed into Bazalgette’s wonderful London sewer system, but a charming, if quixotic, idea )? He is also a fellow river traveller, having followed the course of the Tyburn, as I did, but taking the southernmost arm, down to Pimlico and he ran it, rather than walked. You can read about his run

the time. Did you know, for example, that there is a Tyburn Angling Society, set up to try and ‘restore’ the river so as to fish in it ( an almost impossible task since it has been subsumed into Bazalgette’s wonderful London sewer system, but a charming, if quixotic, idea )? He is also a fellow river traveller, having followed the course of the Tyburn, as I did, but taking the southernmost arm, down to Pimlico and he ran it, rather than walked. You can read about his run  The other contributor is Fiona Lukas, an award-winning Blue Badge Guide, ( she was Guide of the Year for the City of Westminster and City of London ) whose speciality is London Underground. She regularly hosts the popular tour The Lure of the Underground ( listen to her podcast about it

The other contributor is Fiona Lukas, an award-winning Blue Badge Guide, ( she was Guide of the Year for the City of Westminster and City of London ) whose speciality is London Underground. She regularly hosts the popular tour The Lure of the Underground ( listen to her podcast about it  the novel, although I expect Tom to have far more knowledge than I about the Tyburn itself. I’ll be touching on Plague Pits, Roman Remains – like the baths at North Audley Street, completely unmarked on the surface, the Great Conduit which runs along Oxford Street and, of course, the Palace of Westminster, with all its idiosyncrasies.

the novel, although I expect Tom to have far more knowledge than I about the Tyburn itself. I’ll be touching on Plague Pits, Roman Remains – like the baths at North Audley Street, completely unmarked on the surface, the Great Conduit which runs along Oxford Street and, of course, the Palace of Westminster, with all its idiosyncrasies. First up – bricks. The Victorians were great decorators in brick, something I’ve had several conversations about recently because we’ve just had a face lift for our Victorian house. I now know more about bricks than I ever thought was possible, largely courtesy of David Fairbrother, who oversaw the work, a man who truly loves bricks. On our walk we encountered some excellent examples of Victorian brickwork, like that announcing Grosvenor Works or the decoration on the buildings at the top of Great Smith Street, or, see left, the brickwork on the Marlborough Head public house, North Audley Street (readers of the novel will recognise that street name). The young woman working there was surprised and, I think, rather charmed, by our fruitless search

First up – bricks. The Victorians were great decorators in brick, something I’ve had several conversations about recently because we’ve just had a face lift for our Victorian house. I now know more about bricks than I ever thought was possible, largely courtesy of David Fairbrother, who oversaw the work, a man who truly loves bricks. On our walk we encountered some excellent examples of Victorian brickwork, like that announcing Grosvenor Works or the decoration on the buildings at the top of Great Smith Street, or, see left, the brickwork on the Marlborough Head public house, North Audley Street (readers of the novel will recognise that street name). The young woman working there was surprised and, I think, rather charmed, by our fruitless search  for any indicator that there were Roman baths nearby.

for any indicator that there were Roman baths nearby. broadly, around the subject matter of the book. So, a Stop Works sign propped in a doorway of the Norman Shaw buildings on the Embankment ( a former home of the Metropolitan Police and work place of one of the victims in the novel, where he is helping to refurbish the building ). Colourful chains at the construction site on Davies Street by Bond Street Underground Station, site of the first discovered crime, against said victim. The vaulted roof of the arches through which one passes from Horseguards Parade into Whitehall (which appears to be numbered, something I’ve not noticed before) and the receding arches within the arches, through which the protesters pass before harassing my heroine.

broadly, around the subject matter of the book. So, a Stop Works sign propped in a doorway of the Norman Shaw buildings on the Embankment ( a former home of the Metropolitan Police and work place of one of the victims in the novel, where he is helping to refurbish the building ). Colourful chains at the construction site on Davies Street by Bond Street Underground Station, site of the first discovered crime, against said victim. The vaulted roof of the arches through which one passes from Horseguards Parade into Whitehall (which appears to be numbered, something I’ve not noticed before) and the receding arches within the arches, through which the protesters pass before harassing my heroine. houses in London. Not, perhaps the smallest that, I believe, is The Dove in Hammersmith, but pretty small nonetheless. We found the four-storey Coach and Horses on the edge of Mayfair, it is still a working pub ( though we didn’t enter, either this or the Marlborough Head, just in case you’re wondering, we were committed book walkers ). Besides, the No Entry sign outside could have put us off. Other unusual architecture spotted includes Sothebys’ warehouse, found down a back street and what looked like a closed up market hall in Davies Mews.

houses in London. Not, perhaps the smallest that, I believe, is The Dove in Hammersmith, but pretty small nonetheless. We found the four-storey Coach and Horses on the edge of Mayfair, it is still a working pub ( though we didn’t enter, either this or the Marlborough Head, just in case you’re wondering, we were committed book walkers ). Besides, the No Entry sign outside could have put us off. Other unusual architecture spotted includes Sothebys’ warehouse, found down a back street and what looked like a closed up market hall in Davies Mews.